With PFAS, the EU plans to ban an entire class of chemicals. In doing so, it is not only threatening the supply of medical devices but also the competitiveness of EU manufacturers. After all, the assumption that manufacturers inside and outside the EU are treated equally is just one of the EU’s five misconceptions in this context.

Manufacturers should also not make mistakes and think that they are not affected or that it will not be so bad. They must act immediately!

1. PFAS: Background

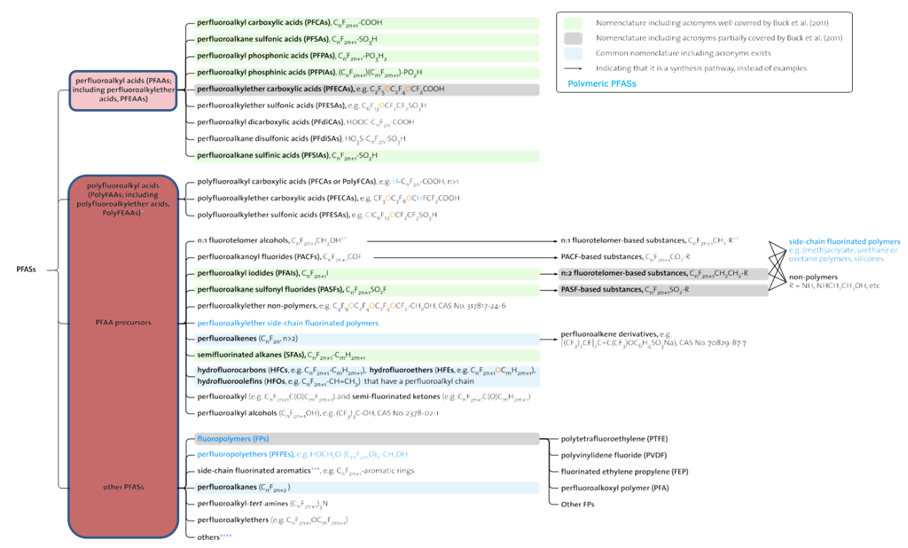

a) What are PFAS?

PFAS stands for Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (see Fig. 1). Since the 1940s, these chemicals have been used in various industrial applications and consumer products due to their unique properties, such as heat, water, and oil resistance.

PFASs can be found, for example, in non-stick cookware, food packaging, waterproof clothing, stain-resistant fabrics, firefighting foam, and many other products – including medical devices.

b) Why do they want to ban PFAS?

Many PFAS are of concern because of their potentially harmful health effects. Some studies have linked exposure to PFAS to health problems such as developmental disorders, liver damage, immune system disorders, and certain types of cancer.

PFAS compounds are persistent and can accumulate in water, soil, and organisms. They have already been detected in the blood of humans and wildlife worldwide.

c) What does the EU plan?

In response to these concerns, the European Union has taken steps to regulate and restrict the use of PFAS. As part of its chemicals strategy, ECHA has issued a proposal to ban PFASs.

The German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health writes:

If the PFAS restriction proposal is adopted, it would be one of the most extensive bans on chemical substances since the REACH regulation came into force in 2007.

Source (only available in German)

The EU’s goal is to protect human health and the environment by minimizing the release and exposure of harmful PFAS. Restricting or banning their use aims to prevent further contamination and possible health risks associated with these chemicals.

The EU plans the following transition periods:

A full ban with no derogations and a transition period of 18 months (RO1), and a full ban with use-specific time-limited derogations (18 month transition period plus either a five or 12 year derogation period)

2. Medical devices that use PFAS

PFAS are used in a variety of medical devices due to their durability, biocompatibility, and thermal, electrical, and chemical stability.

- Catheters: Certain types of catheters, especially those with lubricious coatings or hydrophilic coatings

- Instruments used for minimally invasive surgery, e.g., appendicitis; removal of the prostate, spleen, parts of the intestine or uterus; for treatment of endometriosis, etc.

- PEMS (Programmable Electrical Medical Devices) such as incubators, CT, MRI, dialysis machines, heart-lung machines, ventilators, syringe pumps

- Implants such as stents, joints

- Surgical supplies such as surgical drapes, sutures, surgical instruments, gloves

It is obvious that healthcare is not possible without these products.

MedicalMountains’ detailed position paper (only available in German) names affected medical devices and makes demands on legislators.

3. The five misconceptions of the EU

Misconception 1: The PFAS ban serves the health of citizens

The assumption that a PFAS ban would serve the health of citizens is wrong in this simplicity in several ways:

- Since substances are not degraded in nature, it does not follow that they are dangerous. On the contrary, the substances are not degraded because they hardly react, not even with the human body. This is exactly why they are used in many medical devices.

- The MDR already harms patients’ health to a large extent because medical devices are lacking. The PFAS ban will force much-needed medical devices out of the market. It is hard to do more harm to the health of vulnerable people.

- The basis for evaluating the combined toxic potential of PFAS is not yet available. Studies on PFAS have been limited by a lack of availability of analytical standards, hampered by widespread background contamination of laboratory materials, and affected by physicochemical properties such as a high surface activity that can interfere with and complicate measurements. As a result, sufficient information for quantitative risk assessment is currently available for only a relatively small number of PFASs and is not yet valid.

Misconception 2: The ban treats EU and non-EU manufacturers equally

The EU argues that manufacturers outside the EU must meet the same requirements. This is wrong because the REACH regulation only concerns products imported into the EU but not their manufacturing process. PFASs are used in many production processes without the medical devices produced necessarily containing PFASs.

