Decision Support Systems are also increasingly being used in medicine. If they are medical devices, they must meet the legal requirements (e.g., the general safety and performance requirements).

The hype surrounding Artificial Intelligence, in particular Machine Learning, and users such as Watson are raising hopes for the performance of Decision Support Systems.

This article presents the challenges manufacturers of Decision Support Systems must overcome and gives tips on how these challenges can be mastered. It also explains the corresponding FDA guidance document.

1. Decision Support Systems: Definition and examples

a) Definition

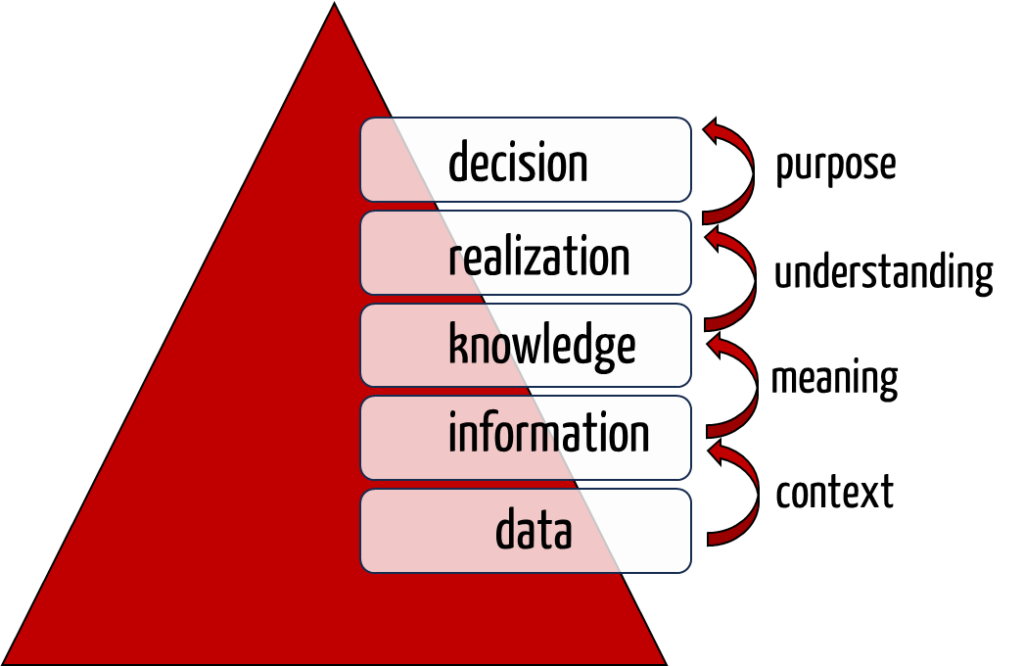

“A Decision Support System (DSS) is a software system that collects, reprocesses, and presents information based on which people can make operational or strategic decisions.”

Source: according to Wikipedia and others

b) Delimitation

Many conventional management information systems and data warehouses cleanse and consolidate data and make it available through dashboards or OLAP cubes. The target group of these systems is usually management.

Decision Support Systems (DSS) follow similar approaches but are usually based on models or advanced mathematical procedures. They claim to present not only information but also knowledge relevant to decision-making. Many DSSs are, therefore, based on data warehouses. They use Artificial Intelligence-based procedures to process the data, especially in the medical field.

c) Examples from the medical sector

Decision Support Systems in medicine, also known as “Clinical Decision Support Systems” CDSS, serve all facets of medical action, such as

- Diagnostic support

- Interpretation of radiological images, particularly for oncological and neurological issues as well as infection diagnostics

- Pathology and histology not limited to an oncological contextDermatology: e.g., assessment of skin lesionsOphthalmology: diagnosis of glaucoma, among other things

- Therapy support

- Drug therapy, e.g., inspection of contraindications and interactions, or the selection of medication, e.g., antibiotics or cytostatic drugs.

- Consideration of therapy alternatives or combinations (e.g., chemotherapy versus radiation versus surgery versus palliative care)Radiation planning

- Triage, decision on priority, and next steps

- Monitoring

- Alarming of intensive care patients, e.g., Patient Data Management Systems (PDMS)

- Monitoring of patients at home

- Differential diagnosis based on findings, the clinic, and other parameters

2. FDA guidance document „Clinical Decision Support Software”

a) Introduction

The FDA published its own guidance document for decision support systems in 2017 as a first draft, followed by a second draft in 2019 and a final version in 2022. On January 6 and 29, 2026, the FDA revised this document once again. The aim of this revision was to largely remove the criterion of “time-critical decision-making,” which would previously have triggered automatic regulation as a medical device.

