Manufacturers must demonstrate the biological safety and, thus, the biocompatibility of their medical devices. The ISO 10993 family of standards helps them to do this.

Content

This page provides an overview regarding:

- Biological safety and biocompatibility: Examples, definitions

- Regulatory requirements for biological safety

- Approaches to achieving biological safety / biocompatibility

- Demonstrate biological safety / biocompatibility (relevance of tests)

- Support for medical device manufacturers

1. Biological safety and biocompatibility

1.1 Examples

1.1.1 Examples of biological hazards and risks

Medical devices that come into physical contact with patients, in particular, carry biological risks that may be caused by:

- Chemicals that leach out of medical device materials, are absorbed into the body, and have harmful effects on health

- Implants that cause a rejection reaction

- Materials that trigger an allergic reaction

- Materials that are broken down or transformed by the body contrary to the intention of the manufacturer

- Implants and materials that do not grow into the body as desired

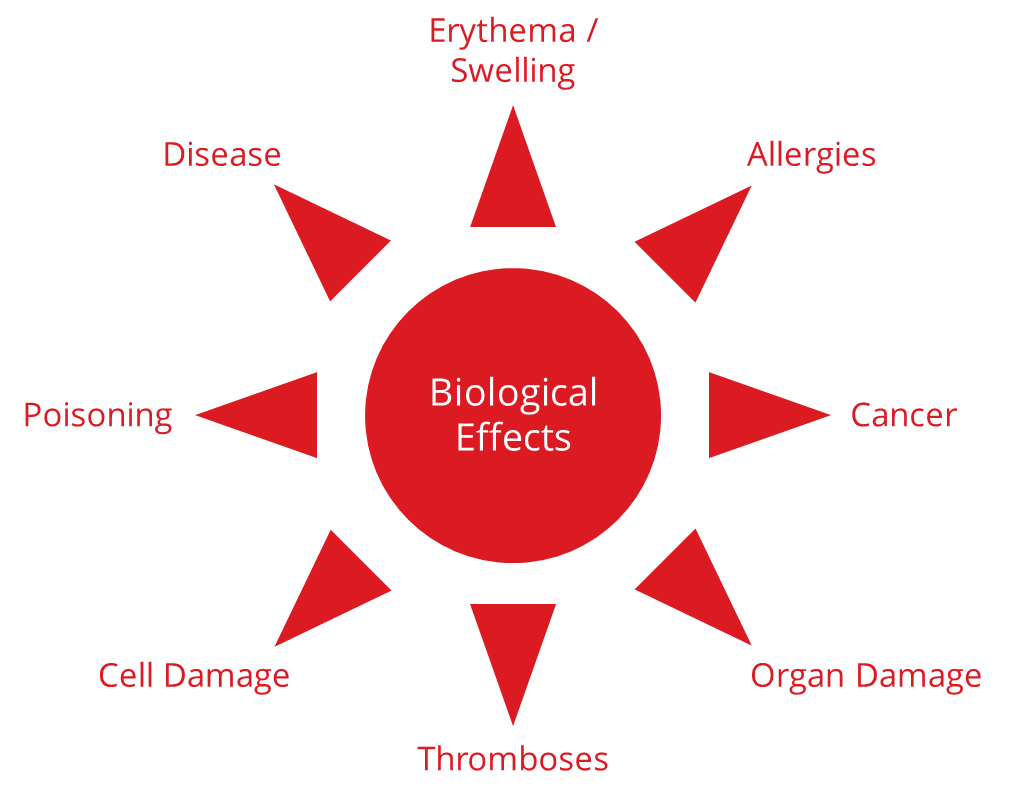

1.1.2 Examples of harm

These risks can lead to a variety of harms:

- Erythema, swelling, localized inflammation

- Allergies

- Fever

- Systemic toxicity, e.g., organ damage, poisoning

- Cancer

Fig. 1: Examples of the harm caused by a lack of biological safety

1.2 Definitions

1.2.1 Biological Risk

ISO 10993-1 defines the term biological risk as follows:

“combination of the probability of occurrence of biological harm and the severity of that biological harm”

Source: ISO 10993-1:2025

1.2.2 Biological Safety

Thus, biological safety promises freedom from unacceptable biological risks in the context of intended use.

