The FDA sets clear requirements for human factors engineering (HFE) and usability engineering of medical devices.

- But which devices are subject to these requirements?

- Which regulatory documents do you need to be familiar with?

- And how do you implement the FDA’s human factors engineering requirements in practice?

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the FDA’s usability requirements and shows you how to successfully implement them in your product development.

1. Introduction

1.1 When do you need to comply with FDA human factors requirements?

The FDA requirements for human factors engineering do not apply uniformly to all medical devices. The requirements depend on various factors:

1.1.1 Product classification and software

Generally, all devices must demonstrate compliance with usability requirements, i.e., a usability engineering file (UEF) or human factors engineering report (HFE report) must always be available. However, this does not imply that a human factors evaluation (i.e., studies) is also necessary.

The statement that the UEF is not necessary for class I devices is therefore incorrect. Instead, the UEF would justify the low risk that no human factors validation (summative evaluation) is necessary.

The FDA derives the HFE requirements from the Quality System Regulation (QSR), in particular from:

- Design Input: “Address the intended use of the device, including the needs of the user and patient.”

- Design Validation: “Ensure that devices conform to defined user needs and intended uses.”

1.1.2 Risk due to use errors

The FDA explicitly requires human factors engineering if the risk analysis shows that use errors can lead to serious harm.

Serious Harm: The FDA defines this as death, serious injury, or serious adverse events that may result from the use or misuse of the medical device. (“Includes both serious injury and death”)

Serious Injury: An injury or illness that is life-threatening, results in permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure, or necessitates medical or surgical intervention to preclude permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure. Permanent means irreversible impairment or damage to a body structure or function, excluding trivial impairment or damage.

In this case, human factors data must be submitted in the premarket submission (PMA, 510(k)).

1.1.3 Specific product categories

HFE is mandatory for certain high-risk devices. The FDA has published a list of devices for which it considers human factors to be particularly critical:

- ventilators

- dialysis machines

- infusion pumps

- defibrillators

- blood glucose meters

- and other devices

The complete list can be found in the FDA guidance document “List of Highest Priority Devices for Human Factors Review”.

Note: This document is replaced by the new guidance “Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions”, which is still in draft form.

1.1.4 FDA discretion

The authority may also request HFE data in the following situations:

- in case of product changes

- after problems have been reported

- in certain approval procedures (especially PMA)

- in case of a change in the user group

If you are unsure, the FDA recommends a pre-submission (Q-submission) to clarify in advance which HFE activities are required for your specific device. This can save time and money in the later approval process.

1.2 Regulatory framework: You need to be familiar with these documents

The FDA requirements for human factors are based on a comprehensive regulatory framework:

1.2.1 Binding regulations

- 21 CFR part 820.30 (Design Controls): defines basic requirements for design input and design validation

- Quality System Regulation (QSR): overarching quality system requirements

21 CFR part 820, in particular part 820.30, will be replaced by ISO 13485 as part of the transition to the Quality Management System Regulation.

1.2.2 Recognized standards

- IEC 62366-1:2015: International Standard for Usability Engineering Process

- AAMI/ANSI HE75:2009: Human Factors Engineering – Design of Medical Devices

- ISO 14971:2007: Risk Management

The new draft guidance “Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions” refers to “ANSI/AAMI/ISO 14971:2019 Medical devices—Application of risk management to medical devices.” You should take this into account in your documentation and, if necessary, document any differences from the current version.

1.2.3 FDA guidance documents

The FDA has published two key guidance documents on human factors engineering:

1. Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical Devices (February 2016)

- describes the HFE process

- defines methods and activities

- specifies validation requirements

2. Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions (December 2022, Draft)

- specifies documents to be submitted

- introduces risk-based categorization

- replaces previous prioritization lists

The second document supplements and clarifies the first. It specifically replaces Chapters 3 (Definitions), 9 (Documentation), and Annex A (HFE/UE Report) of the first document. Both documents must therefore be considered together.

