The term “predicate device” most often comes up in the context of FDA 510(k) clearances. However, the FDA does not define this term. It does, however, define what “substantial equivalence” is. Sounds complicated?

Demonstrating equivalence is by no means only relevant in the FDA context. That’s why this article provides clarity – especially but not only for manufacturers who want to market their medical devices in the USA.

1. Predicate device: The basics

a) What is a predicate device?

“Predicate device” is not a defined term. The FD&C-Act in Section 513(i) defines the term “substantial equivalence”:

(1) (A) For purposes of determinations of substantial equivalence under subsection (f) and section 360j(l) of this title, the term “substantially equivalent“ or “substantial equivalence“ means, with respect to a device being compared to a predicate device, that the device has the same intended use as the predicate device and that the Secretary by order has found that the device has […].

FD&C Section 513(i)

The full definition can be found below.

Accordingly, the predicate device serves as the comparative product used to demonstrate equivalence to a device that a manufacturer wishes to market in the US. The manufacturer makes the demonstration itself, and the FDA reviews this “substantial equivalence” as part of the premarket notification, better known as the 510(k) procedure.

In accordance with 21 CFR 807.92 (a) (3), a comparative product may be:

- A medical device legally marketed in the US prior to May 28, 1976 (i.e., prior to the implementation of risk-based classification): a “Pre-Amendment Device”

- A medical device legally marketed in the US that the FDA has assigned to class I or class II

- A medical device legally marketed in the US for which substantial equivalence has already been established via a 510(k) procedure

b) When or why is it necessary to make a determination?

A predicate device is required under the 510(k) procedure. This is the most common “approval” process in the US for class II devices, as well as certain class I and III devices. However, some class II devices are exempt from premarket notification (“exempt” status).

The FDA maintains a list of “exempt devices“ on its website.

In the 510(k) procedure, it is sufficient for the manufacturer to demonstrate equivalence with a predicate device. If this is successful, the FDA assumes that the device is at least as safe and effective and grants market clearance (510(k) clearance).

Without proof of equivalence, a costly and more complex De Novo or even PMA procedure must be applied. This leads to higher costs, higher requirements for evidence to be submitted (e.g., clinical data), and a longer approval time.

c) What is the difference with equivalent devices (MDR)?

Role of the equivalence approach

The MDR has a similar concept. It speaks of an “equivalent device” (see Article 61 MDR).

However, this comparison with an equivalent device is limited to the clinical evaluation and not to the entire conformity assessment procedure.

By providing evidence of similarity, it is possible under the MDR to use clinical data from the comparative product for one’s own clinical evaluation. In certain cases, this may even eliminate the need for a clinical investigation of high-risk devices (Article 61 (4) MDR).

Evaluation criteria

The evaluation criteria regarding equivalence between FDA and MDR are also different:

- The MDR distinguishes between technical, biological, and clinical.

- The FDA distinguishes between “intended use” and “technological characteristics.”

It can be said that the MDR is stricter concerning the MEDDEV 2.7/1 rev.4 in terms of demonstrating equivalence. For example, under the MDR, the use of identical materials is required, or identical indications and body regions. Here, the FDA is less strict.

There are successful 510(k) procedures in which the equivalence of software for assessing anomalies using image data with software for assessing and characterizing breast anomalies using MR image data has been successfully demonstrated and cleared by the FDA (source).