Biocompatibility

The definition of the term “biocompatibility” is slightly more cryptic:

“ability of a medical device or material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application”

Source: ISO 10993-1:2025

The term host response here refers to potential undesirable adverse reactions. The standard states that biocompatibility can be demonstrated through biological testing and an evaluation of the leachables.

In the biological risk assessment according to ISO 10993-1, biological safety is assessed by considering the biological risks associated with:

- the components of a medical device and

- the interactions between the device and tissue

The biological risks associated with infectious agents do not fall within the scope of ISO 10993!

1.3 Endpoints of biological safety according to ISO 10993

Manufacturers must ensure their medical devices’ biocompatibility and minimize the likelihood of harm due to a lack of biological safety.

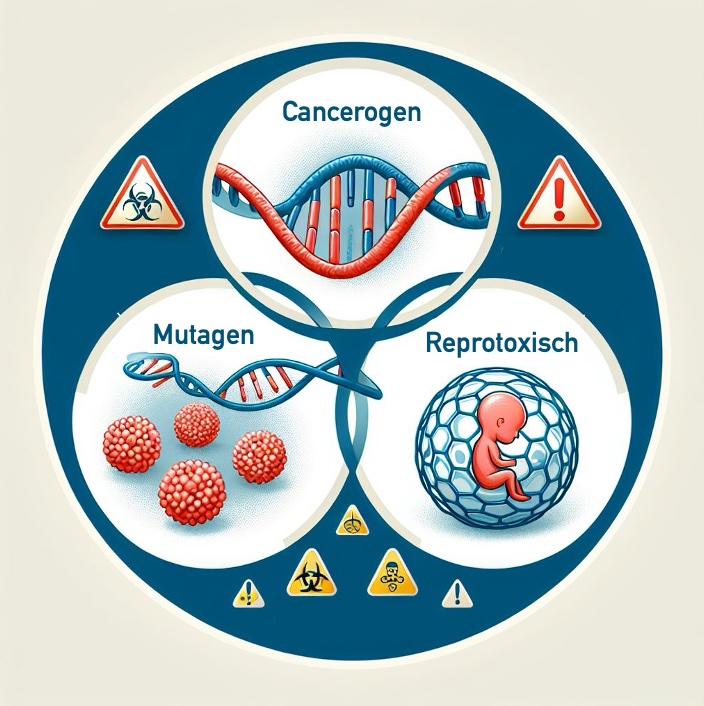

The specific (negative) biological effects that manufacturers have to assess in the biological evaluation are called endpoints. Examples of endpoints are:

- Cytotoxicity (cell damage)

- Skin sensitization (e.g., allergic reaction)

- Irritation of the skin or tissue (e.g., erythema and itching)

- Systemic toxicity: acute, subacute, subchronic, and chronic toxicity (e.g., organ damage, death)

- Material-related pyrogenicity (causing fever)

- Genotoxicity (damage to DNA)

- Carcinogenicity (causing cancer)

- Reproductive toxicity (impairment of fertility)

- Implantation effects (e.g., implant rejection)

- Blood incompatibility (e.g., thrombosis)

Sections 4 and 5 of the article describe how manufacturers can achieve and test biological safety.

2. Regulatory requirements

2.1 MDR requirements

The Medical Device Regulation (MDR) requires the biocompatibility of medical devices at several points:

Annex I: General safety and performance requirements

Annex I of the MDR does not explicitly mention the term biocompatibility. However, it does state:

Devices shall be designed, manufactured and packaged in such a way as to minimise the risk posed by contaminants and residues to patients, taking account of the intended purpose of the device, and to the persons involved in the transport, storage and use of the devices. Particular attention shall be paid to tissues exposed to those contaminants and residues and to the duration and frequency of exposure.