1.3 Human Factors vs. Usability Engineering: Disambiguation

The FDA defines HFE as “Application of knowledge about human behavior, abilities, limitations, and other characteristics to the design of medical devices (including software), systems and tasks to achieve adequate usability.“

The FDA uses the terms human factors engineering and usability engineering largely synonymously:

- Human Factors Engineering (HFE): traditional FDA term, emphasizes safety aspects

- Usability Engineering: internationally accepted term (IEC 62366-1)

You can use both terms in your documentation. It is important that you remain consistent and make it clear when you first use them that you are using the terms synonymously.

Key point: Both approaches primarily focus on minimizing risk through usability engineering, rather than market appeal or customer satisfaction.

2. The HFE process according to the FDA

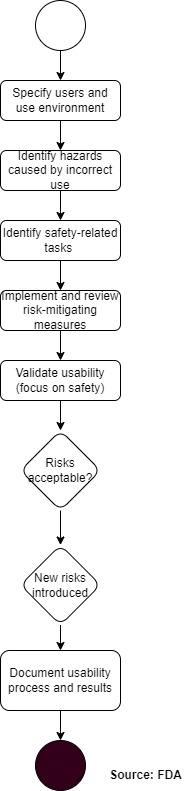

FDA describes a systematic process for human factors engineering that is strongly oriented toward risk management. This process ensures that use errors and resulting risks are identified and minimized at an early stage.

2.1 Overview of the HFE process

The FDA’s human factors engineering process has an iterative consequence that runs parallel to product development. It is based on established risk management in accordance with ISO 14971 but focuses specifically on use-related risks. In contrast to IEC 62366-1, the FDA describes the specific activities and methods rather than the process itself.

The four main phases of the process are:

- User research (users, use environment, and user interface)

- Risk analysis and identification of critical tasks

- Formative evaluation during development & risk minimization

- Usability validation/human factors validation testing

2.2 Phase 1: User research

The FDA requires that all relevant characteristics of users, context of use, and the user interface be systematically recorded and documented.

- Users: All intended user groups must be considered, including professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses), technical personnel (e.g., for maintenance, installation, and cleaning), as well as laypersons, patients, and their relatives. Decisive factors here include characteristics such as physical and sensory abilities, cognitive requirements, level of experience, language and reading skills, motivation, and level of training.

- Context of use: The analysis covers all locations where the device is used (e.g., hospital, operating room, home environment, emergency use) and the conditions there. Typical influencing factors include light and noise conditions, spatial conditions, possible distractions, or emergencies.

- User interface: All elements of interaction must be considered and described, from physical device design and controls to displays, alarms, and software interfaces to instructions for use and training. It is crucial that the operating logic meets the expectations and abilities of the users and that errors are actively prevented.

Use methods such as interviews, observations, and focus groups to gain a realistic understanding of users and their work environment. This is the only way to identify and address use-related risks at an early stage.

Taking users, context of use, and the user interface into account forms the basis for a usable and safe medical device design. The analysis of users and use environments is a common thread running through the entire risk analysis: it forms the basis for identifying critical tasks. It must be closely linked to the risk analysis. That is the only way to ensure that the relevant user groups can be defined for each critical task. This is essential in order to select the right test subjects for subsequent human factors validation based on the critical tasks.

Careful documentation of user research is not only essential for subsequent risk analysis and validation but is also explicitly required by the FDA in the submission. The variability and potential limitations of all user groups as well as the real environmental conditions must be taken into account throughout the entire development process.

2.3 Phase 2: Risk analysis and identification of critical tasks

2.3.1 Focus on safety-related tasks

The FDA first requires the identification of all safety-related tasks on the system. This task-oriented approach is consistent with the concept of IEC 62366-1.

The FDA defines a critical task as “A user task which, if performed incorrectly or not performed at all, would or could cause serious harm to the patient or user, where harm is defined to include compromised medical care,” in which an application error could lead to serious damage.

