The classification of in-vitro diagnostics (IVD) can have far-reaching consequences, as it has an impact on the conformity assessment procedure, certification audits, and, thus, on market launch.

To help you prevent the unnecessary allocation of your IVD product to a high-risk class, this article provides an overview of

- how your product qualifies as an IVD,

- how IVDs are classified according to the IVDR, and

- how you can avoid an unnecessarily high classification.

1. What qualifies a product as an IVD?

a) Medical purpose and qualification as a medical device

If you look at the definition of an IVD according to Article 2 (2) of the IVDR, it states that every IVD is also a medical device: “‘in vitro diagnostic medical device’ means a medical device that […]“. Therefore, when considering the qualification of a product as an IVD, the definition of a medical device must first be taken into account:

“medical device means any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, implant, reagent, material or other article intended by the manufacturer to be used, alone or in combination, for human beings for one or more of the following specific medical purposes:

- diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, prediction, prognosis, treatment or alleviation of disease,

- diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation of, or compensation for, an injury or disability,

- investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological or pathological process or state,

- providing information by means of in vitro examination of specimens derived from the human body, including organ, blood and tissue donations,

and which does not achieve its principal intended action by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means, in or on the human body, but which may be assisted in its function by such means.

The following products shall also be deemed to be medical devices:

- devices for the control or support of conception;

- products specifically intended for the cleaning, disinfection or sterilization of devices as referred to in Article 1(4) and of those referred to in the first paragraph of this point.

Article 2 MDR

According to the definition of a medical device, every medical device must have a “specific medical purpose“. The 4th indent of the definition of a medical device specifies “providing information by means of in vitro examination of specimens derived from the human body […]” as a medical purpose and thus refers to in vitro diagnostics (IVDs), which are a subgroup of medical devices.

However, according to Art. 1 (6) of the MDR, the MDR “does not apply to (a) in vitro diagnostic medical devices covered by Regulation (EU) 2017/746“; the IVDR applies to IVDs as a specific regulation.

b) Qualification as an IVD

In vitro diagnostic medical devices are therefore a subgroup of medical devices that obtain medical or diagnostic information from human samples. The type of information provided by an IVD is further specified in the definition of an IVD:

“in vitro diagnostic medical device means any medical device which is a reagent, reagent product, calibrator, control material, kit, instrument, apparatus, piece of equipment, software or system, whether used alone or in combination, intended by the manufacturer to be used in vitro for the examination of specimens, including blood and tissue donations, derived from the human body, solely or principally for the purpose of providing information on one or more of the following:

a) concerning a physiological or pathological process or state;

b) concerning congenital physical or mental impairments;

c) concerning the predisposition to a medical condition or a disease;

d) to determine the safety and compatibility with potential recipients;

e) to predict treatment response or reactions; or

f) to define or monitor therapeutic measures.

Specimen receptacles shall also be deemed to be in vitro diagnostic medical devices;”

Article 2 IVDR

Accordingly, IVDs are devices intended by the manufacturer for the “in vitro examination of specimens […] derived from the human body” and intended “solely or principally to provide information” for an in vitro diagnostic purpose as listed in IVDR, Art. 2 (2) Subsections a) to f).

c) Borderline cases for qualification as an IVD

However, in some cases, the decision as to whether a product is an IVD or not is unclear.

The “Manual on borderline and classification for medical devices under Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices” is intended to help with uncertainties. However, the third version from September 2023 version still contains numerous empty chapters. The “Manual on Borderline and Classification in the Community Regulatory Framework for Medical Devices” in version 1.22 from 2019 and MEDDEV 2.14/1 “IVD Medical Device Borderline and Classification issues“, which can provide IVD manufacturers with clarity, are a valuable addition. The manual and the guideline describe borderline cases of IVD qualification. Section 1.4 of MEDDEV 2.14/1 deals with the distinction between IVDs and “products for general laboratory use”.

The MDCG 2024-11 Guidance on qualification of in vitro diagnostic medical devices also considers various issues relating to the qualification of products as IVDs and provides supporting examples.