MDR, Annex I, Section 10.1

In the very first section of Annex I, the MDR demands that the safety and health of patients, users and third parties are not compromised and that manufacturers must “eliminate or reduce risks as far as possible through safe design and manufacture”.

Annex II: Technical documentation

In Annex II, the MDR requires manufacturers to document information on all tests, including the

“test design, complete test or study protocols, methods of data analysis […] test conclusions regarding in particular the biocompatibility of the device including the identification of all materials in direct or indirect contact with the patient or user [as well as regarding the…] physical, chemical and microbiological characterisation;”

MDR, Annex II, Section 6.1.b)

The MDR also regulates the case that the manufacturers do not carry out tests:

Where no new testing has been undertaken, the documentation shall incorporate a rationale for that decision. An example of such a rationale would be that biocompatibility testing on identical materials was conducted when those materials were incorporated in a previous version of the device that has been legally placed on the market or put into service;

MDR, Annex II, Section 6.1.b)

Annex VII: Requirements for notified bodies

This annex affects manufacturers indirectly at least, because in it the MDR requires notified bodies to:

- Guarantee the competence of the notified body staff with regard to biocompatibility

- Up-to-date knowledge of the manufacturer

Notified bodies must check a manufacturer’s processes designed to ensure that the manufacturer is using the latest scientific knowledge, including with regard to the biocompatibility of materials.

2.2 FDA requirements

2.2.1 ISO 10993 as Recognized Consensus Standards

The FDA also expects medical devices to be biocompatible. It recognizes the ISO 10993 family of standards as Recognized Consensus Standards.

2.2.2 Guidance Document for ISO 10993-1

In addition, the FDA has published a detailed guidance document on ISO 10993-1 to evaluate biocompatibility. In it, the FDA describes the procedure according to ISO 10993-1 in detail and additional requirements, such as further endpoints for certain device categories. The missing endpoints in ISO 10993-1 are one reason why the FDA only partially recognizes ISO 10993-1:2018. The new version of ISO 10993-1:2025 is state of the art, but has not yet been evaluated by the FDA.

2.2.3 Guidance Document on biocompatibility evidence without animal testing

Annex G “Biocompatibility of Certain Devices in Contact with Intact Skin“ was added to the version of the document published in 2023 to support further the “3Rs approach” of reduction, refinement, and replacement of animal testing.

2.2.4 Draft of the guidance document on chemical analysis and ISO 10993-18

In September 2024, the FDA also published a new draft of a guidance document on biocompatibility that specifically addresses the performance of chemical analyses.

- Objective: The objective of the document is to standardize the procedure. It thus narrows the leeway that the standard allows.

- Focus: The focus of the guidance is on extractable studies, i.e., the identification and quantification of substances that are released into solvents after extraction of the medical device.

- Content: The guidance offers detailed recommendations for performing the extraction, chemical analysis, and the necessity of comprehensive and precise documentation – in addition to ISO 10993-18.

- Target audience: The document is primarily aimed at toxicologists, biocompatibility evaluators, and experts in toxicological risk evaluations, but above all, at laboratories that carry out chemical analyses.

- Criticism: It should be noted that the requirements for the scope of chemical analysis, data quality, and, in particular, documentation are very high. This increases product safety but could result in an disproportionate increase in the effort and cost of laboratory testing, even for proven standard materials.

Conclusion: The requirements for biocompatibility are increasing. It is, therefore, important to select and carry out laboratory tests in a very targeted manner.