2.3.2 Methods for risk analysis

The FDA lists specific methods for identifying and analyzing use risks:

- FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis): systematic analysis of possible failures and their effects

- FTA (Fault Tree Analysis): top-down analysis of adverse events

- Task Analysis: breaking down work processes into individual steps

- Expert Review: evaluation by human factors specialists

- Context Analysis: examination of the real use environment

- Interviews and Focus Groups: direct questioning of users

Combine several methods for a comprehensive risk analysis. The FDA particularly recommends task analysis as a basis, supplemented by FMEA for systematic error analysis.

2.3.3 Sources of information to be considered

The FDA explicitly requires the following sources to be included in the risk analysis:

- Feedback from customers and users

- Reports from service, sales personnel, and trainers

- Results of previous HFE studies (including from predecessor devices)

- Scientific publications and specialist articles

- Reporting to the authorities (FDA MAUDE database, BfArM database, etc.)

The MAUDE database of the FDA (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) contains reports on adverse events involving medical devices and is publicly accessible. It is a valuable source for identifying known use problems.

2.4 Phase 3: Formative evaluation & risk minimization

2.4.1 Objectives of formative evaluation

The FDA requires formative evaluations during development with the following objectives:

- Generate ideas for test scenarios for later validation

- Identify dangerous situations at an early stage

- Gather input for improvements to the user interface

- Develop a better understanding of possible application errors

The explicit requirement for formative evaluations during the design process goes beyond the requirements of IEC 62366-1. The FDA expects you to document these activities and summarize them in your submission.

2.4.2 Methods of formative evaluation

The FDA mentions two main methods:

- performance with representative users (not only experts)

- systematic review of tasks

- identification of comprehension problems and sources of error

Simulated Use Testing

- tests with prototypes or mockups

- simulation of realistic use scenarios

- observation and questioning of test subjects

Start with simple paper prototypes or mock-ups. The FDA explicitly allows testing on non-final versions. This enables you to gain insights early on at a low cost.

2.4.3 Risk control measures

The manufacturer must minimize any (unacceptable) risks identified during the formative evaluation. The FDA follows the established hierarchy of risk control:

- Inherently safe design: elimination or reduction of risks through the design itself

- Protective measures: alarms, warnings, safety mechanisms in the product or in production

- Instructions for use: instructions for use, labels, training

The FDA only accepts risk minimization through information in the instructions for use if you can prove its effectiveness. The same applies to “additional training.”

Specific examples of design measures:

- simplification of workflows

- clear label and marking

- error-tolerant design (e.g., undo functions)

- physical barriers against incorrect operation

- consistent user guidance

2.5 Phase 4: Human factors validation testing

2.5.1 Validation requirements

The FDA sets specific requirements for human factors validation:

Practical definition: The summative assessment of usability with the final device under realistic conditions. IEC 62366-1 refers to this as summative evaluation.

Official definition of the FDA: Testing conducted at the end of the device development process to assess user interactions with a device user interface to identify use errors that would or could result in serious harm to the patient or user. Human factors validation testing is also used to assess the effectiveness of risk management measures. Human factors validation testing represents one portion of design validation.

Key requirements:

- All critical tasks must be validated.

- Testing with predefined success criteria

- Proof that no serious usage problems occur

- Collection of objective data (observation) and subjective data (survey)

- Review of effectiveness (“For the device to be considered to be optimized with respect to use safety and effectiveness”).

2.5.2 Test conditions and participants

Device

- testing with the final product

- including final labeling (instructions for use, labels)

- in the final configuration

Participants

- representative users from all relevant user groups

- no employees of the manufacturer

- at least 15 participants per user group

- Users must be from the US: Professional users must work within the US healthcare system, so the evaluation typically takes place in the US. It is not sufficient to recruit US citizens in Germany who are not (or no longer) active in the US healthcare system. The cultural background of lay persons should also be taken into account.

Plan ahead for recruiting US users. The Johner Institute can assist you with recruiting test subjects and with the organization and performance of usability tests with US users.

Test environment:

- representative use environment

- realistic conditions (light, noise, distractions)

- training of participants in accordance with the real scenario

2.5.3 Validation documentation

The validation must be comprehensively documented:

- test protocol with all tasks

- success criteria and their justification

- observation protocols

- evaluation of all use problems

- assessment of residual risks

- justification of why remaining problems are acceptable

The FDA expects a detailed discussion of all observed use problems, even if they did not lead to errors. That helps the authority evaluate the thoroughness of your evaluation.

