The Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) is an expert panel required by the MDR and IVDR.

The MDCG is sometimes confused with another coordination group or with expert panels. You can find out how these groups are differentiated here.

Read this article to find out how you are affected by the output of the MDCG’s work.

1. Who are the members of the MDCG?

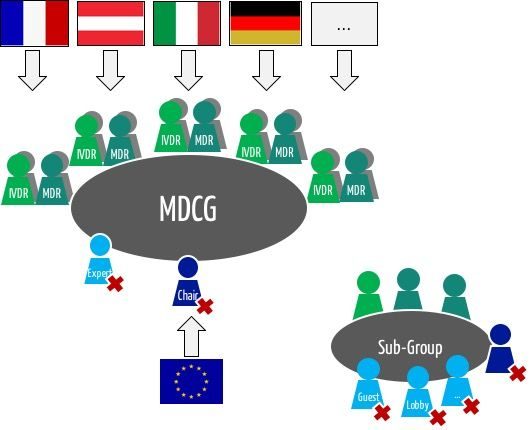

According to the MDR, the MDCG, the Medical Device Coordination Group, is a body of experts “composed of persons designated by the Member States based on their role and expertise in the field of medical devices including in vitro diagnostic medical devices […] to provide advice to the Commission and to assist the Commission and the Member States in ensuring a harmonised implementation of this Regulation.”

According to Article 103 of the MDR, “the members of the MDCG shall be chosen for their competence and experience in the field of medical devices and in vitro diagnostic medical devices.” On the other hand, the article also clarifies: “They shall represent the competent authorities of the Member States.”

The member states appoint several members:

“Each Member State shall appoint to the MDCG […] one member and one alternate each with expertise in the field of medical devices, and one member and one alternate with expertise in the field of in vitro diagnostic medical devices […]”. This means that the coordination group has around 60 members.

“The MDCG may invite, on a case-by-case basis, experts and other third parties to attend meetings or provide written contributions.”

The MDCG may set up subgroups to “have access to necessary in-depth technical expertise in the field of medical devices including in vitro diagnostic medical devices,” as the MDR writes. Whether these subgroups overlap with the “Expert Panels” (see below) is currently unclear.

Thirteen subgroups, organized by topic, offer advice and produce guidelines on their areas of expertise.

The Member States appoint the sub-group members for a three-year term of office. Stakeholders participate as observers. They are also appointed for three years following a call for applications.

The members of the Coordination Group meet regularly under the chairmanship of the EU Commission.

2. Tasks of the MDCG

The Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) primarily has an advisory and coordinating function. It is not authorized to make decisions and is only consulted by the Commission before the Commission, for example,

- decides whether a device falls within the scope of the Regulation (Article 4, Article 51),

- adopts Common Specifications (Article 9), or

- lays down details on the notification system (e.g., form, deadlines, measures) (Article 91).

The Commission consults the MDCG when it appoints expert panels or specialized laboratories, appoints consultants to expert panels, and includes them in a central list (Article 106).

The MDCG draws up a market surveillance program that the competent authorities must observe (Articles 93, 105).

The MDCG may request scientific opinions from expert panels on the safety and performance of a device where there are justified concerns (Article 55).

- Supervision of Notified Bodies (NBO)

- Standards

- Clinical Investigation and Evaluation (CIE)

- Post-Market Surveillance and Vigilance (PMSV)

- Market Surveillance (MS)

- Borderline Devices and Classification (B&C)

- New Technologies

- EUDAMED

- Unique Device Identifier (UDI)

- International Affairs

- In vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVD)

- Nomenclature

- Annex XVI devices

a) EUDAMED

Also, in the context of EUDAMED, the Commission must consult the MDCG (not ask for its consent) before

- establishing or operating a UDI database (Article 28),

- establishing or operating a system generating unique registration numbers (Article 30),

- establishing and operating a system managing information on notified bodies and certificates of conformity (Article 57),

- establishing, maintaining, and updating the EUDAMED (Article 33), and

- publishing an audit report (Article 34).

b) Designation of notified bodies

The Medical Device Coordination Group (the MDCG) plays a vital role in the designation and review of notified bodies.

- The MDCG and the Commission appoint an assessment team to review applications from notified bodies for designation (Article 39).

- The MDCG makes a recommendation as to whether designation should take place. The (national) authorities (e.g., ZLG) must justify any deviation from this recommendation (Article 43).

- The MDCG will be involved in the monitoring and reassessment of notified bodies (Articles 44, 45). This also applies if the competence of a notified body is contested (Article 46).

