The EU AI Act has been published. Many manufacturers of medical devices and IVD, as well as other healthcare players, are faced with the major task of understanding the 140+ pages of legal text and complying with the requirements. Note: Infringements/violations of the AI Act are punishable by a fine of up to 7% of annual revenue.

This article saves research work and provides specific tips on how manufacturers (and other players) can most quickly achieve compliance.

Benefit from the free AI Act Starter Kit to quickly achieve conformity and impress in the next QM audit.

Medical device and IVD manufacturers without AI-based devices should read this article.

1. Whom the AI Act concerns (not only manufacturers!)

The EU AI Regulation 2024/1689 (in short, the AI Act) affects many players in the healthcare sector. The AI Act usually applies if the devices manufactured for or used there are or include an “AI system.” It also applies to manufacturers who use AI, for example LLMs, in the development of medical devices and in regulatory processes.

Unfortunately, the AI Act defines the term “AI system” very vaguely.

machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments;

AI Act, Article 3 (1)

A helpful simplification of the definition is equating AI systems with software systems or components that use machine learning (ML), i.e., that are or contain an “ML model,” in the sense of the AI Act.

The AI Act is one of many laws that manufacturers of AI-based medical devices must comply with. You can find an overview of the regulatory requirements for these AI-based devices here and an overview of the use of AI in healthcare here.

1.1 Provider/Manufacturer

1.1.1 Definitions

The mere fact that an IVD or a medical device uses machine learning does not necessarily mean that these devices and their manufacturers have to meet significant requirements of the AI Act (i.e., the requirements for high-risk systems).

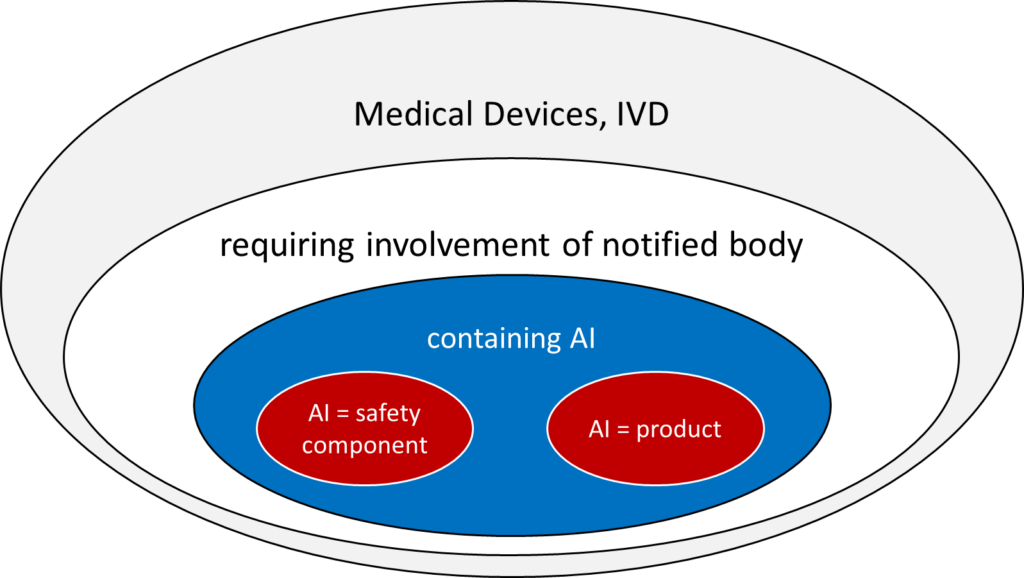

This is only the case if both conditions are met (see Fig. 1):

- The device (medical device or IVD) falls into a class for which a notified body must be involved in the conformity assessment procedure according to MDR or IVDR. These are the medical devices of classes I*, IIa, IIb, and III and IVD of classes As, B, C, and D.

- The AI (more precisely, the machine learning model) either is the product itself or serves as a “safety component” of a device.