You can find further information on the topic in our article “General laboratory equipment: What manufacturers and laboratories need to know to avoid problems and unnecessary expense.“

If samples derived from the human body are analyzed with a product for an in-vitro diagnostic purpose, this product must be qualified as an IVD according to the IVDR and classified accordingly in risk classes A, B, C, and D.

2. Why the correct classification is important

Incorrect classifications can lead to deviations in the audit and in the product inspection by the notified body. In the event of differences of opinion between the manufacturer and the notified body, the matter is referred to the competent authority. In the worst case, the latter classifies the product in an unnecessarily high class, which inevitably leads to a delay in market launch. Competitors can also query the classification and use actions for an injunction to prevent the marketing of the products.

Therefore, it is critical that IVD products are classified correctly under the IVDR to prevent these problems.

You can find tips on how to do that further down in this article.

3. Classification according to the IVDR

The classification of IVD is based on Annex VIII of the IVDR and is divided into two sections:

- The first section contains general rules for the allocation of the classification, the so-called implementing rules. These relate, for example, to product dependencies or rules in the event of conflicts.

- The second section contains seven rules for allocating IVD to risk classes A to D.

3.1 General rules for the implementation of classification according to the IVDR

The IVDR provides rules for the implementation of the classification, the so-called implementing rules (IVDR Annex VIII, Section 1).

Intended purpose

“Application of the classification rules shall be governed by the intended purpose of the devices” (IVDR Annex VIII 1.1.). With this, the manufacturer specifies the medical purpose for which their device will be used. The intended purpose ultimately determines the classification, depending on the risk.

The intended purpose can be found on the labeling, in the instructions for use, and in the advertising materials for the product. It makes the product an IVD.

Read more about the intended purpose of medical devices and IVDs in our article “Intended purpose and intended use: more serious than you think!” (German).

If your product is placed in a higher risk class than you expected, the intended purpose may not have been determined correctly.

Dependencies of products

If an IVD is used with other IVD devices, there are two options regarding the classification. In principle, “If the device in question is intended to be used in combination with another device, the classification rules shall apply separately to each of the devices” (IVDR Annex VIII 1.2.). For example, an ELISA reader can be classified independently of an antibody-based reagent kit if both are placed on the market as separate devices.

The situation is similar for accessories. “Accessories for an in vitro diagnostic medical device shall be classified in their own right separately from the device with which they are used” (IVDR Annex VIII 1.3.). A digital camera can be connected as an accessory to a microscope specifically intended for pathology so that a second pathologist can view the histological section simultaneously. If the camera is defined as an accessory, it is classified separately from the microscope.

“Accessory for an in vitro diagnostic medical device” means an article which, whilst not being itself an in vitro diagnostic medical device, is intended by its manufacturer to be used together with one or several particular in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) to specifically enable the in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) to be used in accordance with its/their intended purpose(s) or to specifically and directly assist the medical functionality of the in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) in terms of its/their intended purpose(s)”.

Article 2(4) IVDR

However, if components are combined to form an IVD medical device, they are classified together (same risk class). This applies, for example, to a PCR kit consisting of buffer, enzyme, primer, and probes. The same applies to calibrators (IVDR Annex VIII 1.5.) and control materials with quantitative or qualitative assigned values (IVDR Annex VIII 1.6.), which are intended for use with an IVD device; they are assigned to the same class as the device.

Software

The following applies to software: If software fulfills its own medical purpose, it is classified separately. However, if the software controls a device or influences its use, it is assigned to the same class as the device (IVDR Annex VIII 1.4.). Software that controls a laboratory device (start, stop), monitors it, remotely determines the plate assignment, or assesses the quality of measurement results is classified together with the device.

Examples and more precise descriptions of the classification of IVD software can be found in our article “Classifying IVD software correctly.”

Please also note:

- If a device has multiple intended purposes associated with different risk classes, the entire device is classified in the highest class.

- If several classification rules apply, the rule of the highest class is applied.

- Each classification rule applies not only to first line assays but also to confirmatory and supplemental assays.

- All classification and implementation rules must always be considered to determine which class the device falls into.