Anyone hoping to find guidance in the Guidance Document on how to meet the regulatory requirements for this product class will be disappointed. The document merely defines – albeit in great detail – when a CDSS becomes a medical device.

You can download the 2026 version of the “Clinical Decision Support Software” document here.

The FDA bases this on the definition in the legal text, Section 520(o)(1)(E) of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, or FD&C for short. Unfortunately, this text is so poorly written that the FDA now feels compelled to interpret it in the case of DSS.

b) Interpretation of the legal text

According to this, software is only not a medical device if all of the following conditions are met:

- It is NOT used to capture, process, or analyze

- medical images,

- signals originating from an IVD device

- (physiological) signals such as ECGs or EEGs and associated evaluation software.

- It is (only) used to display, analyze, or print medical information about a patient or to display other medical information such as books, clinical publications or guidelines, medication package inserts, or regulatory agency recommendations, even if healthcare professionals use this information to make decisions about preventive measures, diagnoses, and treatments.

- It is used to support healthcare professionals by providing recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of diseases.

This is interesting, as this is precisely what would classify the software as a medical device in Europe. The FDA goes even further and announces that it will not require compliance with regulatory requirements even for software that is not intended for healthcare professionals but for patients.

However, the next paragraph substantially limits this generosity: - The software provides these recommendations in such a transparent manner that users can arrive at these recommendations themselves without having to rely primarily on the software. This presupposes the following:

- The intended purpose of the software (function) is clearly stated.

- The user group is clearly defined (e.g., ultrasound technician, vascular surgeon).

- The inputs on which the recommendations are based are named and also publicly available.

- The logical basis and derivation of the recommendation is made transparent. The FDA also insists that this information is not only publicly available (e.g., in medical literature), but that the intended users also understand this information and can comprehend the recommendation.

In older editions of the document, the FDA attempted to transfer some of these decisions into a table:

| Is the intended user a healthcare professional? | Can the user independently review the basis? | Is it Device CDS? |

| yes | yes | no, it is Non-Device-CDS because it meets all of section 520(o)(1) criteria |

| yes | no | yes, it is Device-CDS |

| no, it is a patient or caregiver | yes | yes, it is Device-CDS |

| no, it is a patient or caregiver | no | yes, it is Device-CDS |

This table is missing in the current edition. However, the FDA continues to distinguish between Device-CDS and Non-Device-CDS.

c) Mapping with the IMDRF document

The FDA felt compelled to align its definition with the IMDRF framework for software as a medical device. You may be familiar with this table:

| state of health care situation or condition | significance of information provided by SaMD to healthcare decision | ||

| treat or diagnose | drive clinical management | inform clinical management | |

| critical | IV | III | II |

| serious | III | II | I |

| non-serious | II | I | I |

The FDA only sees non-CDS in the “inform clinical management” column. The FDA excludes the other two columns:

SaMD functions that drive clinical management are not CDS, as defined in the Cures Act and used in this guidance […]

SaMD functions that treat or diagnose are not CDS, as defined in the Cures Act and used in this guidance […]

Clinical Decision Support Software – Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff

The current edition no longer contains this strong reference to the IMDRF document.

The FDA lists software functions that are considered medical devices because they do not meet at least one of the four criteria for non-device CDS.

| Criterion | Requirement for Non-Device CDS |

| 1 | Not intended for the capture, analysis, or evaluation of medical images or signals |

| 2 | Intended for the display, analysis, or output of medical information |

| 3 | No specific diagnosis or therapy instructions, but recommendations/options |

| 4 | User can independently verify the recommendation (no time-critical decision) |

d) Examples

Decision support systems that are not medical devices

5 Illustrative examples:

| # | Category | Example |

| 1 | Evidence-based prescription sets | Software that displays a list of diagnostic and treatment options to a physician based on clinical guidelines for adult patients with pneumonia symptoms. |

| 2 | Comparison with reference information | Software that compares patient-specific information (diagnosis, allergies, symptoms) with treatment guidelines for common diseases such as influenza, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia. |

| 3 | Interaction warnings | Software that identifies drug interactions and allergy contraindications—e.g., warning that a patient with asthma should not receive non-selective beta blockers. |

| 4 | Preventive care reminders | Software that reminds a physician of preventive measures (e.g., breast cancer screening, vaccinations) based on guidelines and the patient’s medical record. |

| 5 | List of treatment options | Software that recommends considering increased mammography frequency or supplementary breast ultrasound examinations based on diagnosis, family history, and BRCA1 status. |