2.3 The requirements of the ISO 10993 family of standards

2.3.1 Overview of the family of standards

The 10993 family of standards for the “Biological safety of medical devices” consists of several parts, some of which are harmonized under the MDR. The harmonization of standards is an ongoing process, so the status changes. It is recommended that the official publications of the European Commission and the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) be regularly consulted to review the current status of the harmonized standards.

| Standard |

Title |

Harmonized under MDR? |

| ISO 10993-1 |

Evaluation of the biological safety within a risk management process |

No |

| ISO 10993-2 |

Animal welfare requirements |

No |

| ISO 10993-3 |

Tests for genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and reproductive toxicity |

No |

| ISO 10993-4 |

Selection of tests for interactions with blood |

No |

| ISO 10993-5 |

Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity |

No |

| ISO 10993-6 |

Tests for local effects after implantation |

No |

| ISO 10993-7 |

Ethylene oxide sterilization residuals |

No |

| ISO 10993-9 |

Framework for identification and quantification of potential |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-10 |

Tests for skin sensitization |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-11 |

Tests for systemic toxicity |

No |

| ISO 10993-12 |

Sample preparation and reference materials |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-13 |

Identification and quantification of degradation products from polymeric medical devices |

No |

| ISO 10993-14 |

Identification and quantification of degradation products from ceramics |

No |

| ISO 10993-15 |

Identification and quantification of degradation products from metals and alloys |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-16 |

Toxicokinetic study design for degradation products and leachables |

No |

| ISO 10993-17 |

Toxicological risk assessment of medical device constituents |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-18 |

Chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process |

Yes |

| ISO 10993-19 |

Physico-chemical, morphological and topographical characterization of materials |

