A vigilance system is a legally prescribed system consisting of one or more processes through which manufacturers (e.g., medical device manufacturers) record reportable incidents with their devices, evaluate them for trends, and report them to the authorities to contribute to the safety of patients and users.

This article tells you which regulatory requirements you must fulfill, how a vigilance system differs from a system for post-market surveillance, and how you can set up and operate a vigilance system quickly and in compliance with the law.

1. Definition and objectives of vigilance

There are legal requirements worldwide for monitoring medical devices on the market. The aim is to ensure and improve the health and safety of patients, users, and others. Vigilance is an important aspect of this. In some legal areas, e.g., in the USA, this is referred to as “adverse event reporting.”

The MDR Medical Device Regulation also places extensive requirements on vigilance systems. Although it defines the term “post-market surveillance,” it does not define what it means by “vigilance.” An indirect definition can be found in the now outdated MEDDEV 2.12/1 (more on this later):

“European system for the notification and evaluation of INCIDENTs and FIELD SAFETY CORRECTIVE ACTIONS (FSCA) involving MEDICAL DEVICEs, known as the Medical Device Vigilance System”

MEDDEV 2.12/1 Chapter 2 (Introduction)

Based on the global IMDRF guideline, the MEDDEV document also states the objectives of a vigilance system, namely:

To improve the protection of the health and safety of patients, users, and third parties by reducing the likelihood of a (negative) event occurring again.

2. Differentiations

a) Differentiation between vigilance and post-market surveillance

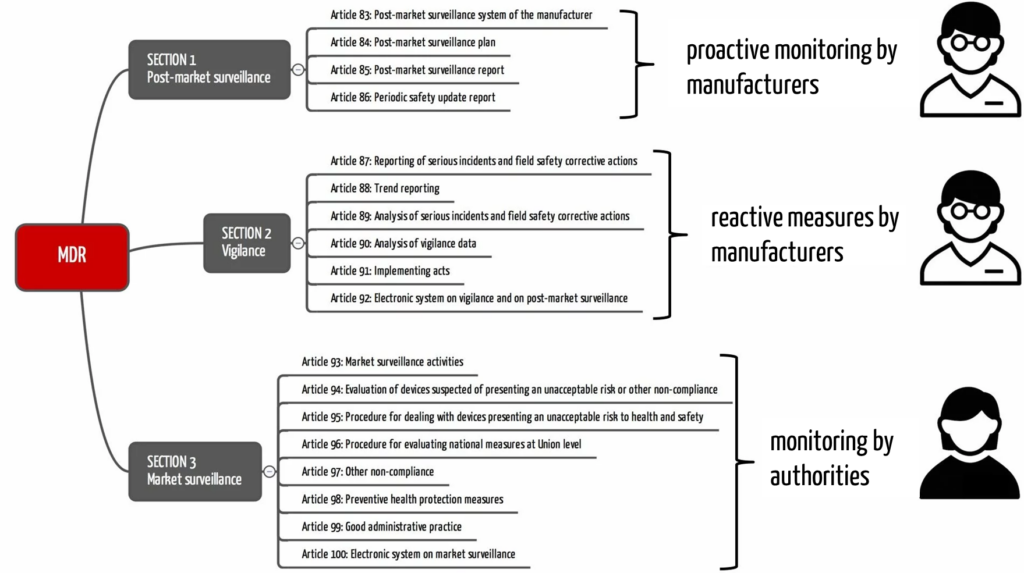

Protecting the health and safety of patients, users, and others is also the objective of post-market surveillance. However, vigilance systems and post-market surveillance systems have different objectives:

- Vigilance is a reactive system that responds to incidents.

- In contrast, post-market surveillance must be proactive. The MDR even defines post-market surveillance as proactive.

Read more here about post-market surveillance (monitoring after placing on the market).

There is also a risk of confusion between the terms “market surveillance” and “post-market surveillance.” The manufacturers are responsible for the latter just as they are for vigilance. On the other hand, market surveillance is the responsibility of the authorities.

The MDR also precisely distinguishes between vigilance, post-market surveillance, and market surveillance. It devotes a separate section to each in Chapter VII (see Fig. 1). Similarly, the FDA distinguishes post-market surveillance in 21 CFR 822 and medical device reporting in 21 CFR 803.

b) Differentiation from vigilance in medicine

The term vigilance is also used in medicine, such as in intensive care. Here, it has a different meaning:

Vigilance in medicine refers to patients’ alertness or attention. A reduced level of vigilance can range from slight drowsiness to unconsciousness.

A reduced level of vigilance can result from injuries, especially to the head, medication, or neurological diseases.

Both medical and medical device vigilance originates from the Latin word “vigilantia,” which can be translated as care or alertness.

A medical vigilance issue is a medical problem, while a medical device vigilance issue is a legal violation.

3. Regulatory requirements for vigilance

a) EU

MDR

In contrast to the old directives, the MDR has introduced a uniform reporting system with the same determinations throughout the EU. The MDR, therefore, eliminates the obligation to report nationally via the respective country-specific databases or reporting channels. Instead, there is a standardized “reporting interface” via EUDAMED. However, this can only be used once EUDAMED is fully functional. Until then, manufacturers and other actors subject to reporting requirements must continue to go through the national procedures.