Common feature

What all these examples have in common is that they provide physicians with information and options that they can review and evaluate independently before making a clinical decision. The software does not make autonomous diagnoses or treatment decisions.

Decision support systems that are medical devices

Category A: Image analysis for treatment planning

| Example | Criteria not met |

| Software creates individual radiation plans from CT/MR images | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software creates 3D models from X-ray/CT data for orthopedic/dental surgery planning. | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software reconstructs CT data in 3D for catheter placement in the bronchial tree | 1, 2, 3 |

Category B: Image analysis for diagnosis

| Example | Criteria not met |

| Software analyzes near-infrared images for diagnosis of cerebral hematoma | 1, 2 |

| Software calculates the fractal dimension of a skin lesion to determine malignancy | 1, 2 |

| Software calculates fractional flow reserve (FFR) from CT images to assess ischemia | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software differentiates between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in images | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software creates prioritized diagnosis list based on image analysis (size, shape, appearance) | 1, 2 |

| CADe/CADx software detects abnormalities and assesses severity in images | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software analyzes digital pathology slides for cell counting and morphology | 1, 2, 3 |

Category C: Signal analysis for diagnosis

| Example | Criteria not met |

| Software analyzes wearable signals (sweat, heart rate, respiration) to detect heart attack/narcolepsy | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Software analyzes cerebrospinal fluid spectroscopy to diagnose meningitis in children. | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software analyzes cough sounds/speech to diagnose bronchitis/sinusitis | 1, 2, 3 |

| Software analyzes breathing patterns to diagnose sleep apnea | 1, 2, 3 |

Category D: Time-critical alarms/diagnoses

| Example | Criteria not met |

| Software analyzes fetal signals to determine the timing of a cesarean section | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Software detects life-threatening conditions (stroke, sepsis) and generates an alarm | 3, 4 |

5 Illustrative examples (selection)

| # | Use case | Why a medical device? |

| 1 | Radiation planning: Software creates an individual treatment plan for radiation therapy based on CT/MR images | Analyzes images (K1 ✗), provides specific therapy instructions (K3 ✗) |

| 2 | Stroke differentiation: Software distinguishes between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in image analysis | Analyzes images (K1 ✗), provides specific diagnosis (K3 ✗) |

| 3 | Skin cancer detection: Software calculates the fractal dimension of a lesion and classifies it as malignant or benign | Analyzes images (K1 ✗), provides specific diagnosis (K3 ✗) |

| 4 | Sepsis/stroke alert: Software analyzes patient data, detects life-threatening conditions, and triggers an alarm | Specific diagnostic output (K3 ✗), time-critical (K4 ✗) |

| 5 | Cesarean section timing: Software analyzes fetal heart rate and uterine contractions to determine the time of surgery | Analyzes signals (K1 ✗), time-critical therapy instruction (K3 ✗, K4 ✗) |

e) Conclusion

Key difference from non-device CDS

| Non-device CDS | Device CDS |

| Displays options and information | Provides specific diagnosis or treatment instructions |

| Physician can independently verify | Physician cannot independently verify (or does not have time to do so) |

| Does not analyze images/signals | Analyzes images, signals, or patterns |

| Example: List of possible medications | Example: “This lesion is malignant” |

The American legislature defines when software is a medical device in such an incomprehensible way that the FDA feels compelled to clarify this in its own guidance document.

Many manufacturers may find it simplifying to be able to market DSS without prior clearance from the FDA. However, this requires, among other things, that the algorithms have been published in scientific literature and proven to be valid.

However, proof of clinical validity is not sufficient to prove patient safety. It is therefore surprising that US legislators (not primarily the FDA) are more generous than European courts in some areas.