3.2 Application of the seven classification rules for risk classes A-D

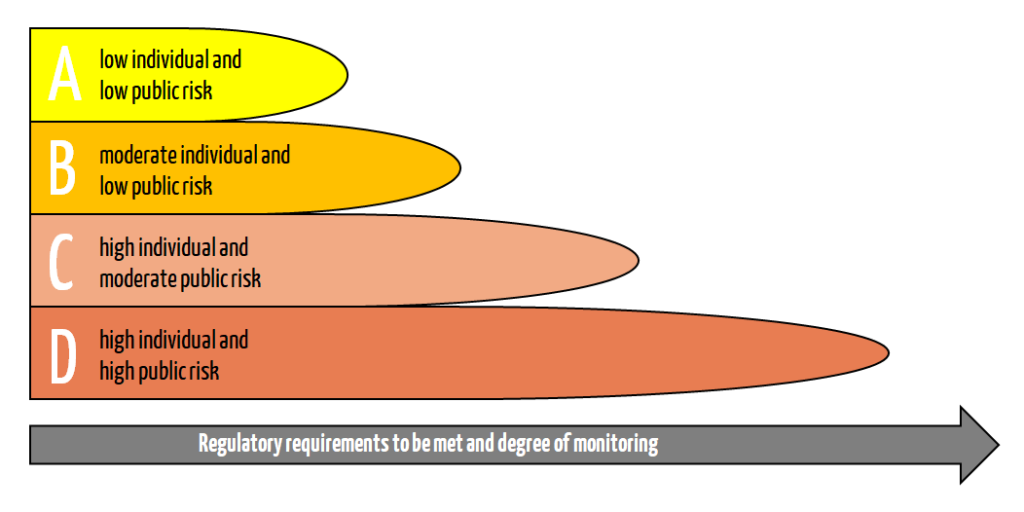

The second part of Annex VIII contains the seven decisive rules for assigning the appropriate risk class. The IVDR divides IVDs into the four risk classes A, B, C, and D. The allocation depends on the hazards that may emanate from the IVD.

All seven rules must always be taken into account. However, the rule of thumb of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) can initially be used for the allocation. This is:

The greater the risk of a life-threatening disease and the larger the group of people affected, the higher the risk class.

For the individual risk classes, this means:

Class D – life-threatening infections – highest risk

High individual and high public risk

In the case of class D products, an incorrect result presents a life-threatening risk for several individuals (rules 1 and 2).

Class D includes products for:

- Evidence of transmissible pathogens that cause a life-threatening disease with a high risk of spreading (rule 1)

- Example: the detection of highly contagious and dangerous pathogens such as Ebola, SARS, Lassa, and Marburg viruses

Warning! Depending on the intended purpose: HIV, measles, MRSA, MRGN

- Example: the detection of highly contagious and dangerous pathogens such as Ebola, SARS, Lassa, and Marburg viruses

- Determination of the degree of infection of a life-threatening disease as part of monitoring for patient management (rule 1)

- Example: Degree of infection in tuberculosis patients

- Evidence of transmissible pathogens for the suitability of blood, cells, tissues, or organs for transfusions or transplants (rule 1)

- Example: Tests that detect the HIV, HCV, HBV, HTLV status in blood reserves

- Devices used for blood grouping or for the determination of foeto-maternal blood group incompatibility or for tissue typing in the context of transfusion or transplantation medicine (rule 2)

- Markers in the AB0 system, the Rhesus system, the Kell system, the Kidd system, and the Duffy system

- Note: Tests for the determination of other markers are assigned to risk class C

Class C – products with a high risk

High individual and moderate public risk

In the case of class C products, an incorrect result presents a life-threatening risk to an individual (rule 3).

Class C includes products for:

- Blood group determination, tissue typing of unlisted markers

- Example: HLA typing

- Determination of the immune status of women for transmissible pathogens during a prenatal screening (CMV tests in pregnant women)

- Companion diagnostics (EGFR (lung cancer), BRAF (skin cancer), KRAS (bowel cancer))

- Cancer screening, diagnosis, determination of stage (PAP test, CIN test (determination of the stage of cervical cancer))

- Genetic tests in humans (carrier testing, BRCA1/2 (predisposition to breast cancer), HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 (celiac disease))

- Genetic disorders in an embryo or fetus (NIPT (fetal trisomy, microdeletions))

- Testing of infectious pathogens with an existing risk of a life-threatening situations in the event of anincorrect result

Class C/B – Devices for self-testing and near-patient tests

IVD devices for self-testing are generally categorized into risk class C (rule 4).