The requirements for the vigilance system can be found in Articles 87 to 92 of the MDR. In general, the vigilance system regulates

- What must be reported? (i.e., what type of event, e.g., serious incidents and field safety corrective actions)

- Who must report? (i.e., which role or economic operator)

- When must be reported? (i.e., with what deadlines)

- In what form is the report made?

- What content must the notification contain?

In the following chapter, you will find a comparison with the corresponding requirements of the FDA.

In addition, the MDR regulates the requirements for national authorities to analyze vigilance data and cooperate with the competent authorities of all member states.

MDCG 2023-3

The MDCG guideline from 2023 entitled “Questions and Answers on vigilance terms and concepts as outlined in the Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices” has replaced MEDDEV 2.12/1, which had been applicable for many years until then. It guides on the topic of vigilance in a Q&A format.

For example, the document helps distinguish between “incident” and “serious incident,” interpreting reporting deadlines and the general reporting criteria. Manufacturers and other stakeholders should consider this when setting up an MDR-compliant vigilance system.

MDCG 2024-1

The MDCG document on vigilance (MDCG 2024-1) is only six pages long. Excluding the introduction, repetition of regulatory requirements, and references, only one page remains. This page contains a vigilance form.

It is up to the EU member states to decide which format must be used for submission. In Germany, for example, the BfArM form must be used.

The MDCG (similar to the MEDDEV at the time) recommends the IMDRF codes for the classification of “incidents” and “medical device problems.” This is helpful because it contributes to the harmonization of vigilance processes.

National laws and regulations

In addition to the MDR, member states can impose extended national requirements for vigilance. In Germany, for example, these can be found in the Medizinprodukte-Anwendermelde- und Informationsverordnung (MPAMIV) – the Medical Device User Notification and Information Ordinance. However, the national requirements must not contradict the requirements of the MDR. In Germany, for example, there are only additional reporting requirements, in this case, for professional users and operators of medical devices.

b) USA

Medical device reporting (21 CFR 803)

Part 803 of 21 CFR describes requirements for an adverse event reporting procedure. Unfortunately, the FDA refers to this as MDR reportable events, although this term is also used in the EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR). Misunderstandings are inevitable.

Under no circumstances should manufacturers, importers, and operators of medical devices underestimate the requirements of Part 803. This is because inadequate or even missing procedures for mandatory reporting in the USA are among the most common deviations in FDA inspections.

Tips for implementing the requirements and avoiding deviations can be found below.

Reports of corrections and removals (21 CFR 806)

The FDA requires reporting so-called “corrections” and “removals,” similar to the field safety corrective actions required by the MDR. They should not be confused with FDA recalls. A detailed overview of recalls in the FDA context and the distinction from Part 806 can be found in this article.

FDA guidance

The FDA guidance “Medical Device Reporting for Manufacturers” from 2016 provides manufacturers and other persons subject to reporting requirements with over 50 pages of comprehensive assistance to better understand the Part 803 vigilance requirements.

c) IMDRF/GHTF

The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) has adopted documents from the Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF), which no longer exists. They primarily contain global guidelines for reporting (IMDRF website on reporting guidelines).

Building on the work of the GHTF, the IMDRF deals with categorizing adverse events. In 2020, it introduced a comprehensive vocabulary with associated codes for adverse events, which is continuously updated. The objective is to enable manufacturers and authorities alike to quickly identify and analyze negative trends or new types of risk.

4. Comparison of EU and US requirements

Despite harmonization by the IMDRF, there are country-specific differences in the area of vigilance systems. This can already be seen by comparing the definitions of a reportable event according to the MDR and FDA.

a) Differences in the definition

| EU | USA | comment |

| Serious incident: an incident (= “a malfunction or deterioration in the characteristics or performance of a device already made available on the market, including errors in use due to ergonomic characteristics, as well as an inadequacy in the information provided by the manufacturer and an undesirable side effect”) that directly or indirectly led, might have led or might lead to any of the following: (a)the death of a patient, user or other person, (b) the temporary or permanent serious deterioration of a patient’s, user‘s or other person’s state of health, (c) a serious public health threat; (Article 2 65. MDR) “serious public health threat” means an event which could result in imminent risk of death, serious deterioration in a person’s state of health, or serious illness, that may require prompt remedial action, and that may cause significant morbidity or mortality in humans, or that is unusual or unexpected for the given place and time (Article 2 66. MDR) | (o) MDR reportable event (or reportable event) means: (1) An event that user facilities become aware of that reasonably suggests that a device has or may have caused or contributed to a death or serious injury or (2) An event that manufacturers or importers become aware of that reasonably suggests that one of their marketed devices: (i) May have caused or contributed to a death or serious injury, or (ii) Has malfunctioned and that the device or a similar device marketed by the manufacturer or importer would be likely to cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the malfunction were to recur. (21 CFR 803.3) (w) Serious injury means an injury or illness that: (1) Is life-threatening, (2) Results in permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure, or (3) Necessitates medical or surgical intervention to preclude permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure. Permanent means irreversible impairment or damage to a body structure or function, excluding trivial impairment or damage. (21 CFR 803.3) | – In the EU, expected side effects (if acceptable according to the risk evaluation) are only reportable in the case of negative trends. – In the USA, all undesirable side effects are reportable if they have led to death or serious injury. – Also in the US, reportable events include causes due to user errors or labeling. |

