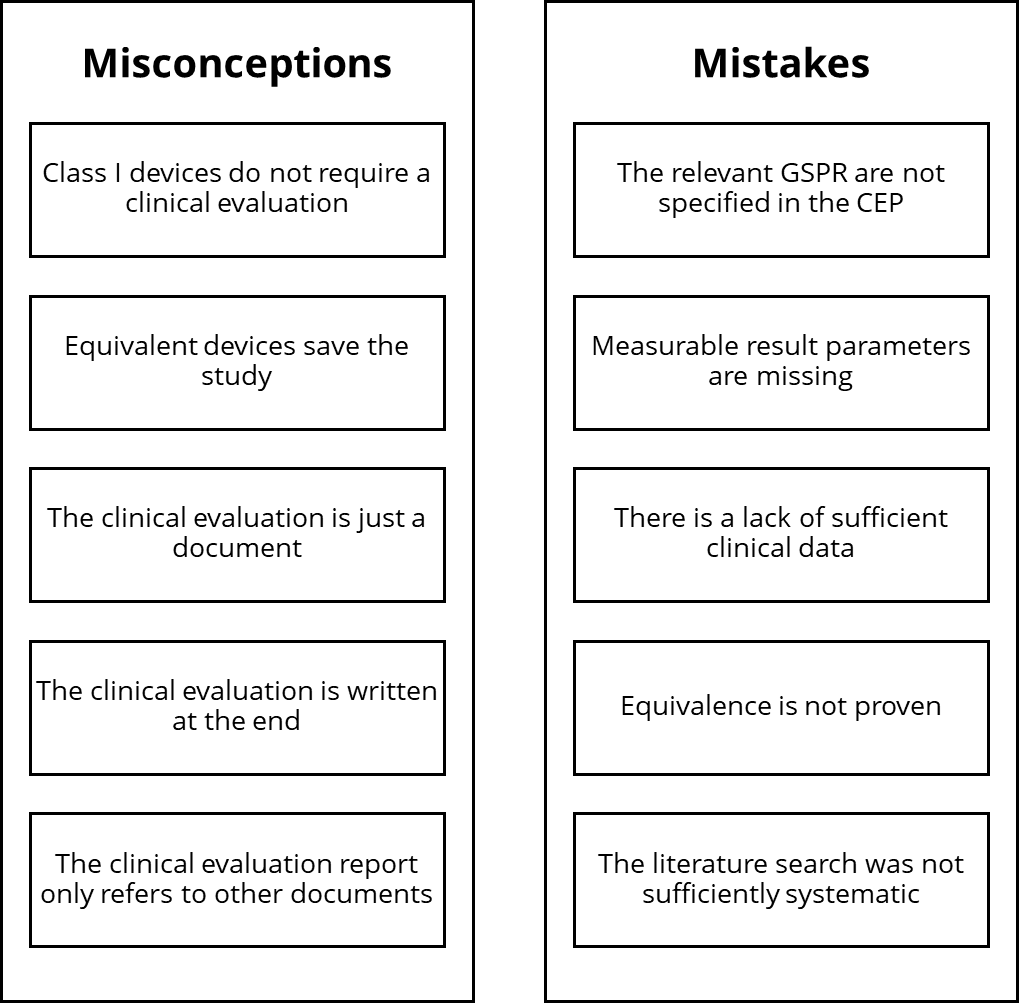

This article outlines the five most common misconceptions and mistakes medical device manufacturers should avoid during clinical evaluation and how to avoid them.

The five most common misconceptions

Misconception 1: A class I device does not require a clinical evaluation

This is wrong.

All medical devices must meet the essential requirements of the MDR (formerly MDD). In this context, both regulations require a clinical evaluation.

Demonstration of conformity with the general safety and performance requirements shall include a clinical evaluation in accordance with Article 61.

MDR Article 5, Section (3)

Neither the MDR nor the MDR permit exceptions, i.e., the waiver of a clinical evaluation.

Although notified bodies are not involved in reviewing the clinical evaluation for class I devices (nor is the other technical documentation), the responsible government authority can request this evaluation at any time.

The MDR and MDD only allow clinical data to be omitted from the clinical evaluation under very specific conditions.

The article on clinical data explains the conditions under which manufacturers can dispense with clinical data. Not on clinical evaluations!

Please also note the overview article on clinical evaluations.

Misconception 2: Equivalent devices save the study (equivalence route)

That is almost correct.

In fact, the MDR allows this so-called “equivalence route.”

A device is only considered equivalent if the manufacturer has demonstrated technical as well as biological and clinical equivalence.

Manufacturers must demonstrate very detailed knowledge of the equivalent products. For class III and implantable devices, contracts are even required below the manufacturer’s level to provide full insight into the technical documentation of the equivalent products.