3. FDA human factors submission requirements

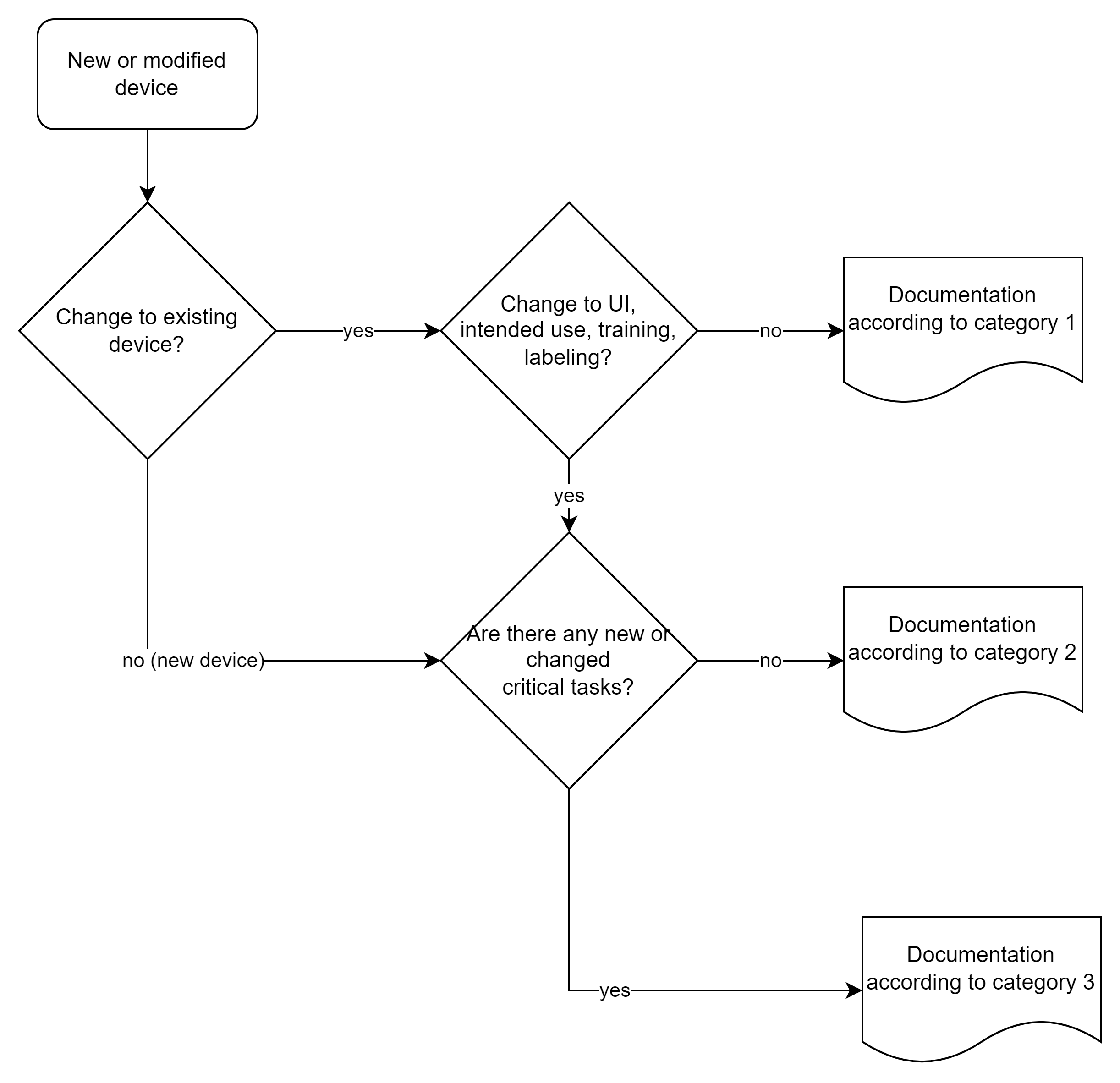

In December 2022, the FDA issued clear guidelines in its draft guidance Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions on which human factors documents must be submitted for approval. The scope depends on the risk associated with the device.

