Medical device cybersecurity is a focus not only for the FDA but also for other legislators and authorities, both in the US and other markets.

This is understandable

- because, on the one hand, cybersecurity threats are constantly increasing, and

- on the other hand, medical devices are becoming increasingly networked and, therefore, more vulnerable.

- In addition, patient care, such as diagnosis and therapy, is increasingly dependent on these networked devices.

The USA has added requirements for cyber devices to the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FD&C), and the FDA has published several guidance documents on cybersecurity, which are presented in this article.

1. FDA guidance on premarket cybersecurity

The first document, “Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submission,” is 57 pages long and was released in September 2023. However, the FDA has already planned an update in March 2024 (see chapter 1.4, “planned updates”).

You can download the FDA guidance on premarket cybersecurity here.

1.1 Requirements for the product life cycle

A central requirement of the FDA is that the manufacturer must have cybersecurity anchored in the QM system. To this end, it describes a Security Product Development Framework SPDF.

The FDA cites other valuable sources for understanding the SPDF:

- the Joint Security Plan (version 2 published in March 2024)

- the IEC 81001-5-1

1.1.1 Objectives of the SPDF

This SPDF must cover the entire product life cycle and achieve the “usual” objectives of IT security: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. The FDA supplements these “CIA objectives” with the capability of the device and system to be updated or patched quickly.

1.1.2 Activities required by the SPDF

The FDA wants manufacturers to achieve cybersecurity for their devices by carrying out “security risk management.” To this end, it refers to the AAMI TIR 57.

As part of this process, manufacturers must carry out the following activities:

- A threat modeling of the entire system, which requires a system architecture

- An assessment of the cybersecurity risks

- An assessment of the risks posed by interoperability (the FDA refers to the guidance document on interoperability)

- An assessment of the risks posed by off-the-shelf software and the creation of a software bill of materials SBOM (more on this in the article on SBOM)

- An assessment of the security risks posed by remaining “anomalies”

- An ongoing assessment of cybersecurity risks in the post-market phase. These can change, for example, because new attack vectors become known or devices are no longer maintained.

- This also includes monitoring the “Known Exploited Vulnerability Catalogs.”

- Cybersecurity testing that checks the effectiveness of measures to minimize cybersecurity risks and includes, for example, penetration and fuzz testing, static and dynamic code analysis, and attack surface analysis

1.2 Requirements for the device

The FDA also lists specific product requirements related to cybersecurity in the Annex. These relate to cryptography, authentication, authorization concepts, and the capability to log attacks and patch the device.