The requirements for the equivalence criteria are now so high that they can only be met predominantly in the case of in-house predecessor products.

Even a change to the material or a coating regularly leads to a loss of biological equivalence, an extension of the indications leads to a loss of clinical equivalence, etc.

It is also true that manufacturers do not automatically require a study for every new device. Check whether clinical data is even necessary or suitable for your device to demonstrate the general requirements for performance and safety.

Misconception 3: The clinical evaluation is a document

That is wrong.

The clinical evaluation is not a document but a process.

‘clinical evaluation’ means a systematic and planned process to continuously generate, collect, analyse and assess the clinical data pertaining to a device in order to verify the safety and performance, including clinical benefits, of the device when used as intended by the manufacturer;

MDR Article 2, Section 44

However, the output of this process is documents such as

- the clinical evaluation plan,

- a report on the literature search,

- the clinical evaluation report, and

- the plan for the post-market clinical follow-up.

Misconception 4: The clinical evaluation is written at the end

This is wrong.

The clinical evaluation process cannot be started early enough. This is because the clinical evaluation is not only important for planning but also an essential prerequisite for risk management and the definition of risk acceptance criteria, for example. In addition, the clinical evaluation must confirm the assumptions made in the risk management file regarding clinical risks.

However, the final clinical evaluation report is indeed one of the last documents to be completed for the approval of a medical device.

Misconception 5: The clinical evaluation report only refers to other documents

This is wrong.

The clinical evaluation report is not a source document for product information but a summary and assessment.

The clinical evaluation report should be a stand-alone, readable document.

The auditors of notified bodies will be pleased if the clinical evaluation contains all the information in a compact and structured form, saving them from compiling this information from many referenced documents.

However, it is correct that the clinical evaluation documents refer to other documents, e.g., the risk management file, the intended purpose, and the instructions for use.

However, the assessment of the benefit-risk ratio, the quantity and quality of data, and the safety and performance of the device are the subject of the clinical evaluation.

Information such as the intended purpose must have the same wording in all documents. You should always provide a reference to the source document. You will usually summarize the reports from which you take the data to be evaluated and also reference the sources.

The document MDCG 2020-13, the template for the “Clinical Evaluation Report” (CER) that the auditor or reviewer must prepare, outlines what information the notified bodies need to review your clinical evaluation.

The practical MEDDEV checklist from the Johner Institute has proven its worth.

The five most common mistakes

This chapter lists the five most common mistakes and provides tips on how to avoid them.

Mistake no. 1: The relevant GSPR are not specified in the CEP

A frequent criticism from notified bodies is that “the general safety and performance requirements (GSPR) according to MDR Annex I are not specified in the clinical evaluation plan (CEP).“

The non-conformity relates to the MDR requirement in Annex XIV, Part A (1.a).

establish and update a clinical evaluation plan, which shall include at least:

— an identification of the general safety and performance requirements that require support from relevant clinical data;

MDR Annex XIV, Part A (1.a)

Manufacturers often fail to determine and list the GSPR in the CEP.

Article 61 (1) of the MDR requires that at least the GSPR in Sections 1 and 8 of Annex I must be supported by clinical data.

So, list at least these two GSPR in the clinical evaluation plan as requirements that clinical data must support. Also, check your conformity assessment table. The clinical evaluation should appear as a supporting document, at least under performance requirements 1 and 8.

Specifying the general safety and performance requirements (GSPR) 1 and 8 is the minimum requirement that you must fulfill. In addition, you may add any GSPR that you, as a manufacturer, wish to substantiate with clinical data.

Mistake no. 2: Measurable result parameters are missing

Another non-conformity is that “the intended clinical benefit for the patient lacks a clear definition of the (measurable) outcome parameters.“

This non-conformity concerns the MDR’s requirement in Annex XIV Part A, 1a, regarding the content of the CEP.

To plan, continuously conduct and document a clinical evaluation, manufacturers shall:

(a) establish and update a clinical evaluation plan, which shall include at least:

— a detailed description of intended clinical benefits to patients with relevant and specified clinical outcome parameters;

MDR Annex XIV, Part A (1.a)

The clinical evaluation plan should define the specific parameters for the clinical output and the clinical benefit parameters.

A cold pack is intended to reduce pain. The parameter is pain intensity using a VAS score. The manufacturer claims a reduction of 3.5 points after six weeks or 30% after 24 hours.

Read more about this in our article on clinical endpoints.

The MDCG 2020-6 also requires these parameters in chapter 6.1c and refers to MEDDEV 2.7/1 revision 4, Annex A7.2, section C for quantification of the clinical benefit.

Research the specific parameters using data on similar devices, standards, or medical guidelines. Also, the threshold values to be achieved according to the state of the art must be specified.

