The EU Data Act came into force in December 2023. It aims to create a new legal framework for handling data that will not only affect US tech giants. The EU Data Act will have an impact on many companies that process data, including medical device manufacturers.

This article will help you assess:

- whether and under what circumstances this proposed law will affect you

- its potential consequences for you, your devices, and your services

The EU Data Act came into force in December 2023, is published on the EU website, and will be binding from September 2025.

1. EU Data Act: what it’s about

a) Situation

There’s no turning back the tide of digitalization:

- A vast number of our activities depend on, are affected by or are even controlled by IT systems.

- These systems’ users are directly and indirectly generating data in unprecedented quantities.

- The US tech companies dominate data storage and processing, and use this data for themselves, e.g., to improve their products and services or for advertising.

- Providers often store data in data silos that even users only have partial access to. This is particularly the case for data generated based on users’ activities but not directly entered by them.

b) Complication

The US tech companies’ dominance threatens fair competition and European companies are finding it difficult to survive in the face of this challenge.

Users/customers of these dominant providers are left with only two options: take it or leave it. Even switching from one provider to another is difficult due to lock-ins.

Since a lot of the data is difficult to access, it is not as easy as it should be to create new applications that link these data sources and thus unlock the benefits of digitalization.

Even public bodies such as public administrators do not get access to the data, which can make it difficult for them to do their job. We saw the consequences of this during the pandemic. For example, it was and still is very difficult to track hospital bed occupation or the population’s vaccine status in real time.

c) Solution

The European Commission believes that the EU Data Act will eliminate these difficulties and create the legal basis for a fair, efficient and effective use of data and thus for the digital transformation of European economic operators.

2. Requirements of the EU Data Act

The rest of this article refers to the draft version of the Data Act. A revision that takes into account the final legal text is planned for early 2024. A revised mind map is already available.

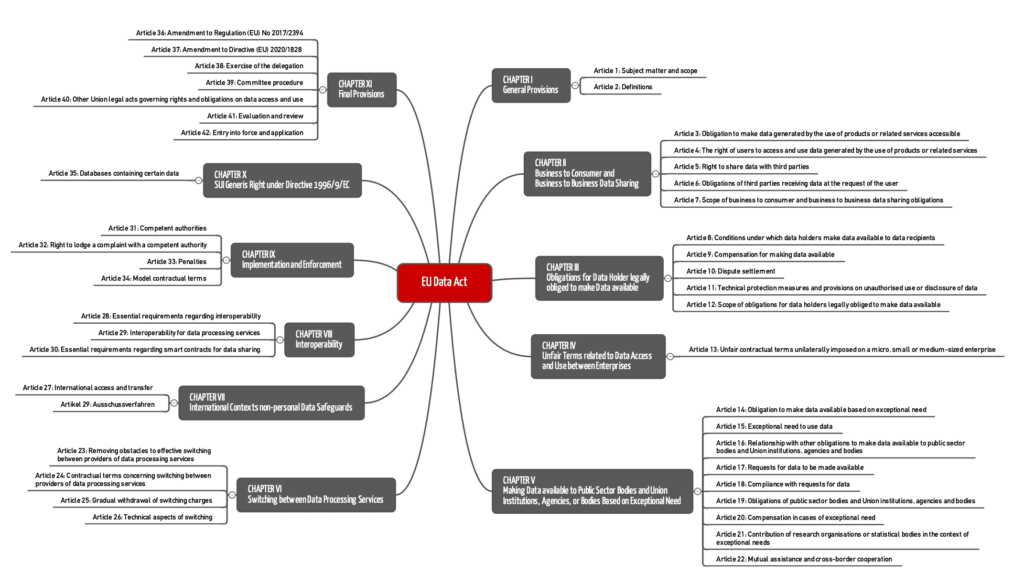

The draft EU Data Act is numbered 2022/0047 (COD). It has a total of eleven chapters.

a) Chapter II: B2B and B2C data sharing

Micro and small enterprises are exempt

A bit of good news first: the requirements of this chapter do not apply to products or related services provided by micro or small enterprises (Article 7).

According to EU Recommendation 2003/361/EC, these are all enterprises that employ fewer than 50 persons and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 10 million.

Companies must make data available

Users must be able to access the data generated by their use of products and services. (Article 4). They can even require the “data holder” (i.e., the party providing the product or service) to make this data available to a third party (Article 5).