No |

| ISO 10993-20 |

Principles and methods for immunotoxicology testing of medical devices |

No |

| ISO 10993-23 |

Tests for irritation |

Yes |

2.3.2 The general standard ISO 10993-1

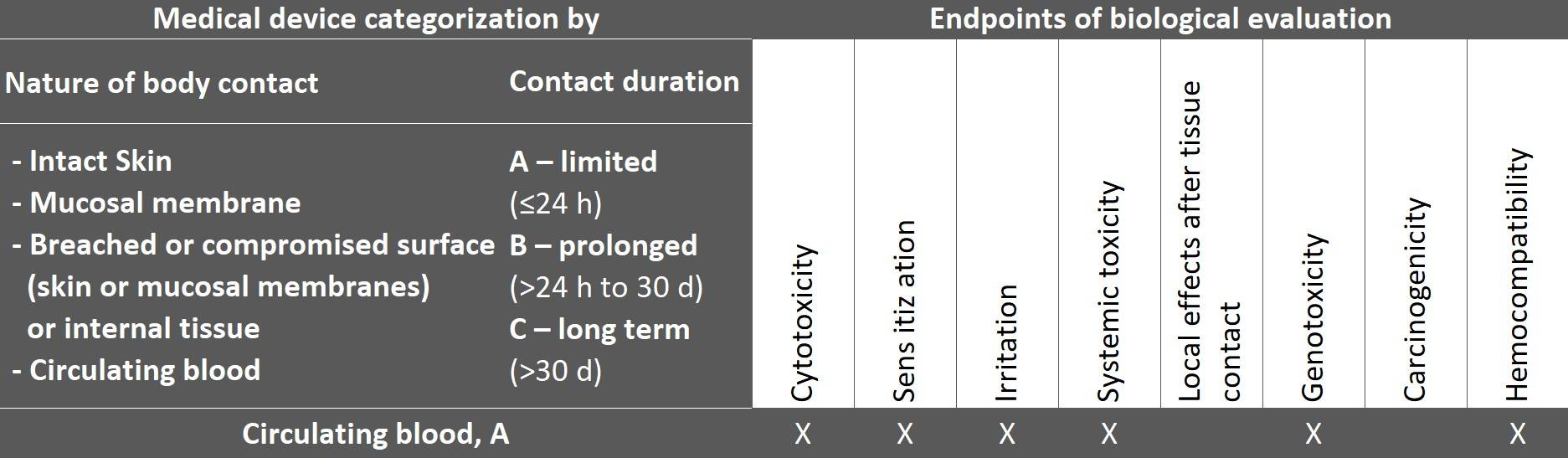

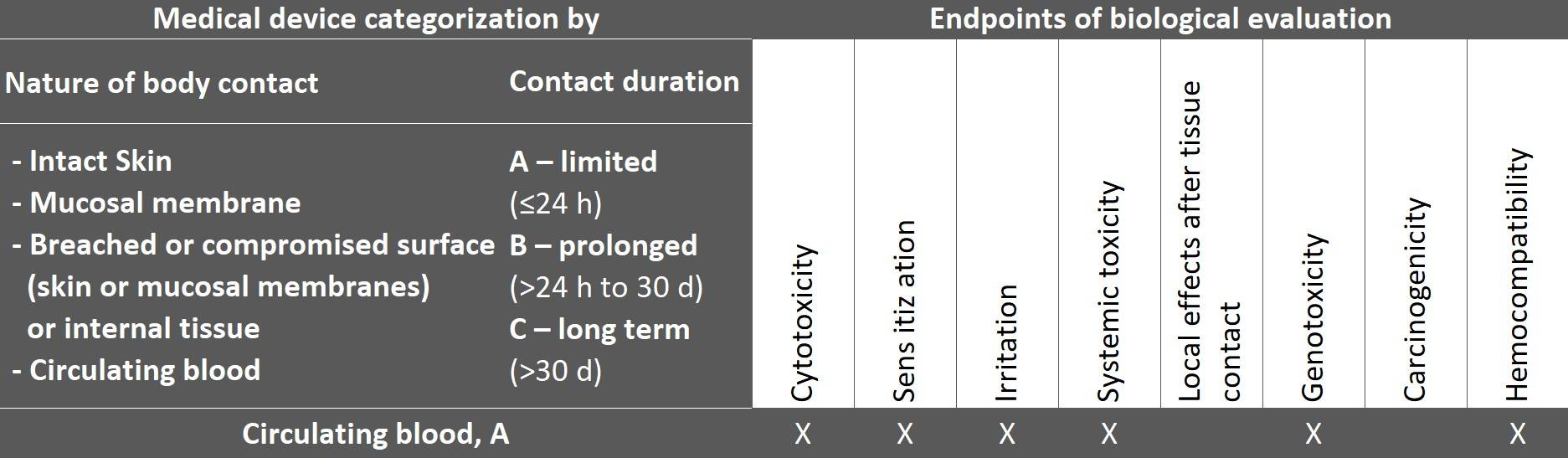

The general standard ISO 10993-1 also determines the endpoints (biological effects) according to the product categorization by type of contact and duration, which manufacturers must address when evaluating biological safety.

The following excerpt from the table shows the endpoints for a medical device that comes into contact with circulating blood.

Fig. 2: Taken from ISO 10993-1:2025, table 4

The table is not a checklist for tests but rather provides guidance on which endpoints should be evaluated for the device category.

It is also important to note that ISO 10993-1 explicitly requires material characterization and that animal testing should be avoided. In addition, material characterization provides more meaningful information and, thus, a higher level of biological safety.

ISO 10993-1 makes it clear that manufacturers must ensure biological safety over the entire life cycle of a medical device:

“The biological evaluation of a medical device shall consider its life cycle.“

ISO 10993-1:2025, 4.3

As part of the biological risk analysis, all characteristics and influences that are considered relevant to biological safety must be taken into account in order to meet the requirement for “freedom from unacceptable biological risks”. Chapter 6 of ISO 10993-1:2025 describes the procedure in detail. This includes the general procedure, the identification of safety-relevant characteristics, categorisation of the medical device according to type and duration of contact, description of biological effects, gap analysis and performance of necessary tests.