2. Determine a predicate device

a) Definition and algorithm

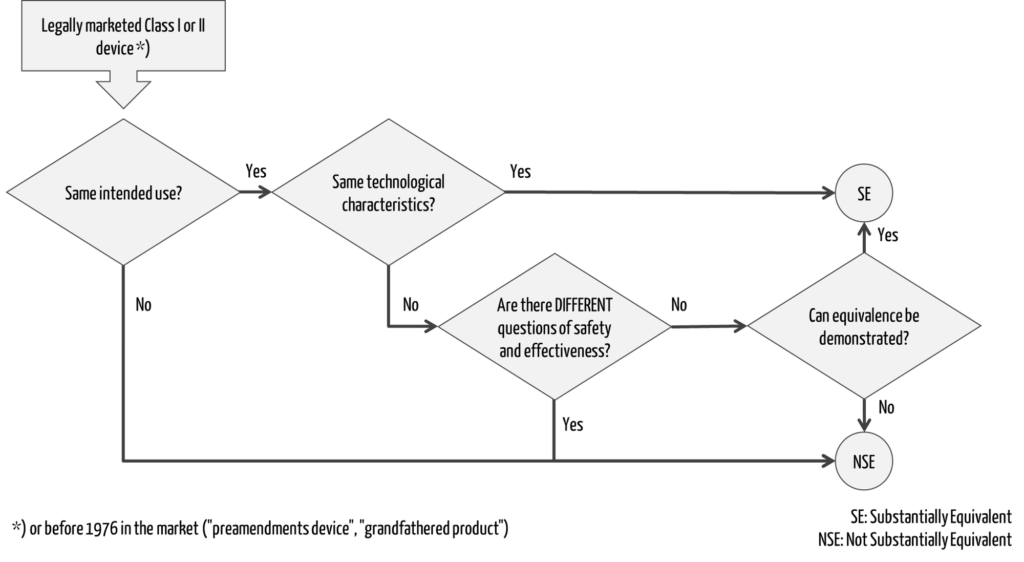

Section 513(i) of the FD&C Act determines when two devices may be considered “substantially equivalent.”

““substantial equivalence” means, with respect to a device being compared to a predicate device, that the device has the same intended use as the predicate device and that the Secretary by order has found that the device-

(i) has the same technological characteristics as the predicate device, or

(ii) (I) has different technological characteristics and the information submitted that the device is substantially equivalent to the predicate device contains information, including appropriate clinical or scientific data if deemed necessary by the Secretary or a person accredited under section 360m of this title, that demonstrates that the device is as safe and effective as a legally marketed device, and (II) does not raise different questions of safety and effectiveness than the predicate device.”

A decision tree can be used to determine whether a predicate device exists for a device, i.e., whether the second device is “substantially equivalent” as defined by the FDA (Fig. 1).

Must-read includes these three FDA guidances:

- The 510(k) Program: Evaluating Substantial Equivalence in Premarket Notifications [510(k)] (published 2014)

- Benefit-Risk Factors to Consider When Determining Substantial Equivalence in Premarket Notifications (510(k)) with Different Technological Characteristics (published 2018)

- Best Practices for Selecting a Predicate Device to Support a Premarket Notification [510(k)] Submission (Draft from September 07, 2023)

b) Criterion 1: Same intended use

First, manufacturers must demonstrate that the intended use is identical to that of the predicate device. In contrast to the MDR criteria for clinical evaluation, however, the FDA refers here to the overall medical purpose. Differences in indications, patient population, or users, therefore, do not necessarily lead to a new intended use.

In the example of software for assessing anomalies using image data, the manufacturer claims that a different body region and indication do not lead to a different intended use, which is the assessment of specific disease states using standard of care scoring using machine learning algorithms. The FDA agreed with this comparison.

c) Criterion 2: Technological characteristics

Identical technological characteristics will rarely exist. Otherwise, we would be stuck in an old state of the art. When the FDA talks about technological characteristics, this includes materials, energy sources, algorithms, or design in general.

Even if these are not identical, 510(k) clearance is possible. However, the differences in technology may not raise different (!) questions of safety or effectiveness.

By “different,” the FDA is referring specifically to safety and effectiveness issues that did not arise with the predicate device but do raise safety or effectiveness concerns with the subject device.

Example 1: A forehead thermometer is not a suitable predicate device for an ear thermometer. In the case of ear thermometers, questions arise, and risks exist with regard to biocompatibility. This is not the case with a forehead thermometer, which records body temperature without contact to the patient.