EU manufacturers are not allowed to use PFASs in production; non-EU manufacturers are not subject to this regulation. As a result, production is being driven out of Europe. This is diametrically opposed to EU efforts to restore reliability to supply chains and bring manufacturers back to Europe.

Misconception 3: An exception for medical devices solves the problem

This also makes it clear why it is not sufficient to supplement the planned EU regulation with an exemption regulation for medical devices.

In many production processes, there is no need to ban the use of PFAS. They are often part of a closed system and are not released during production.

Misconception 4: The PFAS ban provides legal certainty

The announcement of the planned regulation has already caused uncertainty and had an impact on the price development of these substances. The adoption of this regulation will not bring legal certainty because many questions remain unanswered, e.g.:

- Which substances count as PFAS?

There are substances for which classification is not clearly possible. - How does one determine whether a substance contains PFAS?

The measurement methods for such a broad class of substances are incomplete. However, a law cannot be enforced if it is unclear whether it has been violated.

Misconception 5: Transition periods are sufficiently long to develop new substitutes

For many PFAS, there are currently no alternatives. It is the task of research to find these.

Even if this could be done quickly, a transition period of twelve years is not necessarily sufficient. Clinical investigations take years, as do the approval procedures. The MDR has also contributed to this.

Johner Institute experts can help you evaluate the biocompatibility of substitute substances. Contact us if you need assistance in your search for substitute materials.

4. What the legislator should do

a) Stop amendment process

The current proposal lacks the necessary impact assessment. This cannot be remedied by exempting further product classes or extending transition periods. Instead, the legislator must regulate on a risk basis.

b) Risk-based regulation instead of blanket prohibition

The level of risk is determined by the severity of possible damage and the probability that it will occur. These, in turn, depend on many factors:

- Properties of the chemical substance, e.g., its carcinogenicity

- Amount of the substance to which people are exposed

- Many medical devices use only small amounts of PFAS (in the milligram range).

- Production processes often do not release PFAS.

- Type of exposure (e.g., direct contact with blood, ingestion through the food chain)

Risk acceptance must again depend on benefits.

The proposed legislation does not consider the risks or the risk-benefit ratio. Instead of a blanket ban, these trade-offs must be made for each chemical or limited class of chemicals.

c) Establish regulatory science

To anticipate consequences, the following are needed:

- Clear and complete targets (this should include the competitiveness of European manufacturers and the healthcare of European citizens)

- Metrics that can be used to determine the degree to which goals are being met

- Models that can be used to simulate goal achievement

- Sensors in the system to be able to measure target achievement and adapt the models

It is the job of regulatory science to determine these metrics, develop models, and specify sensors.

Without an understanding of the system, it is irresponsible to try to regulate an entire economic area.

5. What manufacturers should do

a) Find out if the PFAS ban will affect them

Medical device manufacturers must first determine whether the PFAS ban affects them, for example, for the following reasons:

- The product contains PFAS.

- PFASs are used in the production process.

- Supplied components contain PFAS.

- PFAS are used in the production process of supplied components.

- Suppliers are otherwise affected by the PFAS ban.

This check is a snapshot that must be repeated.

It is conceivable that service providers and suppliers will cease operations because of the PFAS ban, even if the products supplied are not affected.

b) Consider alternatives to PFAS

Manufacturers should consider alternatives, such as:

- Substitution of PFAS with non-prohibited substances

- Modifying the product so that substances with the specific properties of PFAS are not required

This consideration must concern the entire supply chain!

This consideration must be done extremely quickly in order to meet the objection deadline.

c) File a protest

The consultation process runs until September 25, 2023. Manufacturers have until then to protest. However, this must be very well substantiated.

Previous consultation processes have rarely resulted in fundamental changes to the text of the law.

Unofficial sources said the closer the final date, the less likely changes will be considered.

6. Summary and conclusion

a) There is a lack of sincerity and insight

The planned amendment to the REACH regulation is to pass through the EU Parliament within a few months. But no one wants to take responsibility.

EU: Member states are to blame

Patrick Child, Deputy Director General of the Directorate General for the Environment, European Commission, blamed member states for EU overregulation at a June 2023 hearing:

“Member states cannot resist the wish to improve effectiveness of regulation.”

Member States: The EU is to blame

The German government blames the EU. The fact that Germany was one of the initiators of this regulation is deliberately concealed.

EU: Everyone has the opportunity to participate

Officially, there is an opportunity to provide input during the consultation process. However, the statements made so far dampen hopes that there will be significant changes to the planned tightening of the REACH regulation. The shortness of time (March to September) does not indicate that an adequate discussion can take place.

All: Regulation was lacking

Yet many subclasses of PFASs were already regulated. Even the MDR explicitly added requirements for CMR substances.

b) It is a harmful regulation

In Brussels, too, the realization is gaining ground that the MDR is more likely to harm the supply of safe medical devices. This is one of the reasons why the EU has extended the transition periods.

However, all this is of no use if the products pass the “MDR hurdle” but fail because of the PFAS regulation.

It is feared that the PFAS ban will do even more damage to healthcare than the MDR.

One manufacturer summed up the situation by saying “From stone age to modern age and back again.”

The Johner Institute supports manufacturers in

- formulating objections to this misregulation,

- the search for substitutes and their evaluation for MDR compliance, and

- the transformation of regulatory affairs departments and processes to get products to markets quickly and safely.