This should be done “free of charge” and “without undue delay” or even, where applicable, “in real-time” (Article 4, 5).

For this reason, products must be designed so that these data are, by default, available quickly, easily and securely (Article 3).

Manufacturers are also subject to extensive obligations regarding the provision of information (Article 3). For example, they must provide information on the nature and volume of the data likely to be generated, whether this data is generated continuously and in real-time, and how users can access the data.

b) Chapter III: Additional obligations in the above contexts

The third chapter provides guidance on how to implement the requirements of the second chapter:

- The data must be provided under fair and non-discriminatory terms (Article 8). The data recipient and data sender must sign a corresponding contract.

- Compensation is allowed but must be reasonable. If the data user is an SME, the “data holder” must only charge its costs and not make any profit from the data (Article 9). It even has to disclose its calculations.

c) Chapter IV: Prohibition of unfair contractual terms

The fourth chapter only contains one article. Its aim is to protect SMEs, in particular, from unilateral contractual terms.

In this context, the EU understands unfair to mean, e.g., unilateral contractual terms relating to liability, damages, obligations to provide information, contract termination, etc.

d) Chapter V: Making data available to public stakeholders

If a public authority has an “exceptional need” to access certain data, companies must make the data available to these bodies as well (Articles 14, 15). This would be the case if the data were needed to prevent or respond to a “public emergency.”

The EU has kept another back door open: if the public authority cannot otherwise fulfill its explicitly stated statutory duties, they have a right to access the data.

e) Chapter VI: Switching between data processors

Chapter six changes focus. Now it is no longer a question of who has to provide which data to whom under what circumstances. Now the EU wants to ensure that data users can change their data processor as easily as possible.

To achieve this, the EU regulates, e.g.:

- Notice periods (Article 23, 24)

- The right to move the data to another provider (Articles 23, 24)

- Limits on the cost of this move (Article 25)

- The right of users to “enjoy” (sic!) functional equivalence with the new provider for defined services (“scalable and elastic computing resources limited to infrastructural elements”)

f) Chapter VII: International context

The seventh chapter provides guidelines on how to avoid breaching national or EU laws when exchanging data internationally. This explicitly doesn’t (just) relate to personal data.

For example, the EU requires providers to take specific measures to prevent government agencies from accessing non-personal data if such access would conflict with EU law (Article 27). It’s clear who the authors have in mind.

g) Chapter VIII: Interoperability

“Operators of data spaces”

The requirements established in Chapter 8 governing interoperability are worth noting. They affect “operators of data spaces.” The draft regulation does not define the term “data space.” However, the definition of interoperability seems to suggest it understands it very broadly:

“interoperability” means the ability of two or more data spaces or communication networks, systems, products, applications or components to exchange and use data in order to perform their functions;

EU Data Act, Article 2

The requirements affect data storage providers, such as Amazon Web Services, among others (Article 28).

“Data processing service” providers

In Article 29, the Data Act extends the obligation to data processing service providers. It does define this term:

“data processing service” means a digital service other than an online content service as defined in Article 2(5) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1128, provided to a customer, which enables on-demand administration and broad remote access to a scalable and elastic pool of shareable computing resources of a centralised, distributed or highly distributed nature;

EU Data Act, Article 2

The EU wants to force these providers to be interoperable at all levels of interoperability. It gives itself the option of setting appropriate standards.

Read more about interoperability and the interoperability levels.

“Smart contract” providers

Lastly, the EU also wants to take a hard line with providers whose applications use “smart contracts.” These requirements only partially relate to interoperability, even though Article 30 is also part of Chapter 8 (“Interoperability”).

Instead, the requirements relate to robustness, safe termination of algorithms, archiving, availability, and access control.

The EU regulation remains a little vague, but gives itself the right to have harmonized standards and common specifications developed and then required.

h) Chapter IX: “Enforcement“

The draft EU regulation provides for the same penalties as the GDPR: up to EUR 20 million or up to 4% of annual turnover.

3. Impact on medical device manufacturers

a) Applicability of the EU Data Act

The proposed Data Act covers all products. It explicitly mentions “medical and health devices” in the recitals. It applies to, among others:

- “manufacturers of products and suppliers of related services placed on the market in the Union and the users of such products or services;”

- “data holders that make data available to data recipients in the Union;”

- “providers of data processing services offering such services to customers in the Union.”