3. Publications of the MDCG

The MDCG publishes its documents in the EU DocsRoom.

The MDCG has published the schedule for the publication of further guidelines in April 2022.

The latest original publications are:

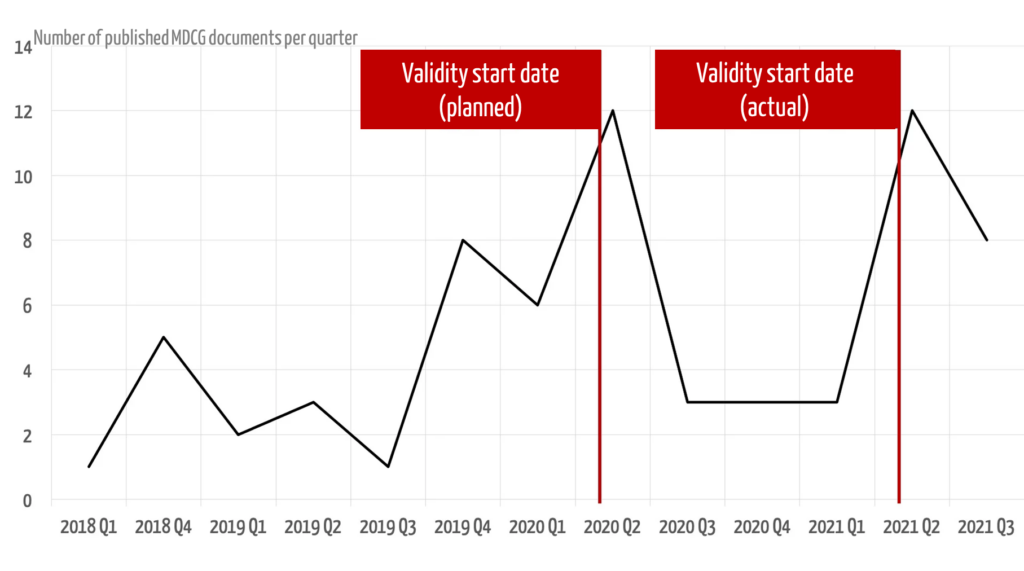

The publications mainly appeared at the times when the MDR was to become or had become valid.

A regulatory system should be communicated in full and in good time so that it can be implemented by the parties concerned. The MDR was published in May 2017, at which point it would have been desirable and helpful if all MDCG guidelines had been published. Four years later, this is still not the case.

In October 2019, the MDCG published a roadmap for further documents to be created or revised in the coming months and years.

You can download the MDCG roadmap (as of October 2021) here.

a) MDCG on “MDSW under MDR or IVDR”

The document “Guidance on Classification for Software in MDR 2017/745 and IVDR 2017/746” has now been published. In this document, the MDCG sheds light on how “Medical Device Software” (MDSW) is to be classified and evaluated under MDR and IVDR. The document aims to at least partially form the basis for a successor to MEDDEV 2.1/6.

i) Software that only influences should not be MDSW?

The MDCG’s conclusion that software that exclusively controls and influences a medical device is not medical device software may be confusing:

If, for example, the control of a surgical robot is completely outsourced to external software and this software decides, for example, based on input signals, whether a tissue is diseased and must be cut away or spared as healthy tissue, then this very much speaks for a medical intended purpose. Such software would, therefore, have to be an accessory for a medical device.

The document does not contradict this; however, the distinction between software that is a medical device but is not medical device software and software that counts as a medical device and as MDSW is not necessarily intuitive.

An adequate discussion of the circumstances under which software should be classified as an accessory would be desirable.

ii) Reinterpretation of terms

The document is also rather disturbing in other respects. For example, it only wants the terms “prediction” and “prognosis” to be understood in the context of diagnoses. Where does this appear in the MDR or the IVDR?

Predicting the course of a disease is not a diagnosis; neither is the probability that a patient will suffer from a disease in the future. Nevertheless, both are a prediction or prognosis.

iii) Confusion

Both the examples and the wording do not achieve the document’s objective, which is to clarify how software is to be handled in the context of the MDR and IVDR.

For example, what is “software with built-in electronic controls”? The opposite, namely electronic controls with built-in software, seems more likely.

