A Quality Assurance Agreement (QAA) is a contract between companies such as medical device manufacturers and their suppliers (subcontractors).

In these contracts, both parties regulate which obligations the suppliers must fulfill regarding the quality of the devices and services supplied.

Find out in this article what content a Quality Assurance Agreement should contain and when standards such as ISO 9001 and ISO 13485, as well as laws, require a Quality Assurance Agreement (QAA).

This article contains the table of contents of a Quality Assurance Agreement, which you can download free of charge.

1. Examples for QAA

Examples of outsourced processes, services, and devices described by a Quality Assurance Agreement are:

- An engineering company designs components or devices (e.g., designs system architectures)

- An engineering service provider develops software that becomes part of the medical device or is used in producing medical devices

- A test house reviews the software on behalf of the person placing it on the market

- A usability lab performs formative and summative usability evaluations for the medical device manufacturer

- A contract manufacturer produces circuit boards or entire components according to specifications

- A service provider maintains medical devices “in the field”

- A hoster operates the server on which the backend of a mobile medical app runs

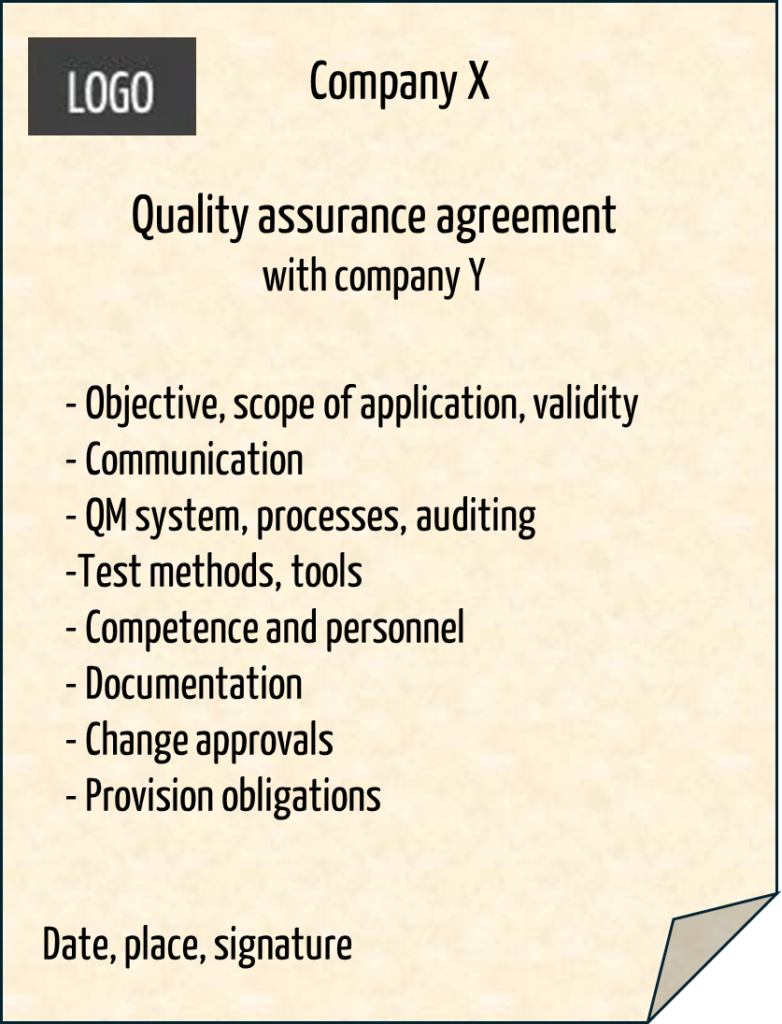

2. Typical contents of a QAA

A QAA should regulate all points required by the standards (see below) that are necessary to avoid risks resulting from defective devices, services, or processes outside the manufacturer.

These points include those listed below.

You can download a table of contents of a Quality Assurance Agreement free of charge here.

a) General

The Quality Assurance Agreement QAA should regulate:

- Objective of the QAA: What does the client want to achieve? This should be formulated as specifically as possible.

- Scope of the QAA: To which devices, services, and processes does the QAA apply?

- Confidentiality: Transparency creates trust and forms the basis for a good relationship between the client and contractor. This is another reason why both parties should be guaranteed confidentiality.

- Period of validity: How long should the QAA be valid for? What are the notice periods?

- Licenses and exploitation rights: The client should be granted the necessary (exclusive and indefinite) use rights, especially for contract developments. These points can be regulated in a separate contract.

b) Communication

The “communication interface” between client and supplier is decisive for the quality of the relationship and, thus, for the success of the QAA. Both parties should, therefore, define the following:

- Communication channels

- Through which media and persons/roles do the two companies exchange information?

- Do they require an confirmation of receipt?

- How are the representations regulated?

- Do these channels differ in “normal cases,” in the event of complaints and escalation? If so, how?

- Response times

- How quickly must the other party respond to incoming information?