The AI Act defines the term “safety component.”

a component of a product or of an AI system which fulfils a safety function for that product or AI system, or the failure or malfunctioning of which endangers the health and safety of persons or property;

AI Act, Article 3 (14)

Thus, a safety component can be both a part of standalone software and a part of a physical product.

Devices in the lowest class (e.g., MDR class I) that use machine learning fall under the AI Act but do not count as high-risk products. Therefore, they do not usually have to comply with any (tested) requirements that are relevant in practice.

1.1.2 Future addition

“Only certain AI systems are subject to regulatory obligations and oversight under the AI Act.” This is likely to be the favorite sentence of many in the draft of the guideline “on the definition of an artificial intelligence system established by Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (AI Act)”. This is because it clarifies that not all AI-based medical devices/IVD medical devices are covered by the AI Act.

However, this does not clarify what AI-based devices are or which are affected by the AI Act.

The authors struggle to provide clarification over 13 pages, and they do not always succeed. For example, at one point, they state that AI should be distinguished from “systems that are based on the rules defined solely by natural persons.” Elsewhere, they write that AI systems must pursue goals. These include “clearly stated goals that are directly encoded by the developer into the system.”

What is becoming clearer, at least, is that the definition of AI is not limited to machine learning but also includes other “reasoning” and “logical inference,” as is the case with “early generation expert systems.”

It is surprising that “operations such as sorting, searching, matching, chaining” can already be included. After all, what software does not perform these operations? On the other hand, the authors no longer consider logistic regression to be AI because it does not go beyond “basic data processing.”

There will only be a few medical devices that use machine learning (ML) and are not considered high-risk products. This is because AI/ML-based products always contain software or are standalone software. For such medical devices, rule 11 of the MDR applies. Unfortunately, this is now interpreted to mean that software as a medical device, in particular, must be classified as at least class IIa.

For IVD, the classification rules according to Annex VIII of the IVDR apply.

A practical simplification is to equate ML-based IVD and medical devices with high-risk products initially. Examples of exceptions to this rule are given in chapter 1.1.2.

1.1.3 Examples of high-risk and non-high-risk products

| Category: AI system is… | Example | Categorization |

| the medical device itself | AI-/ML-based standalone software designed to diagnose malignant skin lesions. (Depending on the software’s architecture and functionality, the AI system for the diagnosis only constitutes part of the device. This “diagnostic module” would then be considered a safety component.) | high-risk product |

| part of a safety component of the medical device | AI/ML-based dialysis machine software that controls ultrafiltration | high-risk product |

| part of a component of the device that is not a safety component | AI/ML-based software component that analyzes usage of the device to provide the manufacturer with indications regarding infringement/violation of license terms | non-high-risk product |

| a general-purpose AI (specifically, an LLM from one of the major providers, such as OpenAI) | LLM for writing software code that becomes part of a medical device | non-high-risk product |

1.1.4 The special case of “certain AI systems”

In Article 50, the AI Act introduces the term “certain AI systems” without defining it. IVD and medical devices may also be included (see Tab. 2).

| Device Characteristic | Example | Consequence |

| AI system is intended for direct interaction with natural persons | software for the diagnosis of malignant skin changes by a patient | The providers (manufacturers) must inform the persons about the use of the AI. |

| AI system is used for emotion recognition | software for use in psychotherapy | Deployers must inform the persons concerned about the use of the AI and the use of the data. |

This article will not discuss these “specific AI systems” any further, because the requirements are already largely covered by the MDR and IVDR.

1.2 Other actors

The AI Regulation places requirements on high-risk products (and thus IVD and medical devices) not only on the manufacturers but also on other actors:

- Deployers (e.g., hospitals, laboratories)

- Importers

- Distributors

The requirements for deployers are described in chapter 2.3 and more intensively in this article.