1.3 Requirements for the documentation

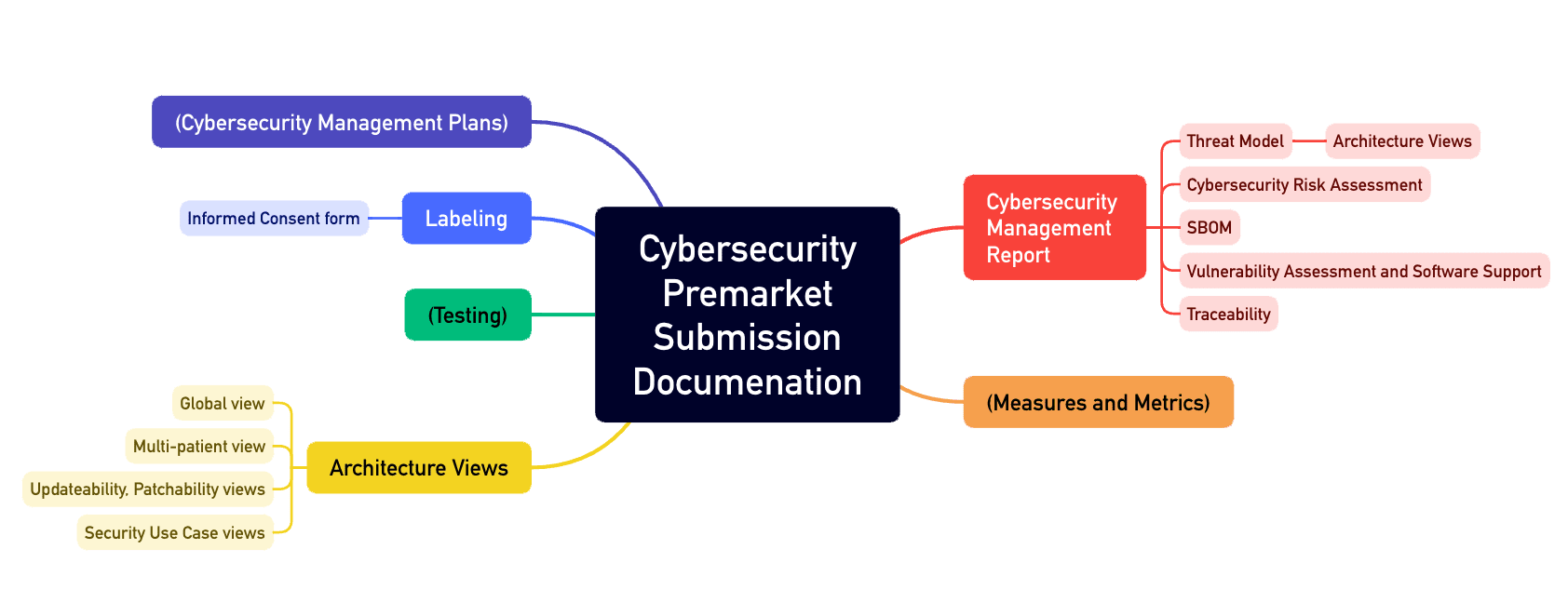

All of these activities must result in comprehensive documentation, such as:

- A cybersecurity management plan

- Architecture documentation with various views, such as the “Multi-Patient Harm View” and the “Updateability and Patchability View”

- SBOM

- Accompanying materials and instructions for use

The FDA even regulates the publication of “Security Issues” and refers to a NEMA requirement entitled “Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security.”

Annex 4 of the guidance document describes the structure of such a cybersecurity file (see Fig. 1).

1.4 Planned update

After just over six months, the FDA sees the need to amend the document. It has published these planned changes in a draft. One reason is the amended FD&C with Section 524b.

1.4.1 Change in the definition

The FDA is now more specific about what it counts as a cyber device: Even a USB port or serial interface would establish the device’s capability to connect to the Internet. Consequently, the requirements of Section 524B of the FD&C would have to apply and, thus, the FDA’s requirements for cybersecurity of medical devices.

1.4.2 Extended cybersecurity management plan

The FDA also wants an even more granular cybersecurity management plan:

- It should include a detailed description of how the manufacturer develops, releases, and rolls out patches.

- It also regulates even more precisely how manufacturers must disclose vulnerabilities and “exploits.”

- Finally, the plan, which must be maintained over the entire life-cycle, should differentiate between devices that continue to be maintained and those that have been discontinued but are still in use.

1.4.3 Changes to change notifications

The planned expansion of the guidance document on premarket cybersecurity also affects the change notifications to the FDA. The authority wants to see which parts of the device are being changed that could or should impact cybersecurity. Examples include the architecture, encryption algorithms, and new “connectivity features.”

1.4.4 Other changes

In the future, cybersecurity will also be relevant for the FDA when deciding whether a device is “substantially equivalent.” This means manufacturers must explicitly consider cybersecurity when specifying a “predicate device.”

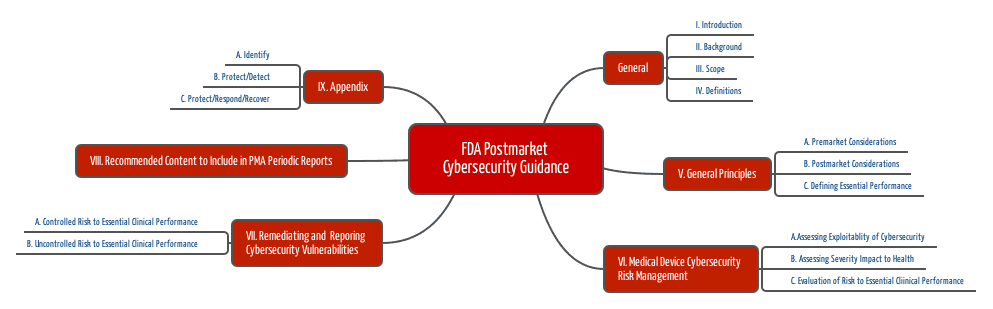

2. Post-market management of cybersecurity

A second guideline entitled “Post-Market Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices” from 2016 is clearly outdated.

You can download this “Post-Market Cybersecurity Guidance” here.

The FDA recognizes that manufacturers cannot predict and address all future cybersecurity-related threats during development. Therefore, manufacturers must continuously analyze these threats and act appropriately even after development.