- At what times do you guarantee availability? (Office hours, weekends, vacation time)

c) Requirements for the supplier’s organization and processes

Regardless of specific devices or services, many contractors determine requirements such as the following in a Quality Assurance Agreement:

- A QAA may include the obligation to maintain a certified QM system (e.g., compliant with ISO 13485:2016).

- Depending on the nature of the delivery item, the client insists on compliance with specific processes in the QAA and obliges the contractor (supplier) to approve any changes to them.

- Conformity with these processes can usually only be proven through documentation. Therefore, this documentation’s type and scope are usually the subject of a Quality Assurance Agreement. A QAA should also regulate the retention periods of these documents.

- In a QAA, the client can also be granted the right to carry out announced and unannounced audits, inspect agreed locations, processes, and documents, and question the supplier’s employees.

For critical outsourced processes, it is essential to also grant authorities and notified bodies the right to carry out announced and unannounced audits there. - Suppliers also have suppliers. The QAA should therefore specify whether critical processes may be subcontracted. If the QAA already specifies the subcontractors, the contractor could insist on a change approval.

- A QAA may also restrict or require approval for a change of location, e.g., of production or service provision.

d) Requirements for the supplier’s resources, methods, and infrastructure

A QAA can further determine:

- Requirements regarding the availability and competence of employees: Many companies have had the painful experience of having experienced experts present during negotiations who were no longer available after the contract was signed and were replaced by inexperienced colleagues. For this reason, some QAAs determine the involvement of specific persons. The supplier must undertake to communicate or even approve the replacement of these persons.

- Large companies tend to poach the good employees of smaller suppliers. The QAA can include a ban on poaching.

- If raw materials, auxiliary materials, or operating materials can have a negative effect on the delivery item, the QAA should specify these materials and insist on a change approval.

- The same applies to tools and methods, e.g., during development, production, or inspection. For example, in the case of software development, the client could insist that the software be tested using specific test methods, such as equivalence classes and a degree of coverage of at least 80 percent. Or they could require the inspection of biocompatibility in accordance with ISO 10993-1. Other acceptance criteria often include dimensions with limit values and tolerances.

e) Obligations of the client

A Quality Assurance Agreement should not be a unilateral agreement. The client also owes the contractor, for example:

- Documentation that the client must provide: This ranges from requirements for processes and methods to requirements or specifications for devices and acceptance criteria.

- Test obligation: The client is obliged to inspect the goods received within a certain period. If this is not regulated by the QAA, national law (in Germany, e.g., § 377 HGB) applies.

- Duty to provide materials: Clients also regularly provide tools or materials. The quality and period in which this takes place can be the subject of a QAA.

f) Dealing with problems

A QAA helps avoid problems but will not eliminate them. A Quality Assurance Agreement should, therefore, also regulate the handling of problem cases:

- Consequences of breaches of contract: Penalties, procedure, rectification, compensation

- Obligation to take out insurance (the MDR requires this of manufacturers, for example)

- Dealing with problems that the supplier discovers himself:

- Informing the manufacturer (see communication above)

- Root cause analysis, e.g., in the form of an 8D report

- Elimination of causes (incl. deadlines)

These specifications are also important because the manufacturer must comply with its legal reporting obligations, e.g., in accordance with the MPSV.

g) Summary

The above points give you an indication of what your QAA may contain.

It is not a question of addressing all these aspects in a Quality Assurance Agreement. Focus on the points that can impact the conformity of your devices and services. Take a risk-based approach in accordance with ISO 13485:2016 Chapter 4.1.5. In other words, prioritize the requirements in the QAA according to risk.

3. Regulatory requirements for the QAA

a) Requirements of ISO 13485:2016

Chapter 7.4 of ISO 13485:2016 describes the requirements for

- the purchasing process,

- the information that must be provided to the supplier,

- the selection of suppliers and the suppliers themselves,

- the communication between the supplier and the organization, and

- the check of the supplier and the devices and services supplied.

ISO 13485 explicitly requires a written agreement which, among other things, stipulates that the supplier must inform the manufacturer of any changes to the device or service before any changes are implemented! ISO 13485, therefore, requires a Quality Assurance Agreement. This is stated verbatim in Chapter 4.1.5:

“When the organization chooses to outsource any process that affects product conformity to requirements […]. The controls shall be proportionate to the risk […]. The controls shall include written quality agreements.”

ISO 13485:2016 Chapter 4.1.5

EK med 3.9 B16 and B17 are very helpful. Section 5 of B16 provides information on what a QAA should contain.

Please note that a Quality Assurance Agreement as the only instrument for controlling suppliers and outsourced processes is usually not enough! Other control elements are, for example,

- supplier audits,

- surveys, and

- incoming goods inspections.

b) Requirements of ISO 9001:2015

Similarly, ISO 9001:2015 formulates the requirements for the “Control of externally provided processes, products, and services ” in Chapter 8.4. It states that externally provided processes must remain under the control of the company’s QM system. It also requires that the organization must communicate its requirements to the supplier, for example, with reference to

- processes, devices, and services to be provided,

- the need for approvals of methods, releases, etc.,

- the competence of the personnel,

- the cooperation, and

- the control/monitoring of the supplier.