Example of a class C self-test:

- Indicator tests

- Sampling sets provided that the lay user is required to do more than just a simple sample collection

Exceptions are pregnancy tests, ovulation tests, tests for the determination of cholesterol levels, or tests for the detection of glucose, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and bacteria in urine. These tests are assigned to class B (rule 4).

Near-patient tests are classified independently, i.e., according to their outgoing risk. This means near-patient tests can be classified into class B, C, or even D.

Class B – fallback class

Moderate individual and low public risk

In the case of class B products, there is no life-threatening risk in the event of an incorrect result (rules 6 and 7).

Class B should be viewed as a “fallback class.“

- Products that do not fall under rules 1 to 5 are assigned to class B.

- Control devices with no assigned quantitative or qualitative value are allocated to class B.

Class A – laboratory equipment

Low individual and low public risk

Products in risk class A do not produce any results (rule 5).

These include:

- Instruments specifically intended for in-vitro diagnostics, insofar as no integrated software for the specific calculation of results associated with a medical purpose is included

- Examples: Quantitative PCR thermocycler, sequencer, mass spectrometer, ELISA reader, flow cytometer

- Specimen receptacles

- Examples: Urine pots, saliva tubes, EDTA blood sample tubes, containers for swabs

- Products for general laboratory equipment: Accessories with no critical features, buffer solutions, washing solutions

- Examples: Special buffers for preserving or pre-treating cells; special coated vessels that prevent disruptive factors for a given test

- General culture media and histological stains for specific IVD tests

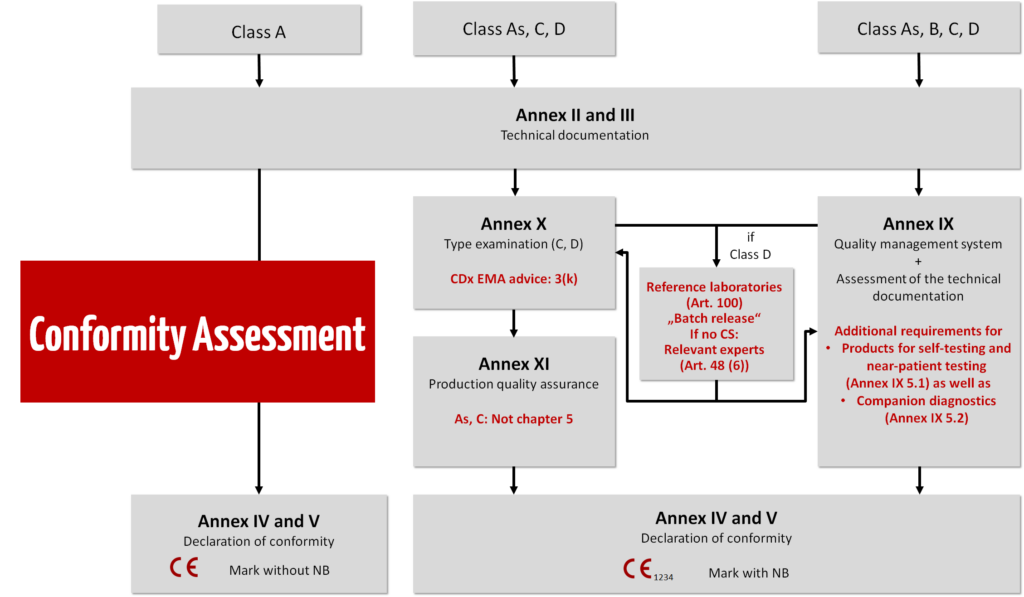

4. Consequences of the classification

The risk class determines the conformity assessment procedure.