Mistake no. 3: Lack of sufficient clinical data

Often, a non-conformity is: “Sufficient clinical evidence must be provided to demonstrate the performance and safety of each indication.”

In these cases, the reviewer is not convinced you have sufficient clinical data to prove your claims about the medical device. This refers to insufficient evidence of GSPR 1 and 8 (safety, clinical performance, clinical benefit) based on clinical data.

Article 61 (1) in the second section of the MDR requires manufacturers to specify the scope of the clinical evidence:

The manufacturer shall specify and justify the level of clinical evidence necessary to demonstrate conformity with the relevant general safety and performance requirements. That level of clinical evidence shall be appropriate in view of the characteristics of the device and its intended purpose.

MDR Article 61 (1), second part

This means that you, as the manufacturer, must determine what clinical evidence is sufficient to demonstrate your device’s safety, performance, and clinical benefit. Of course, this determination must be justified.

Benefit from the MDCG 2020-6 to help you determine the clinical evidence. Annex III contains a table that gives you an overview of which data can have which significance.

You must also consider the state of the art of your device.

- Is your device a well-established technology?

Then, a data set from PMS data and user surveys may be sufficient. - Is your device innovative and has the risk-benefit ratio not yet been described in detail?

Then, a prospective clinical investigation may be necessary. In any case, check which clinical endpoints you have defined and whether you can prove them with corresponding data sets.

Mistake no. 4: Equivalence is not proven

Another “classic” non-conformity is this: “The equivalence between the devices is not comprehensible. The documentation to prove equivalence is not sufficient.”

Such a non-conformity is often due to an inadequate assessment of equivalence between two devices. Annex XIV, Part A (3) of the MDR requires that equivalent devices (similar devices) must be almost identical in their clinical and biological characteristics and comparable in their technical characteristics.

Failure to sufficiently consider the clinical, technical, and biological characteristics may be due to the following reasons:

- You have not considered Annex I of MDCG 2020-5.

- You have not carried out scientifically sound comparisons.

- You do not have enough data on the equivalent device to compare.

Point no. 3 is the most common reason why an equivalence assessment fails. In most cases, there is a lack of data:

- Data on specific performance specifications

- Information on the intended purpose

- Data on the materials and removable substances of the equivalent devices

Our tips for a successful equivalence comparison:

- First, collect all data on the equivalized product.

- Carry out the equivalence comparison in accordance with Annex I of the MDCG 2020-5.

- Identify any existing data gaps.

- If necessary, commission tests to fill the data gaps (tests with the equivalence product, for, e.g., the release behavior of soluble substances according to ISO 10993-18).

- Fill the data gaps.

- Complete the equivalence comparison.

If the above measures cannot be implemented or equivalence is disproved, you can transfer the clinical data on the devices to the state of the art. The device then becomes a “similar device.”

If you lose equivalence to a device, you can no longer use the data on a similar device to prove the safety and performance of your own device. However, the data on similar devices will help you in the chapter on the state of the art,

- confirm the adequacy of risk management,

- describe alternative treatment methods and technologies,

- plan your PMCF activities,

- identify clinical outcome parameters and

- define acceptance criteria and thresholds.

Mistake no. 5: The literature search was not sufficiently systematic

Many manufacturers receive this non-conformity: “It is unclear whether the literature search within the clinical evaluation follows a methodologically sound procedure.“

In this case, the documentation on the literature search may not be complete.

Please note the article on literature search in clinical evaluation: 6 tips to save you time and stress.

You need the literature search within the clinical evaluation for two regulatory contexts: the product search itself and the search for the state of the art. Both searches must be conducted and documented systematically.

The MDR requires:

“A clinical evaluation shall follow a defined and methodologically sound procedure based on […] a critical evaluation of the relevant scientific literature currently available relating to the safety, performance, design characteristics and intended purpose of the device […]“

MDR Article 61 (3)

MEDDEV 2.7/1 revision 4, A5 and the MDCG 2020-13, section D cite the following as sound procedures for literature research and evaluation:

- PICO (patient characteristics, type of intervention, control, and outcome queries)

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions

- PRISMA (The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement

- MOOSE Proposal (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

Within the clinical evaluation, benefit from the methods listed here to build your literature search. Document the specific methods used in your literature search report. This will ensure a comprehensible procedure.

Summary and conclusion

Clinical evaluation is one of the most demanding processes. Therefore, it is not surprising that notified bodies find an exceptionally high number of mistakes.

If you know the typical misconceptions and mistakes, you can avoid them.

Do you have questions about eliminating individual non-conformities specifically? Please e-mail us or request a consultation appointment.

Johner Institute’s clinical experts can help you complete your audits, reviews, and approval procedures quickly and successfully with a professional clinical evaluation.