2. What requirements the AI Act imposes

2.1 Overview

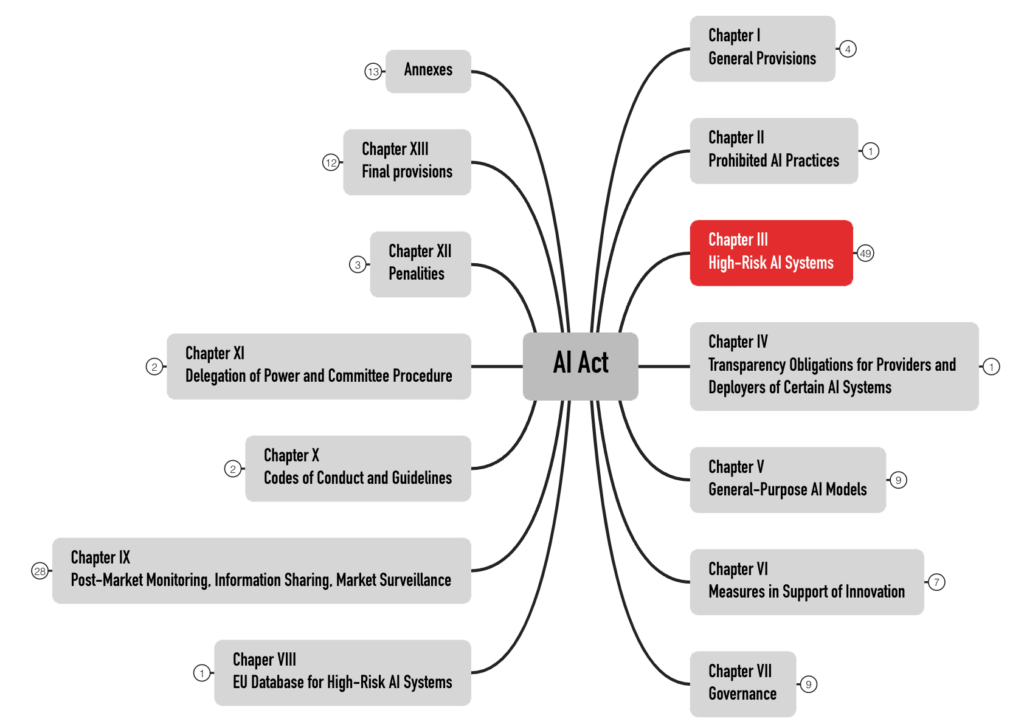

The AI Act formulates the requirements for high-risk products in Chapter III. With 49 articles, it is the most extensive chapter (see Fig. 2). This article does not address products in other risk categories.