The discussion as to whether the software is a medical device seems at least ambiguous:

A firmware in a clinical thermometer that only converts the voltage of the thermistor into temperature is, of course, not a medical device (but the clinical thermometer is). This would not change even if the software were to calculate the dose of the appropriate medication.

iv) Classification and Rule 11

Perhaps the most important implication of this document is that Rule 11 is by no means limited to standalone software. You will find here a detailed discussion of Rule 11 in light of this MDCG publication.

v) Conclusion

It is to be hoped that the document will not become valid in this form. Manufacturers are already sufficiently challenged by the lack of “usability” of the MDR and IVDR (read, for example, Paragraph (8) of Article 120 of the MDR). There is certainly no need for sources of further confusion, nor is there any need for an additional tightening of the classification.

b) 2019-16 on cybersecurity

According to the MDCG, the 44-page document is intended to help manufacturers meet the cybersecurity requirements of Annex I of the MDR and IVDR. However, it is not limited to the defined regulatory framework (Annex I) or the target group (manufacturers).

Relevant requirements of MDR and IVDR

The document explains which requirements of the EU regulations relate to cybersecurity as a whole. These can be found in Annex I:

- Risk management

- Combination of devices

- Interaction between software and the IT environment

- Interoperability and compatibility with other devices

- Dependability, repeatability, performance

- Unauthorized access

- Lay users

- Supporting materials

It also lists the other relevant articles and annexes:

- Post-market surveillance including plan and reports

- Vigilance

- Technical documentation

- Clinical evaluation and post-market clinical follow-up

Chapter 2: Basic concepts

The chapter on “Basic Cybersecurity Concepts” is written like a textbook. It provides definitions, although the term cybersecurity is missing.

The authors emphasize that IT security can only be achieved by manufacturers, integrators, operators, and users all working together.

Chapter 3: Development of safety devices

The third chapter remains similarly general in parts. Statements such as “the primary means of security verification and validation is testing” are correct but of limited benefit.

More useful, although not surprising, are examples

- for physical access protection to the medical device,

- for security measures in the operating environment, such as firewalls,

- for security measures for data traffic, such as network segmentation, and

- for patch management requirements.

Chapter 4: Documentation and accompanying materials

Guideline 2019-16 dissects Paragraph 23 in Annex I in great detail. This sets out requirements for the instructions for use. The guideline interprets the requirements and lists aspects that the documentation must contain.

It remains unclear why the authors came up with the respective examples and why they included them. Why, for example, are “sufficiently detailed network diagrams for end-users” required?

Chapter 5: Post-market surveillance and vigilance

The fifth chapter remains relatively unspecific with regard to IT security. The IMDRF codes for reportable problems are an exception.

Chapter 6: Reference to other regulations

The MDCG 2019-16 document refers to other regulatory documents:

- NIS Directive 2016/1148 (Directive on the safety of network and information systems)

- GDPR

- IMDRF Guideline on the cybersecurity of medical devices

Chapters 7 to 10: Appendices

Chapter 7 contains a useful appendix with a mapping of the MDR requirements to the requirements of the NIS Directive.

Chapter 8 gives examples of IT security issues and the impact on safety.

Chapter 9 lists relevant standards.

Chapter 10 shows the interaction between “normal” risk management and “cybersecurity risk management.”

Conclusion

Even after reading the document several times, it leaves you somewhat perplexed and with a “so what?”. Anyone who knows a little about IT security will learn little new. Those who don’t will not understand what is written. The didactic level is not sufficient for this.

The impression remains that this is just another document attempting to explain IT security basics. The guideline only partially does justice to the claim of providing concrete guidance on how to meet the requirements of the MDR and IVDR with regard to IT security.

It would be desirable for the MDCG to adopt a similar stringency and methodology for quality assurance when writing new documents as is customary in (many) standards bodies and scientific publications.

Manufacturers do not need a flood of documents but rather concrete instructions on interpreting and implementing the EU regulations.

4. Differentiation from other groups and committees

Do not confuse the Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) with the Coordination Group of Notified Bodies and other expert bodies.

a) Expert Panels

According to Article 106, the expert panels “advisors appointed by the Commission on the basis of up-to-date clinical, scientific or technical expertise in the field and with a geographical distribution that reflects the diversity of scientific and clinical approaches in the Union. […] The members of expert panels shall perform their tasks with impartiality and objectivity. They shall neither seek nor take instructions from notified bodies or manufacturers.”

These expert panels have the following tasks:

- They shall advise notified bodies and manufacturers “inter alia, the criteria for an appropriate data set for assessment of the conformity of a device, in particular with regard to the clinical data required for clinical evaluation, with regard to physico-chemical characterisation, and with regard to microbiological, biocompatibility, mechanical, electrical, electronic and non-clinical toxicological testing.”