Example 2: An oropharyngeal tube for keeping the airway open is not a suitable predicate device for a non-invasive device that keeps the airway open by applying a vacuum to the neck from the outside. In the latter, continuous pressure is applied to tissues and nerve structures. This raises questions about the risks associated with nerve stimulation.

d) Criterion 3: Application of best practices

The FDA wants to modernize its outdated 510(k) procedure. To do so, it describes additional criteria for selecting an appropriate predicate device.

In the future, the FDA would like to better understand why manufacturers give priority to a particular predicate device from a selection of valid predicate devices. Manufacturers must justify their choice.

The following criteria should influence the selection:

- Application of well-established methods

The predicate device should have been cleared by the FDA using well-established methods. This includes specifications from current recognized consensus standards, current FDA guidance documents, or the use of Medical Device Development Tools (MDDTs). This indirectly means that manufacturers will no longer be able to compare their devices with (very) old predicate devices in the future. - Continuously meet or exceed safety and performance requirements

In the best case, medical devices achieve or exceed the level of safety and performance initially determined for clearance over their lifetime. Thus, devices are not suitable as predicate devices if, for example, there is a high frequency of reports of adverse events or incidents (death, injury, malfunction) that were not initially considered or an increase in the frequency or severity of the incidents. This could indicate fundamental problems with the design. - Unmitigated use- or design-related safety issues

Known safety issues with the predicate device, e.g., due to lack of usability or problematic design, should have been mitigated. - Design-related recalls

The predicate device should not have been recalled from the market due to design-related problems.

3. Find a predicate device

Step 1: Search FDA database

A good first step is to search the FDA 510(k) database for known similar devices (e.g., competitors) (by trade name, manufacturer name, or 510(k) number).

Step 2: Search in classification database

If you do not find what you are looking for here, or if there are no known similar devices, you may be successful using the classification database. Here, one first selects the correct product category (“product code”) and can then search for cleared devices in the 510(k) database.

Step 3: Evaluation against the criteria

Once potential predicate devices have been selected in this way, they must be evaluated against the above criteria. For this purpose, the manufacturers collect the following information:

- Intended use

Here, it is generally worth taking a look at the public summary of the 510(k), the “510(k) summary.” A look at the instructions for use (if available) or the manufacturer’s website is also helpful. - Technological characteristics

Information about basic technological characteristics can be found in the 510(k) summary, in the instructions for use, or via other publicly available information. Through the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA), it is possible to request complete 510(k) files from the FDA. However, this process can sometimes take over a year; in addition, confidential information is usually redacted. - Additional criteria

- Well-established methods: These should have been mentioned in the 510(k) summary. Sometimes, there are references to applied consensus standards in the instructions for use or labeling.

- Post-market information: Information on safety issues and recalls is publicly available through various FDA databases:

4. FAQ for predicate devices

Question 1: Does it have to be exactly one predicate device?

Ideally, one predicate device is sufficient for the demonstration of substantial equivalence. Sometimes, however, such a device cannot be found. In this case, it is also possible to use two or more devices as predicates. However, the FDA recommends labeling the most similar device as the “primary predicate device.”

Substantial equivalence must be demonstrated to all selected predicate devices. This means that the intended use must be identical over all predicates. Technologically, there may be differences, as explained above.

Example vital monitor: For a monitor for monitoring vital parameters, it would be conceivable to select individual predicate devices for specific vital parameters (e.g., body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate).

Question 2: What is the difference to a “reference device” (FDA)?

In addition to the predicate devices, the FDA also knows so-called “reference devices.” These can support a 510(k) submission or demonstration of substantial equivalence. However, they do not replace a predicate device.

For example, manufacturers may use a reference device to point FDA to devices that have a different intended use and thus are not suitable as a predicate device but use similar technological characteristics (e.g., materials) in a different context and have been successfully cleared.

The reference device supports the last question in the decision tree (Fig. 1) regarding the demonstration of equivalence (e.g., regarding the test method applied).

Question 3: How do you document equivalence?

The core element of a 510(k) file is a comparison table between the new device and the predicate. In this table, the manufacturer should list and discuss in detail similarities and differences concerning intended use, indications, and relevant technological characteristics. For each entry, there should be a rating of equivalence (e.g., “same,” “similar,” “different”).