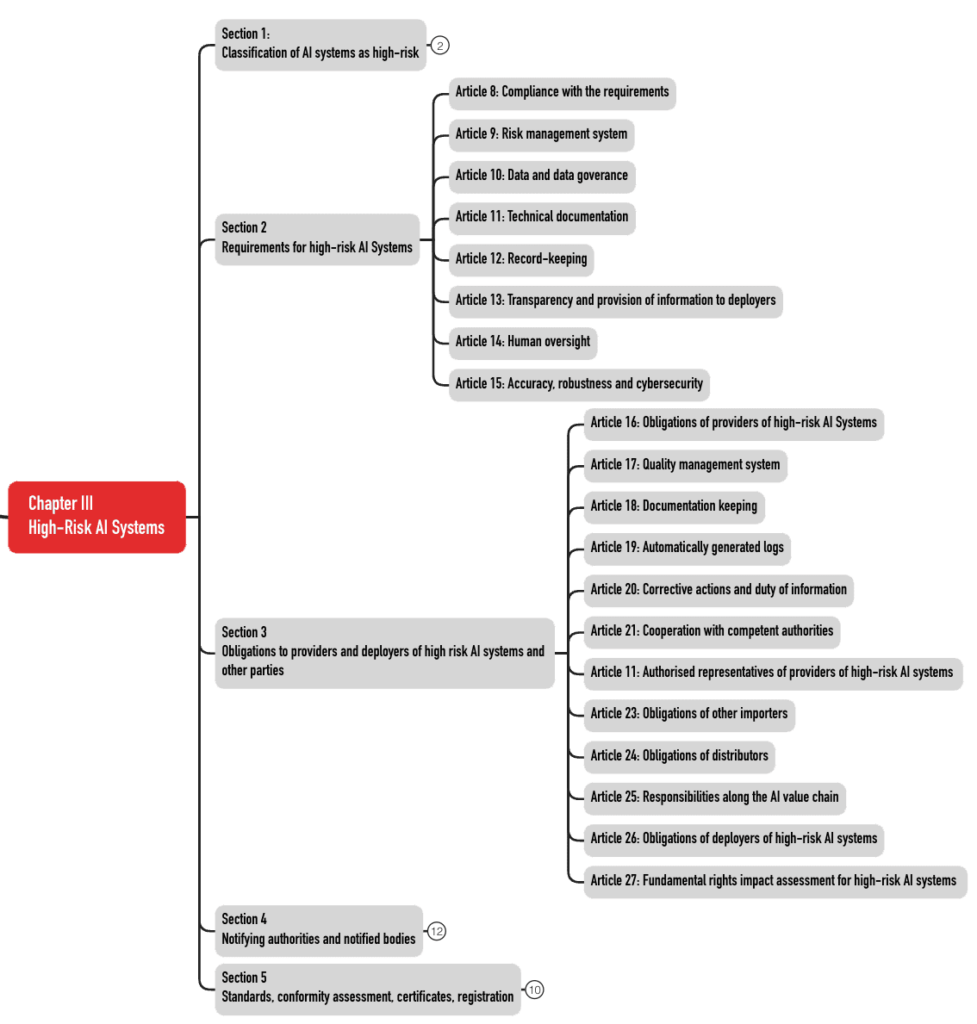

These 49 articles are divided into five sections (see Fig. 3). The requirements for the AI systems can be found in Sections 2 and 3.

Download the AI Act Starter Kit. It contains the complete mind maps in PDF and XMind format and further information.

2.2 Requirements for manufacturers

This section summarizes the main requirements of the AI Act for manufacturers.

| Requirement | Article | Comment |

| risk management system | 9 | The protection goals also affect fundamental rights. Testing is explicitly required. Concrete risks that manufacturers must consider are specified, e.g., “data poisoning” and cybersecurity problems. |

| data governance | 10 | instructions for handling training, validation, and test data |

| technical documentation (TD) | 11 | The TD can and should be combined with the TD of medical devices/IVD. |

| Record (logs) keeping obligations | 12 | This refers to a log, among others, of the use and input data, for example, in the sense of audit trails, in order to support post-market surveillance. |

| information | 13 | Electronic (!) instructions for use are required. |

| human supervision | 14 | Human oversight of system use should help to reduce risks. There are many links to the usability of these products. |

| accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity | 15 | These requirements not only concern the development of products but also organizational measures. Unlike some German notified bodies for medical devices, the AI Act does not exclude self-learning systems. |

| quality management system | 16, 17 | This system can and should be operated with the existing QMS. It requires additional/modified specification documents (see below). |

| conformity assessment procedure, declaration of conformity, and CE marking | 16, 43, 47, 48 | Notified bodies are to be involved (hopefully, these will be the same notified bodies as those for medical devices/IVD). |

| obligation to register in a database (not applicable for Annex-I-products such as medical devices and IVDs) | 16, 49 | comparable to EUDAMED |

| vigilance system, cooperation with authorities | 16, 20, 21 | comparable to the vigilance of MDR and IVDR |

| accessibility requirements | 16 | |

| appointment of an EU Authorized Representative | only if the manufacturer (“provider”) is not based in the EU |

2.3 Requirements for deployers

2.3.1 What a deployer is

The AI Regulation defines the term deployer:

a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity;

AI Act, Article 3 (4)

This means that a medical device manufacturer that uses LLMs (e.g., Microsoft Copilot) is considered an operator.