The requirements of the premarket guidance document also contain requirements for post-market cybersecurity.

2.1 “Post-market” information sources

The sources of information that manufacturers should evaluate include:

- Output from security researchers

- Own tests

- Software and hardware suppliers

- Customers such as hospitals

- Institutions that specialize in collecting, analyzing, and disseminating relevant information

2.2 Measures

The FDA recommends using the NIST Framework (National Institute for Standards and Technology), whose elements (Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover) are also included in the first guidance document.

- Find out which essential (clinical) performance characteristics your medical device must fulfill.

- Identify the risks that occur if these performance characteristics are not met – in this case, due to a cybersecurity problem.

- Analyze how this problem can occur. Benefit from the information above.

- Evaluate these potential problems and their probabilities, e.g., using the Common Vulnerability Scoring System.

- Analyze the impact on health, i.e., the severity of possible harm.

- Assess the justifiability of the risks.

- Eliminate vulnerabilities (always), ensure the effectiveness of the measures, and document all this.

- Inform the users.

At this point, the FDA mentions that proactive measures to improve cybersecurity in accordance with 21 CFR part 806.10 do not have to be reported to the FDA.

2.3 Interim conclusion

The FDA’s requirements concretize what one would expect from standard market surveillance. Remarkable aspects are:

- The document is surprisingly specific in some places, e.g., regarding the sources of information to be evaluated or the methods to be used.

- The document answers when cybersecurity-related measures are to be reported.

- The document defines terms (e.g., exploit, remediation, threat, threat modeling) and gives numerous examples.

3. Significant differences to Europe

3.1 Life cycle phases

The FDA wants to see the post-market requirements mapped in a manufacturer’s plan (“Cyber Management Plan“). Interestingly, these requirements are set out in the premarket guidance document.

In Europe, on the other hand, harmonization of IEC 81001-5-1 means that the QM system is expected to fully map all pre- and post-market processes.

3.2 Documentation

The FDA is much more precise about the requirement for an SBOM: While IEC 81001-5-1 and the MDCG 2019-16 may at best mention the SBOM, the FDA links to the NTIA specification and adds further requirements (e.g., specification of the end of support for each element of the SBOM).

The FDA attaches great importance to the “architectural views” and precisely specifies its expectations.

3.3 Other

In addition, the FDA expects metrics to assess the manufacturer’s responsiveness to known vulnerabilities.

With the specific list of artifacts for submission and the statement that the term “cyber device” may refer to all data interfaces (explicitly including USB), the FDA is also very clear with its expectations. With MDCG 2019-16 and IEC 81001-5-1, the EU leaves much more room for interpretation.

4. Tips for manufacturers

The Johner Institute’s experience shows that manufacturers benefit from the following tips:

- Use the eStar format. This format lists the specific cybersecurity artifacts the FDA expects when submitting to all approval procedures (including PMA).

- Note that even purely local interfaces (e.g., USB or Bluetooth) require complete cybersecurity documentation. However, it is possible to scale the scope of this documentation.

- If anything is unclear, make use of “pre-submission meetings” with the FDA. The authority is often surprisingly helpful and open to discussion.

- Take advantage of our help, especially if you have little experience with the topic. The self-study route is usually time-consuming and error-prone.

- Have penetration tests carried out externally (e.g., by us) to avoid risking discussions about the independence of the testers. You should at least have the final software configuration tested. As we almost always find vulnerabilities in the process, we recommend smaller pen tests during development.

- Threat modeling is also very complex and time-consuming and requires much experience with security risks. We therefore recommend using tools and involving experts here, too.

5. Conclusion and summary

Medical devices that contain software or are software usually have data interfaces. They must, therefore, be designed to be sufficiently cyber-secure.

The FDA describes its requirements in great detail in its two guidance documents for pre- and post-market. It also provides practical assistance for implementation in the form of the Recognized Consensus Standards.

It is pleasing that this list also mentions IEC 81001-5-1, as this standard is already mandatory (e.g., Japan) or harmonized (in progress in the EU) in other parts of the world.

With the latest planned amendment to the premarket guidance, the FDA is raising the bar even higher. Now, manufacturers will also face cybersecurity requirements when making changes to devices that have already been approved.

Benefit from the Johner Institute’s help interpreting and efficiently implementing FDA requirements.

Don’t hesitate to contact the Johner Institute’s IT security experts.

Change history

- 2024-03-26: Article completely rewritten except the second chapter

- 2018-10-23: First version of the article published