This includes medical device manufacturers as well as companies that offer data processing services. The latter would include operators of apps, including digital health applications.

b) Mapping the requirements to medical devices

Data affected

All of the above requirements also apply to medical devices. This includes the requirement in Article 4 mentioned above:

“Where data cannot be directly accessed by the user from the product, the data holder shall make available to the user the data generated by its use of a product or related service without undue delay, free of charge and, where applicable, continuously and in real-time. […]”

EU Data Act, Article 4 (1)

For example, if a user enters their weight into a digital health application, they can access this information directly. This does not create an obligation for the manufacturer.

If, on the other hand, the manufacturer generates further data from the use of its product, it would have to make this data available. This would include data calculated by the manufacturer, such as:

- Static evaluations of vital parameters

- Process indicators, such as process duration or the proportion of process terminations

- User behavior analyses

(Potentially) unaffected data

There will certainly be discussions about what constitutes “data generated by its use of a product.” The following could be controversial or even prohibited:

- Trained machine learning models (probably not because of “trade secrets”)

- Audit logs

- Data whose collection and provision puts patients at risk. For example, providing real-time data on an implant would decrease its battery life and mean explantation is required sooner

Consequences for manufacturers

The requirements of the Data Act have a direct impact on manufacturers and their devices:

- Modify devices

Devices must have interfaces that meet the interoperability requirements and provide the data “where applicable continuously and in real-time.” - Increase IT security

The obligation to make data available to third parties authorized by the user as well significantly increases the IT security requirements. - Manage increased risk of competition

The risk of competitors using the data is increasing. The EU actually explicitly prohibits users (Article 5(5)) from using the data for the development of competing products. But how do you prove something like that? - Bear costs

Providing data “free of charge” (Article 4(1)) increases costs. Article 9 then puts limits on the absence of costs but prohibits profiting from the provision of data to SMEs.

c) Comparable requirements

As tough as many medical device manufacturers will find the requirements, they are not entirely new: other laws have also tried to make accessing data and data portability easier. These laws include the German SGB V Section 374a (data from implants), the GDPR (data portability) and the paragraphs on interoperability in SGB V.

4. Conclusion, summary

a) A powerful intervention

The EU wants to make a big impact with the EU Data Act, and it will affect the future of Europe in the field of digitalization. The consequences and interventions it provides for are correspondingly significant:

- It gives users the right to access the data they provide indirectly as well as directly and to decide what happens to data. “Data holders” even have to provide the data to third parties named by the users.

- That means a substantial restriction in contractual freedom, particularly as the duration of the contract is also limited.

- A lot of manufacturers will have to redesign their devices and IT systems to meet the requirements, including the interoperability requirements.

The EU is targeting US tech giants with the EU Data Act. But it affects a lot of other companies as well since the SME exceptions only relate to a few articles.

b) A lot remains unclear

It is normal for an EU regulation not to answer every question. But in the case of horizontal regulations, the intersection with vertical, i.e., sector-specific, regulations should be better clarified.

It is not even clear that the EU has managed to avoid creating contradictions with already existing regulations. We had a similar conflict with the draft of the aforementioned SGB V Section 374a.

So, we still don’t know:

- Whether medical device manufacturers can get around the requirements by saying that making the data available increases the risks but not the benefits for patients and is, therefore, not allowed under the MDR and/or IVDR.

- What proof a manufacturer has to provide to demonstrate that its trade secrets are at risk.

- Who the Data Act considers to be the user of a device if both physicians and patients use a device and which data then has to be provided to which role.

- Which data manufacturers need to disclose when they train their machine learning models through use.

c) Wait and see can’t be the only strategy

The EU Data Act should be another sign for medical device manufacturers that the era of isolated medical devices is coming to an end.

Digital transformation does not mean equipping the existing metal box (please take this as a metaphor) with a data interface. Digital transformation means thinking in terms of processes.

Devices can be data sinks and data sources. But if they are not able to integrate into higher-level system landscapes and processes, they will find it difficult to survive on the market, whether the EU Data Act comes into effect in its current form or another form.

The Johner Institute supports medical device manufacturers, notified bodies, and authorities in their digital transformation. Get in touch now to work together to find out how you can successfully go down this path.

Change history

- 2024-02-05: Link to final text added

- 2023-11-30: Note added that the Data Act has been passed

- 2022-03-22: First version of the article referring to the draft regulation