In contrast to the MDR and IVDR, the AI Act does not recognize the concept of in-house manufacturing or in-house IVD. However, if a health institution develops and puts an AI system into operation itself, the AI Act counts it as a provider. By definition, deployers who “put AI systems into service under their own name […]” are also considered providers.

a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that develops an AI system or a general-purpose AI model or that has an AI system or a general-purpose AI model developed and places it on the market or puts the AI system into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge;

AI Act, Article 3 (3)

For example, a hospital or medical laboratory that develops an AI system itself and puts it into service for diagnostic purposes, for example, counts as a provider.

The AI Act also explicitly applies to “product manufacturers placing on the market or putting into service an AI system together with their product and under their own name or trademark;” (Article 2(1)e)).

MDR and IVDR prohibit the in-house manufacture of products available on the market in a similar version, with CE marking, regardless of whether or not they contain an AI system.

However, transition periods apply to the requirements for in-house manufacture. For in-house IVD, Article 5(5)d of the IVDR does not apply until December 31, 2030.

2.3.2 What the obligations of the deployers are

The deployer’s obligations are formulated in the AI Act, in particular in Article 26.

| Obligation | Comment |

| ensure use as intended | Ensure that users have the necessary competencies and that they use the device in accordance with the instructions for use. This includes that the input data is sufficient for the intended purpose. The AI Act does not explain why this data should also be “representative.” Is it assumed that users train the system? |

| vigilance | If the deployers suspect the system is unsafe, they must inform the provider and (!) the market surveillance authorities. |

| keep records | The AI systems must generate logs (e.g., audit logs) for post-market surveillance. The deployers must keep these. The authors of the AI Act are aware that they may conflict with data protection in doing so. |

| inform about deployment | Deployers must inform employees and their representatives (e.g., works council). |

| ensure data protection | The AI Act requires deployers to fulfill their obligations under the GDPR. |

Find more details on AI Act requirements for deployers in this article.

3. When the requirements come into force

The effective dates and dates of entry into force are defined in Article 113.

| Date | Action |

| July 12, 2024 | EU passes AI Regulation |

| August 1, 2024 | AI Regulation enters into force |

| February 2, 2025 | prohibition of “prohibited practices” becomes effective |

| August 2, 2025 | regulations for general-purpose AI models take effect (if these are placed on the market from now on) |

| August 2, 2026 | the AI Regulation applies widely, including to many high-risk products |

| August 2, 2027 | However, products according to Article 6(1) (these are IVD and medical devices as well as safety components) are only now considered high-risk products. This will likely be the most important deadline for IVD and medical device manufacturers. |

| August 2, 2027 | The provisions for AI models for general use will become effective if these were placed on the market before August 1, 2025. |

4. What manufacturers should do now

The development of IVD and medical devices usually takes years. Therefore, manufacturers are well advised to start dealing with the requirements of the AI Act immediately and not wait until the end of the transition period.

In addition, during audits, notified bodies specifically check whether manufacturers systematically identify changes to regulatory requirements and take the necessary measures. The AI Regulation is an example of such a regulatory change.

4.1 Build competence

The hope that good data scientists within the company are sufficient for compliance with the legal requirements for competence is unlikely to be fulfilled. More comprehensive knowledge is necessary, for example, in these activities and areas:

- Validation of the systems for collecting and processing (pre-processing) the training, validation, and test data

- Risk management, which must include new goals and new risks

- Implementation of relevant (harmonized) standards that will be published in the future

- Test methods for AI models

- Methods for the interpretability (= explainability + transparency) of these models

- Data protection for AI models (especially for training, validation, and test data sets and for the protocols)

ISO 13485 even requires the “organizations” to define the competencies specifically for each development project/product.

Article 4 of the AI Act requires competence to be ensured “to their best extent.” It does not specify which competencies are meant. The EU’s AI Act does not exclude deployers and users from its requirements.

The Johner Institute AI guideline, also used by the notified bodies, contains important checklists. You can use these to check and establish the conformity of your AI-based medical devices.

4.2 Expand QM specifications

Manufacturers should adapt and supplement their specification documents, such as standard operating procedures, checklists, and templates, to ensure compliance with the additional requirements of the AI Regulation.