3.1 The three documentation categories

The FDA distinguishes between three categories of human factors documentation based on the risk of the device or product change:

This categorization replaces the previous “List of Highest Priority Devices for Human Factors Review”. The new risk-based approach allows for a more differentiated view and can reduce the documentation effort for low-risk devices.

3.2 Scope of documents to be submitted

3.2.1 Overview of requirements by category

| Documents | Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 |

| HF summary | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Description of the intended purpose | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Description of the user interface | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Known use problems | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Formative evaluations | – | – | ✓ |

| Risk analysis (HF focus) | – | – | ✓ |

| Validation details | – | – | ✓ |

3.2.2 Category 1: HF summary

For category 1, a brief summary and an explanation that there were no changes to the UI, intended purpose, training, or labeling, or that it was a software bug fix in the backend, is sufficient.

3.2.3 Category 2: Moderate documentation

In addition to the summary, the following must be submitted:

Description of the intended purpose:

- Intended users (user groups and their characteristics)

- Intended use environment

- Training requirements

Description of the user interface:

- Overview of the user interface

- Main functions and operating concept

- Screenshots or photos of the most important screens/controls

Summary of known use problems:

This information may also come from:

- Post-market data from predecessor devices

- Literature research on similar devices

- Findings from customer complaints

It is important that the risk analysis shows that the changes do not affect critical tasks or create new ones. This statement should be included in the categorization.

3.2.4 Category 3: Complete HF documentation

For high-risk devices, the FDA requires the complete HF portfolio, i.e., in addition to the documents already mentioned:

Summary of formative evaluations:

- Formative tests performed

- Key findings

- Resulting design changes

Risk analysis with HF focus:

- Use-related risk analysis (URRA)

- Identification and description of critical tasks

- Risk control measures

“Systematic use of available information to identify use related hazards and to estimate the use-related risk“

Abnormal use (intentional misuse) is out of scope, but may be part of foreseeable misuse.

Details of RF validation:

- complete test protocol

- participant demographics

- test results for all critical tasks

- analysis and evaluation of all usability issues

- discussion of residual risks

3.3 Structure of the HFE report

3.3.1 Recommended structure according to FDA

The FDA recommends the following structure for the human factors engineering report:

1. Conclusion and high-level summary

- Statement that the device is safe

- Summary of the results, in particular the risks

- Activities carried out

2. Description of users, use environment, and training

- Summary of the intended purpose

- User profiles

- Use environment with critical factors

- Training concept and materials

3. Description of the user interface

- Graphical representation, e.g., photos, drawings of the device

- Description of user interaction with the device (e.g., sequences of activities)

- Accompanying information

- Description of changes, if applicable

4. Summary of known use problems

- Scope: predecessor device, similar device

- Relevance for the current device

- If possible: statement that no use problems are known

5. Description of the analysis, e.g., formative evaluation

- Method description

- Important results

- Subsequent design decisions

6. Risk analysis

- Possible use errors

- Hazards

- Risks and possible harm

7. Description of critical tasks

- Detailed task descriptions

- Related use scenarios

- Changes to the user interface

8. Details of HF validation

- Study design and methodology

- Implementation

- Results

- Discussion and conclusions

Use this structure as a template for your report. FDA reviewers expect this outline and can thus efficiently find the information they need.

3.3.2 Special documentation requirements

Clarity regarding critical tasks: The FDA requires a clear statement regarding the presence or absence of critical tasks. If none have been identified, this must be clearly justified.

Residual risk assessment: Any remaining usage risk must be discussed and evaluated:

- Why can’t the risk be further reduced?

- Why is the risk acceptable?

- What post-market measures are planned?

The Johner Institute provides an annotated version of the FDA document Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions, which contains practical advice on implementation.

Traceability: The documentation should be designed in such a way that an FDA reviewer can understand without further inquiry

- why certain design decisions were made,

- how risks were identified and controlled,

- why the final design is safe and effective.