Examples of the most significant changes in the long-awaited version 2025 of ISO 10993-1 are:

- Requirement to create a plan (Biological Evaluation Plan – BEP)

- Risk-based approach and integration of risk management terminology (ISO 14971)

- Chemical characterization as the fundamental basis for biological evaluation

- Changes in product categories with regard to the biological effects (endpoints) to be addressed and calculation of the cumulative duration of use (daily use/intermittent use)

- Even more detailed requirements for the assessment of biological safety over the entire product life cycle

Manufacturers should therefore:

- Perform a gap analysis

- Create or revise a Biological Evaluation Plan

- Perform the necessary tests

- Create a (revised) Biological Evaluation Report

- Update or recreate a Toxicological Risk Assessment (TRA)

2.4 Further regulatory requirements

In addition to the ISO 10993 family of standards, manufacturers should also observe further regulatory requirements in addition to product-specific standards, such as:

3. Achieving biological safety

Achieving biological safety means minimizing biological risks. The MDR and ISO 14971 describe three types of risk-minimizing measures:

- Measures that create inherent safety

- Protection measures

- Measures in the form of information

Measures for biological safety are:

- Using high-quality materials that are suitable for the application

- Ensuring clean production

- Cleaning, disinfecting, and sterilizing devices using suitable procedures

- Avoiding contact with the device (e.g., by using protective equipment) or reducing contact (e.g., by shortening the duration of contact)

4. Demonstrate biological safety

4.1 Demonstration with a focus on medical devices

Manufacturers are obliged to assess the effectiveness of these measures and thus demonstrate biological safety and biocompatibility regarding the above-mentioned endpoints (where relevant).

The first step is to gather information for the verification process for the medical device to be evaluated.

- Material data sheets, such as safety data sheets for raw materials, technical data sheets for processing and suitability

- Certificates, e.g., regarding the biocompatibility of the purchased material

- Search results for known ingredients and additives

- Production aids used

- Market experience

CAUTION: The information is necessary and important but usually insufficient to prove the final device’s biocompatibility.

There are additional influences on the biocompatibility of the device that must be considered to evaluate all necessary endpoints:

- Processing of the material, e.g., polymerization

- Additives and colorants used in addition to the main ingredients

- Adhesive processes and interactions

- Laser engraving and labeling

- Final cleaning and chemicals used in the process

- Sterilization and material influence

- Packaging and storage

Fig. 3: ISO 10993 – Examples of factors influencing biocompatibility

CONCLUSION: Proof of biocompatibility cannot be provided exclusively based on data sheets for the material. Therefore, tests of the final device are usually necessary.

The ISO 10993 family of standards describes how the evidence should be presented. For example, after a well-planned chemical characterization according to ISO 10993-18, the toxicological evaluation according to ISO 10993-17 should be carried out under the worst conditions in terms of exposure. In doing so, manufacturers test the final device to ensure that it is free of biological hazards, such as toxicologically relevant substances (organic and/or inorganic).

When providing this evidence, manufacturers should avoid animal testing wherever possible. A risk-based and well-planned testing strategy and the definition of application-dependent test parameters are necessary to keep costs low and enable a successful toxicological evaluation of the results.

4.2 Demonstration with a focus on the processes

The biological safety of medical devices includes not only the biocompatibility of the materials used but also possible hazards from infectious microorganisms. To minimize biological risks from superficial contamination with pathogenic bacteria/viruses, for example, processes are introduced that must be validated.

This includes

- Reprocessing of the devices (according to ISO 17664)

- Final cleaning

- Sterilization

5. Support

Do you have any questions about biocompatibility or the ISO 10993 family of standards?

Please contact us, if you need support with the:

- Development of your biocompatible medical devices

- Creation of a biocompatibility test strategy, and selection of a testing laboratory, as well as organization of the necessary tests

- Biological Evaluation Plan (BEP) and Biological Evaluation Report (BER)

- Toxicological risk evaluation of the results in a Toxicological Risk Assessment (TRA)

- Validation of processes such as reprocessing, cleaning, and/or sterilization

- Creation of a lean and standards-compliant technical documentation

In this way, you ensure that you develop your devices quickly and safely and get them on the market without any problems during the approval process.

If you want to gain a deeper understanding of the subject, our Medical Device University offers a self-study course.

Change history

- 2025-12-18: Update of references and the categorization table in accordance with ISO 10993-1:2025

- 2025-11-28: In section 2.3, the changes introduced by version 2025 of ISO 10993-1 are described.