In the case of differences, precise justifications should be given as to why these do not lead to different questions regarding safety and effectiveness. Manufacturers should be as specific as possible: For example, the use of the same methods (e.g., same standard applied) and the fulfillment of the same requirements (e.g., within the limits as stated in the standard) together with the corresponding evidence can serve as justification.

Manufacturers substantiate equivalence by providing further information on the methods used (see above) and the associated evidence. In general, the FDA accepts a least burdensome approach. This means, for example, that it waives the submission of full test reports in certain cases.

5. Tips

Tip 1: Do not split intended use

Since the FDA explicitly allows multiple predicate devices, it is tempting to split the intended use among multiple predicate devices. This will result in the FDA rejecting the argument that the device is “substantially equivalent.” The intended use must be the same across all predicate devices.

Tip 2: Use pre-submission meeting

In case of uncertainty, we recommend talking to the FDA in advance. The pre-submission meeting is an ideal opportunity for this. You can present your predicate device strategy and obtain feedback from the FDA before submission. In this way, you avoid unnecessary delays and major uncertainties in the clearance process.

Tip 3: Don’t rely on a 510(k) summary

Depending on the submission and manufacturer, the 510(k) summary of a possible predicate device sometimes contains more and sometimes less detailed information. Sometimes, for example, there is a detailed comparison table between the new device and the predicate device, and sometimes only general information on equivalence is provided.

The latter can make comparison difficult and put the 510(k) procedure at risk. In that case, try to obtain the necessary information through other means, such as instructions for use, a service manual, or the company website. Sometimes, it may be necessary to perform comparative tests with the predicate device and generate the necessary comparison data yourself.

Tip 4: Do not omit anything

Do not omit material facts, such as critical differences. If the FDA finds out later, it can lead to serious trouble. If you do not have sufficient information on the predicate device e.g., for certain performance parameters and do not see a way to generate it, state so in the submission file.

The FDA has access to the complete 510(k) file of the predicate device and can access the relevant information if needed (although this is not the optimal way).

Tip 5: Submit clinical data in special cases

Usually, you do not need clinical data for a successful 510(k) clearance. However, there are cases where clinical data is necessary.

There are differences in the indications

For example, suppose the predicate device is to be used for an additional patient population with higher risks (e.g., children). In that case, clinical data may be needed to demonstrate equivalence and, thus, the same level of safety and effectiveness.

For the software to assess anomalies based on image data, this means that since a different anatomical region is addressed in the new device, clinical data (image data) is likely to be needed in this case to demonstrate effectiveness, i.e., successful assessment by the AI algorithm, thus enabling demonstration of equivalence.

There are differences in technology

Different materials, especially for invasive devices, may require the collection of clinical data to demonstrate safety.

An implantable device, as a predicate device made of non-absorbable material, in a new device made of material that the body will absorb over time: In this case, clinical studies may be necessary to demonstrate the safety of the patient.

Equivalence cannot be demonstrated by non-clinical tests alone

There is the case that no model is available for non-clinical bench testing or animal testing.

A phantom that is not available for a simulation of a particular organ for a particular image modality. In this case, real clinical image data should be used.

There are newly emerged or higher risks of the predicate device

If there is evidence of hazards not initially considered or risks incorrectly assessed for the predicate device, this may necessitate the generation of clinical data, even if the predicate device was cleared without such data.

A product type for which serious safety issues were increasingly reported in the post-market phase: In this case, the FDA ordered PMS studies on the already cleared devices and requires the appropriate clinical evidence for 510(k) submission.

6. Summary and conclusion

The selection of a suitable predicate device is often challenging but determines the success of a 510(k) clearance. The FDA is modernizing this procedure and as a first step imposing stricter requirements on the selection of a predicate device. This complicates the most widely used “approval” pathway in the US.

We are happy to help you select suitable predicate devices and determine whether a 510(k) procedure is promising or not. We develop and document the substantial equivalence comparison. In case of uncertainty, we organize and accompany you to an FDA pre-submission meeting.