Avoid spreading information across multiple documents. The FDA prefers a consolidated HF report that contains all relevant information. References to other documents should be minimized.

4. Practical implementation

Successful implementation of FDA requirements requires a structured process that complies with both FDA and IEC 62366-1. This chapter shows you how to implement the requirements in practice.

4.1 An integrated HFE process

4.1.1 Process proposal for FDA and IEC-compliant development

The following process is compliant with both FDA and IEC 62366-1 requirements.

This process integrates the FDA phases (user research, risk analysis, formative evaluation, validation) with the usability engineering process of IEC 62366-1. This allows you to avoid duplication of work and achieve compliance with both regulations simultaneously.

4.1.2 Key activities in the development process

Early development phase:

- User research and context analysis

- Initial risk analysis (use-related risk analysis)

- Definition of user groups and use environment

Concept phase:

- Identification of critical tasks

- Initial formative evaluations (e.g., with paper prototypes)

- Iterative design improvements

Detailed development:

- Further formative tests with functional prototypes

- Refinement of risk analysis

- Finalization of risk control measures

Verification and validation:

- Summative evaluation/HF validation testing

- Assessment of residual risks

- Finalization of HF documentation

Do not start HF activities shortly before approval. The FDA expects evidence of formative evaluations throughout the entire development process. Late changes are expensive and delay market launch.

4.2 Integration of FDA and IEC 62366-1 requirements

4.2.1 Terminology mapping

The different terminology can be confusing. Table 1 compares the most important equivalents:

| Term of the FDA | Term in IEC 62366-1 | Explanation |

| Human Factors Engineering | Usability Engineering | entire process |

| Critical Task | Hazard-Related Use Scenario | The safety-critical task does not entirely correspond to the safety-related use scenario. Rather, the latter includes the “critical task.” |

| HF Validation Testing | Summative Evaluation | final validation |

| Use Error | Use Error | use error (see note) |

| Formative Evaluation | Formative Evaluation | evaluation during development |

The FDA defines Use Error as “User action or lack of action that was different from that expcted by the manufacturer and caused a result that (1) was different from the result exptected by the user and (2) was not caused solely by device failure and (3) did or could result in harm.“

Without potential harm, a use error is therefore not a use error from the FDA’s perspective.

4.2.2 Documentation synergy

A smart approach to documentation:

One document – two regulations

- Create an HF/usability engineering file.

- Structure according to IEC 62366-1 requirements.

- Add FDA-specific elements.

- Use this to create the FDA HF report.

IEC 62366-1 requires a usability engineering file with specific content. This largely overlaps with FDA requirements. Clever structuring saves a considerable amount of documentation effort.

4.3 Particularities and practical tips

1. Plan for US users early on

- FDA requires testing with US users.

- Recruitment can be time-consuming.

- Be aware of cultural differences.

2. Use pre-submission

- Submit Q-submission if you are unsure.

- FDA provides binding information on HF requirements.

- Avoids expensive surprises

3. Realistic test conditions

- Authentically replicate the use environment.

- Include typical disruptive factors.

- Realistic training of test users

Document close calls (i.e., near misses) and minor problems in the validation process. The FDA values transparency and sees it as evidence of thorough testing.

4.4 Available resources and support

4.4.1 FDA ressources

Guidance Documents

- Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical Devices

- Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions

Data Bases

- MAUDE database for reported use problems

- FDA website with device-specific guidance

FDA Contact

- Q-Submission Program for pre-submissions

- Division of Human Factors in CDRH

4.4.2 Practical working aids

Templates: The Johner Institute offers various resources:

- Templates for the HF report

- Protocol templates for validation tests

- Annotated FDA documents

In Auditgarant, you will find complete document templates ranging from use scenarios and usability validation plans to HF reports. These have already been optimized for FDA conformity.

4.4.3 External support

When external help is useful:

- If you lack experience with FDA submissions

- If you need US users for testing

- If internal resources are scarce

- For complex or novel devices

The Johner Institute offers comprehensive usability services, including:

- Conducting usability tests with US users

- Reviewing HF documentation

- Support with Q-Submissions

- Training on FDA human factors

Investing in professional support often pays off. Delayed or rejected FDA clearance usually costs more than external consulting.