Class D

An intensive audit is carried out in the highest IVD risk class.

The reference laboratory randomly tests each batch of reagents manufactured. In the case of novel IVDs in this class, the scrutiny procedure is also used (procedure in which the notified body appoints a committee of experts as part of the conformity assessment; Article 50 IVDR).

For notified bodies, the MDCG has published the document “Verification of manufactured class D IVDs by notified bodies” on class D IVDs. Please also refer to the EU Common Specifications for class D IVDs.

Class C

Class C devices are treated in the same way as class B devices, but manufacturers of class C and D devices must prepare an periodic safety update report, at least once a year, in accordance with Art. 81 IVDR. In the case of special products such as near-patient tests (POCT; Point-of-Care Testing) or test for self-testing, there is a particular focus on usability. In the case of Companion Diagnostics (CDx), the focus of testing is on the acquisition of the medicinal product with the involvement of the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Class B

From class B and above, the QM system is audited by the notified body and the technical documentation is checked. If you form product categories, only representative products in a category are tested.

You can find more information about product groups and categories in our article “Generic device group versus device category.” (German)

Class A

- For class A IVDs, manufacturers do not need to involve notified bodies, in other words the documents do not need to be checked by a notified body. The documents can, however, be requested by the authorities. According to Article 10(8) IVDR, manufacturers need a full quality management system (ISO 13485).

- In the case of instruments and products that are also machines, the EMC Directive and the Machinery Regulation apply.

- In the case of sterile products such as specimen receptables, corresponding standards such as the EN 556 series apply.

Note: Even class A manufacturers need a notified body to inspect the sterile aspects. Their inspection, however, is limited exclusively to this area.

Basic safety and performance requirements

Regardless of the classification, manufacturers must meet the applicable underlying safety and performance requirements set out in Annex I of the IVDR. Evidence of compliance with the latest technology must therefore be documented for all classes, including class A:

- Risk management

- Usability

- Verification and validation

In the case of products that are software or contain software, further evidence is needed:

- Software life cycle

- IT security

5. How to classify in a smart manner

Incorrect or at least unfavorable classification into risk classes can occur with IVDs. In most of these cases, the product ends up in a class that is too high and is therefore inspected more intensively than necessary.

This mainly occurs when manufacturers focus on the possible uses of the product and not on the defined intended purpose (in other words only the intended use). What is relevant, however, is what the product is intended for and not the uses that can occur in deviation from this.

Targeted measures and arguments can avoid the most common classification errors. We set out three typical problems when carrying out classifications according to IVDR and their possible solutions.

Learn how to qualify your IVD safely, how the classification of IVDs under the IVDR works, how to create a plan to implement the regulatory requirements, and finally, how to check the compliance of your file with the help of the Medical Device University.

a) Breaking systems down into products

Problem:

With the new IVDR classification system, numerous products made up of various parts are allocated to a higher class. An analysis system, for example, moves to the highest class due to a single critical component. For most parts of the system, though, this is not necessary.

Example:

You combine an IVD analysis device, a sample preparation robot, and software to interpret the results into a system. The system is described as a whole in the technical documentation and is sold as a complete solution. The classification for the entire system is then dependent on the biomarkers tested and the clinical statement made using the system.

Using the described analysis system to provide evidence of antibodies for determining allergy status can lead to categorization into class B as per rule 6. In case the system is applied simultaneously to determine the immune status of pregnant women concerning potential cytomegalovirus infection (CMV), it would fall under class C. Similarly, when the system is used to evaluate the compatibility of blood reserves for potential recipients, its classification will be class D.

Solution:

Clever separation is the key to a differential classification. This leads to a more streamlined and speedier authorization scenario. The payoff for this is that you have to create technical documentation for each of the combined individual products.

You can break this system down into individual products and describe their interfaces in such a way that they achieve their purpose when they are combined. Each system component then has its own intended purpose and its own technical documentation. This means that at least the analysis device can fall into class A and the reagent product into a higher class depending on its intended purpose.

b) Optimizing the classification with smart software architecture

Problem:

The clinical statements in the results report go well beyond the intended purpose as formulated. This indirectly catapults the product into a higher class or creates special cases that additionally need to be assessed by the notified body.