These specification documents must be continuously reviewed to ensure that they correspond to the state of the art (in particular harmonized standards) and that training is provided.

4.3 Choose and manage external partners

The AI Act not only affects the way companies work internally but also how they interact with external parties. This applies, for example, to the following activities:

- Identify, qualify, and continuously evaluate suppliers (e.g., open-source models, development service providers, notified bodies)

- Select, instruct, and verify distributors

- Select EU Authorized Representatives if necessary

- Select partners for training and consulting (Tip: Johner Institute 🙂)

- Find AI real-world laboratories

- Research funding programs, apply for research grants

5. Background, criticism, news

a) Background

On its webpage New rules for Artificial Intelligence – Questions and Answers the EU announces its intention to regulate AI in all sectors on a risk-based basis and to monitor compliance with the regulations.

The EU sees the opportunities of using AI but also its risks. It explicitly mentions healthcare and wants to prevent fragmentation of the single market through EU-wide regulation.

Regulation should affect both manufacturers and users. The regulations to be implemented depend on whether the AI system is classified as a high-risk AI system or not. Devices covered by the MDR or IVDR that require the involvement of a notified body are considered high-risk.

One focus of regulation will be on remote biometric identification.

The regulation also provides for monitoring and auditing; in addition, it extends to imported devices. The EU plans for this regulation to interact with the new Machinery Regulation, which would replace the current Machinery Directive.

A special committee is to be established: “The European Committee on Artificial Intelligence is to be composed of high-level representatives of the competent national supervisory authorities, the European Data Protection Supervisor, and the Commission.”

b) Criticism

As always, the EU emphasizes that the location should be promoted, and SMEs should not be unduly burdened. These statements can also be found in the MDR. But none of the regulations seem to meet this requirement.

Criticism of definitions

The definition is unclear. Artificial Intelligence procedures include not only machine learning but also:

“- Logic and knowledge-based approaches, including knowledge representation, inductive (logic) programming, knowledge bases, inference and deduction engines, (symbolic) reasoning and expert systems; – Statistical approaches, Bayesian estimation, search, and optimization methods.”

This broad scope may result in many medical devices containing software falling within the scope of the AI Regulation. Accordingly, any decision tree cast in software would be an AI system.

The regulation does define the term “safety component,” but it uses the undefined term “safety function” for it.

component of a device or system that performs a safety function for that device or system, or whose failure or malfunction endangers the health and safety of persons or property;

AI Act, Article 3 (14)

The AI Regulation also does not define other terms in accordance with the MDR, e.g., “post-market monitoring” or “serious incident.”

Criticism of the scope

The AI Regulation explicitly addresses medical devices and IVD. There is a duplication of requirements. MDR and IVDR already require cybersecurity, risk management, post-market surveillance, a notification system, technical documentation, a QM system, etc. Manufacturers will soon have to demonstrate compliance with two regulations!

Criticism of the risk-based approach

The regulation applies regardless of what the AI is used for in the medical device. A hazard to health, regardless of the level of risk, makes the device a high-risk device.

Even an AI that is intended to realize the lower-wear operation of an engine would fall under EU regulation. As a consequence, manufacturers will think twice before making use of AI procedures. This can have a negative impact on innovation but also on the safety and performance of devices. This is because, as a rule, manufacturers use AI to improve the safety, performance, and effectiveness of devices. Otherwise, they would not be allowed to use AI at all.

This requirement rules out the use of AI in situations in which humans can no longer react quickly enough. Yet, it is precisely in these situations that the use of AI could be particularly helpful.

If we have to place a person next to each device to “effectively supervise” the use of AI, this will mean the end of most AI-based products.

Criticism of the classification

The unfortunate Rule 11 classifies software – regardless of risk – into class IIa or higher in the vast majority of cases. This means that medical devices are subject to the extensive requirements for high-risk products. The negative effects of Rule 11 are reinforced by the AI Regulation.

