On September 14, 2024, the new version of the German Health Interoperability Governance Regulation (or IOP Governance Regulation, or GIGV for short) came into force. The German Ministry of Health published a draft bill (only available in German) containing the recitals on April 24 of that year.

This version of the GIGV will replace the October 2021 version.

This article explains what the regulation requires and whether it affects you.

1. Background to the IOP Governance Regulation (GIGV)

a) Interoperability in healthcare

The healthcare system suffers from a lack of process consistency. This leads, for example, to

- higher costs, e.g., due to repeated examinations

- delays, e.g., due to redundant data entries, and

- risks for patients, e.g., due to incomplete or contradictory data

A necessary but insufficient condition for integrated (i.e., cross-sectoral) processes is the interoperability (IOP) of the products and systems used in healthcare. Interoperability is the ability of a system (e.g., a medical device or software) to work with other systems.

This short article on interoperability introduces an interoperability model. The classification into different levels helps to understand the differences between semantic and syntactic standards.

b) Problems the GIGV aims to solve

In the meantime, there are numerous interoperability standards. gematik, a part of the Germany ministry for health, published a vast number of these standards in the Vesta directory.

Based on the Health IT Interoperability Governance Regulation and the GIGV regulation that came into force in October 2021, the Vesta directory became the Interoperability Navigator INA for digital medicine (source, only available in German).

But that alone does not solve the interoperability problem:

- Problem 1: Lack of agreement on which standard to use

If there are several or even too many standards for a use case, this hinders interoperability. A prerequisite for homogeneity is that the providers of the information systems agree on a few standards. - Problem 2: Standards are not unambiguous

Many standards deliberately leave room for interpretation. For example, implementers can decide for themselves which data is mandatory and which is not. Syntactical standards make it possible to integrate different semantic standards. There is no “standardization of standards.”

The use of so-called “profiles” can help to limit the degree of freedom. However, it is particularly difficult for lay persons to recognize the degree of granularity of the interoperability standards and to understand whether it is suitable for the respective application. - Problem 3: Standards are not complete

Every new use case, every new business model, and every new type of data source (e.g., medical devices, apps) increases the probability that the appropriate interoperability standards are missing. There is currently no one who has a complete overview of the requirements and prioritizes the development of new standards.

The IOP Governance Regulation (GIGV) was intended to solve these problems. However, it has not been successful in the first attempt. The draft bill for the amendment (only available in German) states:

Despite the new structures and processes that have already been established, it has not been possible to prevent conflicting specifications from being developed or specifications that have been developed multiple times. This requires holistic and cross-sector coordination and orchestration of the interoperability process.

2. Proposed solution of the IOP Governance Implementation Regulation (GIGV)

Even if it is not clearly stated, the legislator – specifically the German Ministry of Health (BMG) – wants to use the GIGV to curb the proliferation of interoperability standards. To this end, a new position has been established at gematik:

The German Society for Telematics in Health Care maintains a competence center for interoperability in health care (competence center)

Translated from GIGV § 2(1)

a) Tasks of the coordination center

The task of this coordination center is to

- determine which interoperability standards are required,

- prioritize these needs,

- continuously specify requirements for new interoperability standards,

- recommend specific standards (or make them mandatory), and

- publish these standards on a knowledge platform.

In the October 2024 edition of the GIGV, the coordination center is also responsible for a conformity assessment procedure:

The creation of a standard conformity assessment procedure is intended to ensure that the requirements defined by the Federal Ministry as binding in the process are implemented by the manufacturers and that the relevant requirements are put into practice, thus having a concrete effect on the care of the population. The competence center, therefore, significantly contributes to more stringent and cross-sectoral interoperability governance in the healthcare system. The competence center is a central player responsible for promoting interoperability.

This conformity assessment procedure is described in § 13 of the regulation. For more information, see section 2.d).

b) Interaction of the coordination center with the expert committee, expert group, and working groups