3. Regulatory requirements in Europe

a) Basic requirements (MDD, MDR)

Some interpretation guides provide assistance on when software should be classified as a medical device. However, neither the Medical Device Directive MDD nor the Medical Device Regulation MDR set specific requirements for Decision Support Systems. This is understandable because legal texts cannot formulate specific requirements for every product class. The fact that the MDR has done so for mobile platforms is one of the inconsistencies and aberrations of this EU regulation.

Read more about when software is to be classified as a medical device here.

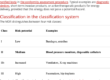

b) Classification according to MDD

Clinical Decision Support Systems are active devices. If they are used for diagnostic support, Rule 10 applies if, for example, they enable direct diagnosis or monitoring of vital bodily functions. These devices then fall into class IIa. Otherwise, Rule 12 applies: “All other active devices are classified as class I.”

The MDD does not say what a “direct diagnosis is” but the MDR does:

“A device is considered to allow direct diagnosis when it provides the diagnosis of the disease or condition in question by itself or when it provides decisive information for the diagnosis.”

Source: MDR

However, Clinical DSS can also be used for therapy. In this case, the classification depends on whether and which therapeutic devices are directly or indirectly influenced.

c) Classification according to MDR

As the name suggests, Decision Support Systems are used for decision support. In other words, they provide information that relates to decisions on diagnoses, therapies, monitoring, or prevention of diseases and injuries.

These devices, therefore, fall into at least class IIa according to Rule 11 of the MDR.

Read more about Rule 11 of the MDR here.

4. Further regulatory requirements

Medical and Clinical Decision Support Systems require medical data, including data that can be directly assigned to patients. Accordingly, this data is particularly worthy of protection. Manufacturers must take data protection requirements into account.

5. Decision Support Systems: Challenges

Manufacturers of Clinical DSS face challenges because not everything that appears technically feasible is technically, regulatory, and ethically possible.

Challenge 1: Intended purpose

Manufacturers must clearly state the purpose and the promised performance (the “claims”). This applies, for example, to the sensitivity and specificity of diagnoses. This concerns the dependence of these claims on boundary conditions such as the patient population (age, gender, co-morbidities, etc.).

It is precisely this clarity that many manufacturers are unable or unwilling to provide.

Challenge 2: Proof of performance, verification

Tests can never prove the correctness of an implementation or device. However, the expected outputs can be specified with classic algorithms such as decision trees.

These outputs are no longer deterministic with many Artificial Intelligence procedures, especially neural networks. This also applies if the database on which the algorithms operate is not constant or the software even expands it independently. The predictability and repeatability of test results are, at the very least, more difficult.

In these cases, manufacturers often fail to define and justify pass-fail criteria.

Challenge 3: Risk management

If the outputs of Decision Support Systems are not deterministic, and in particular, if it cannot be ruled out that they may even make completely wrong recommendations, the risks can hardly be predicted.

The argument put forward by many manufacturers that a doctor would still check the output falls short of the mark. Doctors will hopefully reduce the likelihood that an incorrect recommendation will lead to harm. However, the risk still exists, and proof that doctors actually reduce the probability must be provided.

The benefit argumentation of some manufacturers is also open to attack. This is particularly true when the argument is based on economic savings. A benefit calculation based on the reduction of human error is more helpful. However, this also needs to be proven, e.g., with the help of clinical literature.

Challenge 4: Validation, clinical evaluation

The clinical evaluation must provide evidence that the promised benefit is achieved and that there are no risks that are not already known and assessed as acceptable. This proof of benefit requires a promise of benefit that is often not sufficiently specific (see challenge 1).

The benefit is measured as an improvement over the state of the art. But what is this gold standard? Many manufacturers compare the output of the DSS with the recommendations that doctors would give. But is this really the gold standard? This needs to be justified.

6. Conclusion

Since the 1970s, Clinical Decision Support Systems have experienced many “hypes” with exaggerated expectations, leading to disillusionment. However, with every technical innovation, such as the current “machine learning,” we come closer to the objective of supporting human intelligence with computer systems, sometimes even replacing it.

Advertisements such as IBM’s for Watson raise expectations that can lead to deep disappointment for affected patients. It is up to everyone to decide how responsible such actions are. After all, neither the technological, regulatory, nor medical hurdles have been overcome in such a way that these systems can find their way into mainstream health care.

Change history

- 2026-02-09: Section 2 completely revised due to current FDA Guidance Documents.

- 2022-09-30: Final draft of the FDA guidance document Clinical Decision Support Software added