A Quality Assurance Agreement is required to coordinate these requirements with the supplier.

c) Requirements of the MDR

The MDR requires all manufacturers to have a quality management system that regulates, among other things, the “selection and control of suppliers and subcontractors.”

According to the MDR, notified bodies must also carry out “announced and, if necessary, unannounced audits of the premises of economic operators, as well as suppliers and/or subcontractors […].”

d) Summary

There must be no “blind spots” in quality management. These would arise if a QM system of either the manufacturer or the supplier did not control outsourced processes. One would also have to speak of a “blind spot” if a supplier provided critical components or entire devices (e.g., produced) without verifiable and checked quality criteria.

This means that all QM-relevant standards and regulations, such as ISO 13485, ISO 9001, and the FDA’s Quality System Regulations (21 CFR part 820) require the control of outsourced processes, services, and devices. Quality Assurance Agreements describe this control.

4. Common mistakes and problems with QAA

a) General

The most common mistake we come across as auditors and consultants is that there is no QAA at all or that an existing QAA is not known or followed.

Conversely, the persons placing on the market “forget” to check compliance with their own QAA.

b) Content of the QAA

If a QAA exists, the most common problem is that the content is not appropriate:

- The QAA is too generic and too unspecific for the device supplied or the service ordered. The QAA was created by the purchasing department and not by the specialist department and applies to many suppliers.

- Quality Assurance Agreements regularly contain excessive or unnecessary requirements. For example, some of our customers (purchasing) require us at the Johner Institute to confirm in writing that we comply with the RoHS directives. This has a certain absurdity.

- In particular, the QAA requirements do not reference risk management. This also means there is no prioritization and no justification for the necessity of these requirements.

- The QAA contains one-sided and excessive requirements with which large companies take advantage of small companies (especially contractors). This is unfair and usually takes its revenge in the long run.

- The contents of the QAA do not cover the regulatory requirements. The above list helps to check the completeness of a QAA.

- The QAA only contains the contractor’s obligations but not the client’s obligations, which were also mentioned above.

c) Specific difficulties with development contracts

Occasionally, manufacturers use Quality Assurance Agreements to formulate their requirements for developing specific devices or components. In doing so, the manufacturers fail to formulate the responsibilities for the individual activities precisely. They hand over to the service providers a crude and incomplete mishmash of intended purpose, project plans and milestones, product specifications, business expectations, and solution descriptions.

d) Lack of fairness

Many manufacturers (clients) and suppliers (contractors) try to assert their interests in the QAA. This is fine as long as the rules are transparent and fair. However, a lack of fairness also arises from the fact that certain things are not regulated in a QAA.

The following list may serve as a suggestion for how to treat each other fairly and what a QAA can regulate in addition to the points mentioned above:

- Do not poach key personnel.

- Do not create unrealistic cost estimates against your better judgment and take advantage of the inexperience of the other party.

- Guarantee the actual and permanent availability of resources and the independence of individuals.

- Allow the client to track and review the development outputs, e.g., through testing and building infrastructure (this comes at a price, of course).

- Do not allow any uncoordinated dependence on external libraries.

- Provide complete specifications with testable requirements. This also includes the requirements for the documentation that the supplier must generate.

- Agree on regular joint reviews and readjustments.

Make sure that you always have a balanced relationship. Do not demand that one side goes into advance performance. Don’t offer to do so either. Share the risks and take advantage of the opportunities together.

5. Conclusion

A Quality Assurance Agreement is a contract between the client and the contractor, the supplier. Such an agreement should be more concrete and specific than is the case with general terms and conditions.

Quality Assurance Agreements are required by regulations and are necessary to manage risks arising from inadequate processes, devices, and services. Clients and suppliers can also benefit from a QAA. The agreements help to

- fulfill regulatory requirements,

- create a common and documented understanding (this avoids later re-carding and disputes due to inexplicitly formulated requirements and misunderstandings),

- find a basis for pricing (suppliers do much more than just offer devices, processes, or services. This transparency of what is provided helps to make providers comparable),

- enable a higher probability of better-quality processes, devices, and services,

- give suppliers a competitive advantage if they meet the requirements of a QAA,

- carry out inspections and acceptances more effectively and efficiently because the inspection criteria are known from the outset,

- speed up processes and procedures (even during a crisis).

Although Quality Assurance Agreements usually contain more requirements for suppliers than for clients, QAAs should be jointly and fairly negotiated contracts. It is, therefore, a matter of a trusting agreement, not a legal cudgel.

Speaking of “legal,” lawyers should be involved in formulating QAAs. However, the content should come from the technical experts. These are in particular

- the process owners of the outsourced processes,

- the product owner, who knows the device,

- the business economists,

- the risk managers, and

- the quality managers.

Read more about supplier evaluation for software.

The Johner Institute will happily help you draw up your Quality Assurance Agreements and review existing agreements. This will ensure that you have all the QAAs required by regulations and have laid the foundation for a lasting and cooperative partnership.

Change history

- 2020-09-16: Section 4.d) on fairness added