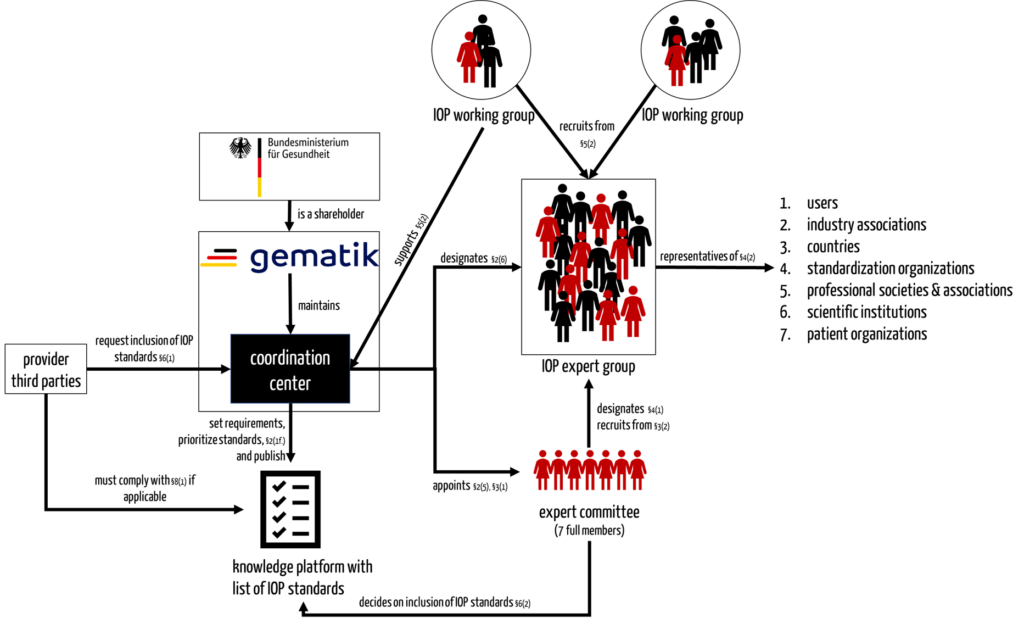

The IOP Governance Regulation (GIGV) stipulates that the coordination centers use several groups of people:

- Expert committee

The coordination center appoints an expert committee. This is composed of representatives of an IOP expert group. In addition, gematik and the BMG may each designate one extraordinary member. The expert committee decides, among other things, on including IOP standards in the knowledge platform. - IOP expert group

Experts are accepted into the IOP expert group representing various interest groups (see Fig. 1). Only people from this group can join the expert committee or become members of one of the working groups.

Ultimately, the IOP expert group is a group of people who are only able to act and make decisions as members of the expert committee or the IOP working groups. - IOP working groups

The coordination center sets up topic-related IOP working groups that are staffed by members of the expert group. The working groups support the coordination center in fulfilling its actual task (see 2.a).

c) Interaction of the coordination center with other stakeholders

For external stakeholders, there are at least two ways to interact at least indirectly with the new construct of coordination center, expert committee, and IOP working groups:

- They can propose experts for inclusion in the pool of the IOP expert committee through associations.

- They can request the coordination center to add new IOP standards to the list of IOP standards on the knowledge platform.

d) Obligation of manufacturers

Establish conformity with IOP standards

While § 11 of the GIGV (“Recommendation for Information Technology Systems in Healthcare”) still speaks of a “recommendation,” § 13 is more explicit.

(1) Manufacturers of information technology systems used in the healthcare sector for processing personal patient data must undergo the conformity assessment procedure at the competence center and have it certified that the respective information technology system meets the requirements in Appendix 1.

This has broadened the scope of application. The old version of the GIGV stated:

Health information technology systems used in the provision of health care services or that are fully or partially financed by public funds from the Federal Ministry of Health are to be designed in such a way that the recommendations included in the knowledge platform in accordance with § 10 and based on § 7 are fully implemented within 24 months of the recommendation.

Translated from GIGV § 8(1)

This means that medical information systems, DiGA (digital healthcare applications), and certain medical device manufacturers must design the data interfaces of their products in accordance with the defined IOP standards. This affects, for example, manufacturers of Hospital Information Systems (HIS), Patient Data Management Systems (PDMS), Practice Information Systems (PIS), and Radiology Information Systems (RIS).

Undergo the conformity assessment procedure

The IOP Governance Regulation defines the conformity assessment procedure in § 13. (Not to be confused with conformity assessment procedures defined by MDR/IVDR.) The Annex I referenced there deals with requirements from the “Implementation Guide for Primary Systems – Electronic Patient Record (EPR).”