Criticism of the requirements’ closeness to reality

In Article 10, the AI Regulation requires:

“training, validation, and testing data sets shall be relevant, representative, free of errors and complete.“

Real-world data is rarely error-free and complete. It also remains unclear what is meant by “complete.” Do all data sets have to be present (whatever that means) or all data of a data set?

Criticism of the overreach of the regulation

The annex to the AI Regulation requires manufacturers to provide authorities with full remote access to training, validation, and test data, even through an API:

The technical documentation shall be examined by the notified body. Where relevant, and limited to what is necessary to fulfil its tasks, the notified body shall be granted full access to the training, validation, and testing data sets used, including, where appropriate and subject to security safeguards, through API or other relevant technical means and tools enabling remote access.

Making confidential patient data accessible via remote access is in dispute with the legal requirement of data protection by design. Health data belongs to the personal data category that requires special protection.

Developing and providing an external API to the training data means an additional effort for the manufacturers.

That authorities with this access can download, analyze, and evaluate the data or AI with reasonable effort and time is unrealistic.

For other, often even more critical data and information on product design and production (e.g., source code or CAD drawings), no one would seriously require manufacturers to provide remote access to authorities.

c) Current status

As of October 2025, no organizations have yet been designated for the AI Act. This means that there are still no notified bodies for the AI Act. However, it is expected that all notified bodies for the MDR and IVDR will also become responsible for the AI Act through a scope extension.

Furthermore, the ZLG is to remain the “competent authority” for medical devices and IVDs (also for the AI Act) and not, for example, the Federal Network Agency.

Accreditation for the ISO 42001 standard is independent of this (by the DAkkS). This standard is currently not harmonized for the MDR, IVDR, or AI Act.

6. Summary and conclusion

The AI Act is here to stay. The broad, sometimes scathing criticism of this EU AI Regulation, which we summarize elsewhere, does nothing to change this.

a) Start now, but risk-based

Therefore, manufacturers must familiarize themselves with the regulation. Tip: Start soon because it is difficult to comply with some requirements for a device that has already been developed.

Manufacturers should proceed in a risk-based manner:

- As with the MDR and IVDR, it helps to start early to minimize risks in audits and for the planned (“time & budget”) development and marketing of devices.

- On the other hand, manufacturers must be aware that the standards for the AI Act have yet to be written and harmonized. This may require the QM documents to be revised.

But the date by which medical devices and IVD must comply with the requirements for high-risk products has been set, regardless of (slow) standard harmonization.

b) Initiate a change project

The AI Act means more than “just another law.” It affects many departments:

- Research and development, including usability engineering and data science

- Quality management, including supplier management

- Regulatory affairs, including vigilance and selection of (new?) notified bodies

- Data protection and IT security

- Risk management

- Product management and customer support

These changes require resources (money, trained personnel) and cross-departmental planning. Therefore, the executives in charge should set up a change project and not just assign regulatory affairs with a “your job.”

The AI Act Starter Kit provides an initial overview of the tasks ahead.

The experts at the Johner Institute help manufacturers in the areas of AI, QM, and RA to comply with the requirements of the AI Act step by step with a lean project.

Change history:

- 2025-10-21:

- In Chapter 5.b), subheading “Criticism of the excessive scope of the regulation,” the reference to Annex IV and the corresponding quote have been added. In the draft AI Act, this requirement was included in Article 64.

- Clarified in Chapter 2.2 that the registration requirements do not apply to medical device manufacturers.

- 2025-10-15: Several changes

- Notes on scope added to the first paragraph in section 1

- Example added to section 1.1.3

- Example added to 2.3.1 after the definition box

- Chapter 5.c) (“Current”) added

- 2025-04-15: Note added at the beginning of the article for manufacturers without AI-based devices

- 2025-02-22: New chapter 5 (taken from article on machine learning, restructured and updated), section 1.1.2 inserted, the following numbering adjusted

- 2025-10-22: First version of the article published

Great article! We always appreciate valuable insights like these. Thanks for sharing!