5. Summary and conclusion

The FDA requirements for human factors engineering are comprehensive, but well-structured and understandable. With the proper understanding and a systematic approach, compliance with these requirements can be achieved efficiently.

5.1 The key findings at a glance

5.1.1 Regulatory clarity

The FDA has established clear guidelines in its two guidance documents:

- The HFE process is defined in the guidance document “Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical Devices.”

- The documents to be submitted are specified in the guidance document “Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions.”

- The risk-based approach enables an appropriate level of documentation.

5.1.2 Focus on patient safety

The FDA philosophy is clear:

- Primary objective: Minimizing risks due to use errors

- Secondary: User-friendliness and market success

- Core principle: Risk-based approach to all decisions

This prioritization distinguishes medical human factors from commercial UX design.

5.2 Success factors for FDA clearance

5.2.1 Strategic success factors

1. Early start: Human factors engineering is not an “add-on” at the end of development, but an integral part of the design process.

2. Risk-based thinking: Focus your resources on critical tasks. The FDA values focused work more than extensive but superficial documentation.

3. Transparency and completeness: Document problems and their solutions. The FDA values an open approach to challenges.

Well-structured and complete HF documentation can shorten the FDA review process by weeks. Invest in quality rather than quantity.

5.2.2 Operational success factors

Use FDA resources:

- Q-Submission for binding preliminary clarifications

- MAUDE database for known issues

- Guidance documents as concrete instructions

Plan for US-specific requirements:

- US users for validation

- Consider the US use environment

- Take cultural differences into account

Document throughout the process:

- Don’t wait until the end to write everything down

- Document formative evaluations in a timely manner

- Record design decisions with justification

5.3 Common mistakes and how to avoid them

5.3.1 The top 5 mistakes in FDA HF submissions

1. Human factors engineering too late

- Mistake: HF only shortly before approval

- Solution: Integration from the start of the project

2. Lack of US users during validation

- Mistake: Tests only with European users

- Solution: Early planning of US tests

3. Incomplete risk analysis

- Error: Focus only on obvious risks

- Solution: Systematic analysis of all tasks

4. Training as the only risk control

- Error: “We’ll train them out of it.”

- Solution: Prioritize design-based measures

5. Lack of formative evaluations

- Error: Only final validation

- Solution: Iterative testing during development

These errors regularly lead to significant delays or even rejection of FDA submissions. The correction afterwards is always more costly than doing it right from the start.

5.4 Outlook and recommendations

For manufacturers who want to implement FDA-compliant human factors:

1. Status quo

- What HF activities are you already carrying out?

- Where are there gaps in FDA requirements?

- What resources are available?

2. Process establishment

- Integrate HF into the development process

- Define accountabilities

- Create templates and checklists

3. Competence building

- Train employees

- Incorporate external expertise

- Learn from best practices

The Johner Institute offers specialized FDA human factors training covering all aspects from planning and implementation to documentation.

5.5 Final thoughts

At first glance, FDA requirements for human factors engineering may seem complex. However, with the right understanding and a systematic approach, they are manageable. Investing in professional human factors engineering pays off in several ways:

- Faster FDA approval through complete documentation

- Safe devices with minimized application risks

- Satisfied users thanks to well-thought-out design

- Reduced liability risks through proven safety

The good news is that the harmonization between the FDA guidances and IEC 62366-1 makes it easier than ever to develop globally compliant medical devices.

Don’t consider human factors engineering as a regulatory obligation, but as an opportunity to create better and safer devices. The best medical devices are created when safety and user-friendliness go hand in hand.

Conclusion in a sentence: With a structured process, early planning, and focused implementation, you can master the FDA requirements for human factors engineering with certainty and efficiency.

The Johner Institute is happy to assist you in implementing FDA-compliant human factors, from planning and conducting tests with US users to creating the approval documentation. Contact us for a no-obligation consultation.