Example:

IVD software with the intended purpose “to determine the pathogenicity of genetic variants” comes under class C, as this is mostly cancer diagnosis or genetic tests (determination of hereditary diseases). If in addition to determining the pathogenicity of the variant the results report also suggests a medicinal product as treatment or potentially even provides information on the safety of the medicinal product in the context of the variant(s) identified, this is companion diagnostics.

This is a special case in the inspection of technical documentation. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) needs to be involved.

Solution:

Technology platforms can be constructed as modular systems with the modules each describing separate software. This involves the creation of several technical documentation files, but the platform itself does not even need to be qualified as a medical device. Software architects who can show why the modules are independent of one another are needed for this solution.

As this example shows, in addition to its medical purpose software mostly also carries out numerous non-medical functions. The classification of IVD software is therefore extremely complex. We examined the topic in more detail in the article ”Classifying IVD software correctly.”

c) Break reagent kits down into components

Problem:

Many manufacturers offer similar reagent kits. Although the individual components overlap, they are described again for each individual kit. Many parts of the technical documentation contain redundant information.

Some manufacturers also offer kits with multiplex evidence. In this case, the highest class applies depending on the intended purpose of the critical parameter. As a result, the entire kit moves into the higher class B, C, or D based on the intended purpose.

Solution:

Most reagent kits are component-based from the outset: buffer, enzymes, analyte-specific reagents such as primers, probes, or antibodies, controls and where appropriate calibrators all work together. The kits can be broken down into components. Kit 1 then contains, for example, the generic parts. The generic part only needs to be described once, as it is always the same. This kit then comes under class A. Kit 2 comprises the analyte-specific components and would fall into a higher risk class.

This means more technical documentation is needed, but it is more streamlined and can be expanded like a modular system.

6. Sources that help with classification

To help you decide which class to assign your device to, you can also refer to other sources in addition to the IVDR. These include:

- Guidance document – In vitro diagnostic medical devices – Borderline and Classification issues. A guide for manufacturers and notified bodies – MEDDEV 2.14/1 rev.2

- MDCG 2020-16 rev. 4 “Guidance on Classification Rules for in vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices under Regulation (EU) 2017/746”; Team NB has published a statement on the classification of SARS-CoV-2 tests

- Manual on borderline and classification for medical devices under Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices Version 4: The EU Commission’s Borderline Manual is not yet complete and only helps with classification to a limited extent. Until a complete version is available, the predecessor document Manual on borderline and classification in the Community Regulatory framework for medical devices can be regarded as state-of-the-art and used for classification.

- Principles of In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) Medical Devices Classification IMDRF/IVD WG/N64

7. Conclusion

The IVDR divides IVDs into four different risk classes (Class A, B, C, and D). If manufacturers do not proceed correctly, their devices will be assigned to an unnecessarily high class. As described in the article, this can have far-reaching consequences.

By precisely describing the intended purpose and cleverly delimiting the components, over-classification of IVD devices can be avoided, and the technical documentation can be streamlined simultaneously.

Please do not hesitate to contact the Johner Institute if you have any questions about the segregation strategy or classification. You can use the contact form to do so or just send an email.

Change history:

- 2025-10-06: Under 6) 4th revision of the Manuals on borderline and classification for medical devices under Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices added

- 2025-04-10: Under 6) 4th revision of the MDCG 2020-16 and the statement from Team NB added

- 2024-10-10: Under 1c) reference to MDCG 2024-11 added; editorial changes

- 2024-03-08: Chapter on qualification of IVDs added; chart on conformity assessment procedures updated

- 2024-01-25: Link to EU reference laboratories added

- 2023-12-04: Complete revision of the article

- 2023-02-28: Adjustments regarding valid IVDR; link to guidance document MDCG 2020-16 rev.2 added; addition to Borderline Manual 2022

- 2022-07-11: Link to class D Common Specifications added

- 2022-03-04: Under 2d) reference to MDCG 2022-3 added

- 2022-01-28: Link to guidance document MDCG 2020-16 rev.1 added