b) Further differences and similarities

The following table shows further differences and similarities:

| EU | USA | comment | |

| Is a documented procedure necessary? | yes | yes | |

| What must be reported? | – serious incident – trends of other incidents – Field Safety Corrective Action (FSCA) – serious risk emanating from the device (also only if there is reason to believe) | – MDR reportable event – reportable correction/removal | – EU: Out of EU FSCAs must be reported in the EU if the cause of the measure is not only specifically applicable to the devices in the third country – USA: In contrast to the EU MDR, the FDA requires the reporting of events that have taken place abroad if the corresponding device is also marketed in the USA and the event meets the definition of an MDR event. – USA: The FDA does not require trend reporting. – EU: Serious risk is unfortunately not defined in the MDR. However, the MDCG 2023-3 provides an interpretation. |

| Who is obliged to report? (official reporting obligation) | – manufacturers – importers – distributors – users (may be required nationally, in Germany for example for professional/ commercial users) | – manufacturers – importers – Device User Facility (e.g. a hospital, but not(!) a doctor’s practice) | – USA: Distributors are not required to report in the USA. However, they must keep records of incidents. – EU: Importers and distributors in the EU only have to report if they have reason to believe (or are certain) that the devices provided pose a serious risk. – USA: Device user facilities are only required to report incidents that have resulted in death. In addition, annual collective reports are required, including cases of “serious injuries.” |

| What is the deadline for reporting? | – serious incident: max. 15 calendar days – serious public health threat: max. 2 calendar days – death or occurrence of a serious deterioration in health: max. 10 calendar days – FSCA: Before taking the measure | – MDR reportable event: max. 30 calendar days – MDR event which „necessitates remedial action to prevent an unreasonable risk of substantial harm to public health“: max. 5 calendar days – Correction/Removal: 10 Working days after taking the measure | – The period begins from the time of becoming aware of the event. – The MDR deadlines are much shorter. – With regard to the time limits, the FDA does not differentiate whether a death or serious injury has actually occurred or not. |

| How should it be reported? | – serious incident: EUDAMED Vigilance Module (as soon as functional) – trends: EUDAMED Vigilance Module (as soon as functional) – FSCA: EUDAMED Vigilance Module (as soon as functional) – serious risk posed by the device: Notification to the respective national competent authority | – MDR reportable event: electronically via the Electronic Submission Gateway (ESG), either as a form or via machine-to-machine interface (HL7 XML via AS2 gateway) – Correction/Removal: via ESG or by e-mail | – EU: As EUDAMED is currently not fully functional, the national provisions must currently be observed. |

| What information is required? | In the EUDAMED Playground you will find a user guide with a description of the input masks and the required information. | See form3500A. You can find instructions for completing the form here. | |

| IMDRF categorization required? | yes | No, own coding | USA: The FDA offers a complete mapping of the FDA codes with those of the IMDRF. |

5. Tips on implementation

The requirements for vigilance systems vary from country to country. This makes it all the more important to know the differences and similarities. Vigilance is always a topic in audits and is subject to strict scrutiny by notified bodies and authorities such as the FDA.

The following tips help minimize deviations and warning letters from the FDA.

- Create a documented procedure for vigilance. This is a fundamental requirement. A missing or undocumented procedure will most likely lead to significant findings during an FDA inspection or even a warning letter in the worst case.

- Describe procedures and work instructions precisely, such as who has to do what, how, and how quickly in the event of an incident. Think about deputy arrangements.

- Do not try to combine the requirements of different countries. The MDR, the FDA, and other authorities worldwide have their definitions of terms, which you should not mix up. Therefore, be sure to use or refer the respective definition in the law.

- Make sure that you define terms such as “serious incident,” “MDR reportable event,” “becoming aware,” “reasonably suggest, “caused or contributed,” etc. precisely (as in the regulations). Explain these using examples that are specific to your devices.

- Due to country-specific differences, defining specific work instructions per country is advisable.

- Benefit from flowcharts and checklists. They are easier to understand than long texts.

- Document all communication (including verbal) regarding the incident.

- Train all those involved again and again. Practice the reporting system using specific examples.

Let us know if we can support you in setting up, improving, and reviewing your vigilance system, for example, with templates, further tips, training, or mock-up audits.

Change history

- 2025-02-08: Section 2.b) and therefore heading 2.a) added (objective: to avoid misunderstandings between medical personnel and regulatory affairs managers)

- 2024-02-25: Definition added at the beginning of the article

- 2024-02-09: Section on MDCG 2024-1 added

- 2023-12-11: Article completely revised