- They draw up “an opinion on clinical evaluation assessment reports of notified bodies in the case of certain high-risk devices.” This opinion or assessment is required for implantable devices. The Medical Device Coordination Group “may, based on reasonable concerns, request scientific advice from the expert panels in relation to the safety and performance of any device.”

- The expert panels also support the Commission in drawing up Common Specifications, particularly in the context of clinical evaluations and clinical investigations.

- The guidelines, such as 2019-16 on cybersecurity, formulate very specific requirements that manufacturers must observe in the development and monitoring of their devices.

b) Coordination Group of Notified Bodies

The Medical Device Coordination Group should also not be confused with the Notified Bodies Coordination Group required by Article 49 (“Coordination of Notified Bodies”):

The Commission shall ensure that appropriate coordination and cooperation between notified bodies is put in place and operated in the form of a coordination group of notified bodies in the field of medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic medical devices. This group shall meet on a regular basis and at least annually. […] The Commission may establish the specific arrangements for the functioning of the coordination group of notified bodies.

Such a coordination group of notified bodies already exists in the form of the Notified Bodies Operation Group NGOB, which has achieved notoriety with its NBOG documents.

There is also the Team-NB with its NB-MED documents.

5. MDCG: Summary, conclusion, and criticism

a) Who the MDCG concerns

The work of the Medical Device Coordination Group directly affects notified bodies, medical device manufacturers, and their service providers:

- The MDCG recommends when devices should fall under the MDR or IVDR.

- It increases the pressure on notified bodies, passed on to them during audits and technical documentation reviews.

- The MDCG is also consulted when new Common Specifications are created that you must comply with.

- If a coordination group has doubts about the safety of your device, it can request an opinion from the expert committees.

b) Unclear liability

The MDCG appears to be a largely toothless tiger. Work is assigned to this body, and it is consulted. But it is not allowed to make decisions.

However, many auditors of notified bodies regard the MDCG’s publications as “state of the art” and, therefore, as laws. This is even though the MDCG itself writes in its guidelines:

The document is not a European Commission document and it cannot be regarded as reflecting the official position of the European Commission. Any views expressed in this document are not legally binding and only the Court of Justice of the European Union can give binding interpretations of Union law.

e.g., MDCG 2019-16

The MDCG is making things far too easy for itself with these “disclaimers”. Even the European Court of Justice (ECJ) referred to the predecessor document of the MDCG 2019-11 guideline, MEDDEV 2.1/6, in its ruling on software items.

It must be clear to the authors that their publications are understood to be binding.

c) Non-transparent and undemocratic decisions

Precisely because the documents have this binding character, it cannot and must not be the case that their creation is completely non-transparent. The meetings take place behind closed doors.

Even members of this body complain that its decisions and documents have subsequently been changed.

The fact that de facto legal documents are created without any parliamentary process is not worthy of a democracy. It is precisely this kind of behavior that fuels disenchantment with politics and rejection of the Brussels institutions.

d) Unclear competence of the “experts”

It remains to be seen whether the member states will really appoint the best experts to the coordination group and not simply representatives of the authorities. The statement, therefore reads almost like an admission:

“The MDCG may invite, on a case-by-case basis, experts and other third parties to attend meetings or provide written contributions.”

As explained above, the publications to date do not always allow the conclusion that those persons who are best versed in the respective domain are involved.

e) Hope

However, there are more justified hopes that the Medical Device Coordination Group

- will help to ensure that the quality of notified bodies becomes more uniform throughout Europe,

- the work of manufacturers will not be significantly hindered, and

- is freer from financial or other interests than experts from the medical device industry or lobby associations would be.

It is doubtful that these hopes are justified, given the draft classification of medical device software described above.

Even in the context of the “Medical Device Coordination Group,” the MDR remains true to the principle that the EU Commission has the final say everywhere.

Change history

- 2023-05-16: Current MDCG documents added

- 2022-11-25: Current MDCG documents added

- 2022-09-08: German translations of MDCG 2022-14 under 3. added

- 2022-05-06: MDCG 2022-6 added to the table

- 2022-04-28: MDCG 2022-5 added to the table

- 2022-04-11: Timing of the MDCG added to chapter 3

- 2022-02-25: Current MDCG-Guidances added

- 2022-01-27: Current MDCG-Guidances added

- 2021-12-10: Current MDCG documents added

- 2021-11-15: The MDCG roadmap (as of October 2021) added

- 2021-07-27: Graphic added to the 3rd section