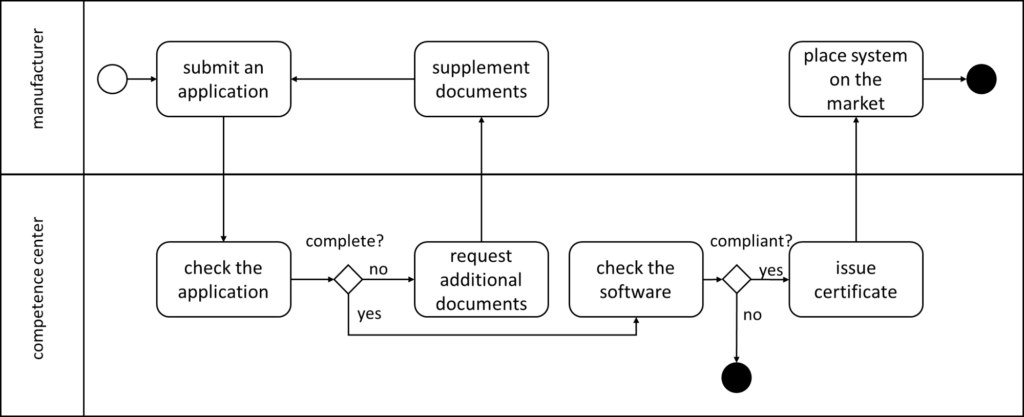

In the first step, manufacturers must submit an application. The GIGV defines the contents of this application in § 13 (2). This must include, for example, master data on the manufacturer and the software, as well as explanations and test reports.

The GIGV does not specify how, i.e., with which methods and tools, the competence center conducts the inspections. It leaves this to the “rules of procedure” of the competence center in accordance with § 18. The regulation only specifies a deadline – for the manufacturers, not the competence center.

The competence center requests missing information or documents as a supplementary request. The application supplement must be submitted within three months of receipt of the supplementary request. Otherwise, the competence center will reject the application.

If the application is successful, the competence center issues a certificate to the applicant.

3. Evaluation of the IOP Governance Regulation (GIGV)

It is obviously still too early to evaluate the new GIGV. Nevertheless, initial conclusions can be drawn.

a) What seems sensible

It is obvious that there is currently a confusing variety of interoperability standards. Simply listing these standards in a directory is not enough to ensure sufficient interoperability.

Therefore, the desire for a guiding hand seems understandable.

b) Where there are still question marks

Nevertheless, the new regulation can also cause a good deal of concern:

- Dominance of the German Ministry of Health

The GIGV follows the trend of the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) to issue new regulatory requirements at short intervals and to concentrate more and more power on itself. The GIGV leaves no doubt that it will determine the IOP standards. The argument that independent experts would do this does not hold water because the coordinating body decides on all committee and working group appointments. - The expertise of the experts

It remains unclear which criteria will be used to select the experts; it is clear that the numerical distribution of various interest groups will play a role. While the optimism of representatives of standardization organizations (one example would be HL7) is well founded, it remains to be seen which experts patient organizations and the countries want to and can appoint. Is interoperability country-specific?

This also raises the question of the composition of the expert committee. The designation of a representative from each stakeholder group may seem democratic, but the manufacturers are the ones most affected by the definition of interoperability standards. And then, is a single person supposed to represent medical technology companies, IT manufacturers, and DiGA startups equally? The MDR has painfully demonstrated how well (or poorly) this works. - Legal uncertainty

A law that requires an inspection but does not specify the specific criteria that will be checked or the methods of this inspection leads to uncertainty. The fact that the law sets deadlines for manufacturers (e.g. submission of information, duration of certificates), but not for the competence center, may lead some to question the mindset of the legislator. - Overhead

It is obvious that the new governance regulation means additional work not only for gematik. In particular, the manufacturers mentioned in § 13 are affected. The regulation states:

“For industry, this may result in unquantifiable costs for adapting products to common standards.”

Some manufacturers may already perceive this as cynicism. It should be clear to everyone that a (legally enforced) change to a data interface constitutes a significant design change, according to MDCG 2020-3. - No evidence specification

The GIGV does not reveal what evidence it is based on. Where is the benefit-risk assessment? Where does the assumption come from that the objectives will be achieved in the second attempt without unnecessarily burdening manufacturers? Which metrics will be used to determine the hoped-for efficiency gains in healthcare?

The FDA is showing us how regulatory science can be used to achieve success with evidence-based regulation. Wouldn’t that be a suggestion? The Johner Institute research team would be happy to help.

4. Conclusion

Unnoticed by many, the German Ministry of Health has revised the IOP Governance Regulation (GIGV) and added an obligation for a conformity assessment procedure. It would be a mistake to hope this regulation would only affect state institutions. Instead, this regulation also affects many manufacturers of medical devices (e.g., DiGA) and medical information systems through new bureaucratic and additional efforts for development and regulatory affairs.

It remains to hope that the benefits of the new regulation will outweigh the disadvantages. It would have been better if one had not had to hope for it but had already had evidence.

Regulatory science is a branch of research that aims to formulate regulatory requirements based on evidence-based knowledge. Research is being conducted at the Johner Institute, among others.

Change history:

- 2024-10-03: Due to revision of the regulation, many editorial changes have been made and requirements for manufacturers, including a new figure added in chapter 2.d)

- 2023-04-19: Note added that the Vesta directory has been transferred to the “Interoperability Navigator INA”

- 2021-09-21: First version of the article published