A medical device can cause harm to patients, users, or third parties. The manufacturer must identify this harm to determine the device’s risks and control them.

This article provides guidance on how to determine and document harm in accordance with ISO 14971 and how to use the term “harm” correctly.

1. Definition

ISO 14971 defines the term harm.

“injury or damage to the health of people, or damage to property or the environment”.

DIN ISO 14971:2022, Chapter 3.3 with reference to ISO/IEC Guide 63:2019, 3.1

The harms, according to ISO 14971, are usually:

- Impairment of body structure (e.g., cut, burn, broken bone)

- Impairment of body function (e.g., ability to move, ability to see, capability to purify blood)

- The reduction in life expectancy

- Mental impairments

The latter are only included among the types of harm from the third edition of ISO 14971 onwards. Before that, harm was limited to physical injuries and damage.

According to ISO 14971, harm also includes harm to property or the environment. They thus include financial harm as well.

It is usually not expedient to assess the harm to goods and the environment with the same risk acceptance matrix as the harm to health. This would presuppose that the severity of this harm is comparable. For example, the manufacturer would have to equate a life-threatening harm with a sum of money.

2. Typical mistakes in determining the harm

Mistake 1: Assuming there is one (only) harm

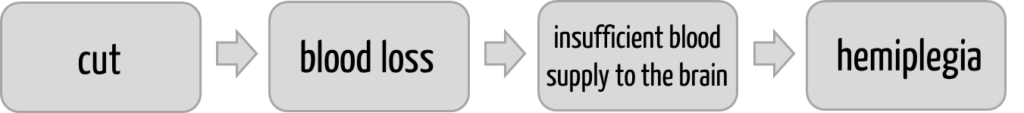

Many manufacturers assume that they must enter one harm in the corresponding column in the “risk table.” This is usually not the case. There is not only one harm but an entire chain of harm in which each individual element is a harm in the sense of the definition (see Fig. 1).

Each element of this chain of causes meets the definition of ISO 14971 because each element represents a physical injury or damage to health.

Each element of this chain of harm will occur with a different probability and thus represent a different risk in the sense of ISO 14971.

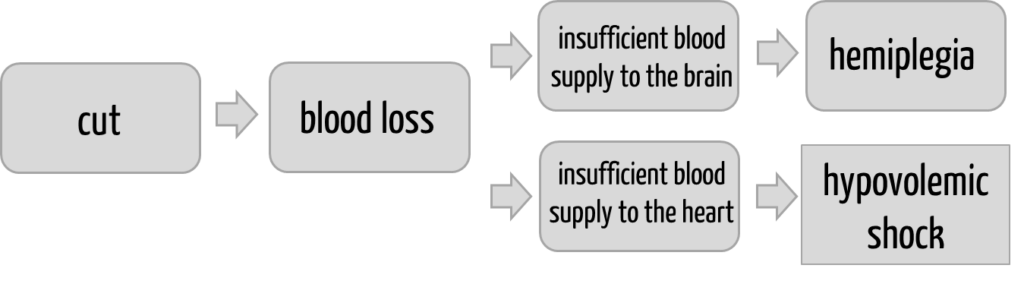

Mistake 2: Assuming the “linearity” of the chain of harm

These chains of causes are usually complex and not linear, as Fig. 1 suggests. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 below:

If you want to carry out a risk analysis and specifically investigate this last part of the chain of causes, you will need

- a physician and

- a risk manager who documents the output of this physician in the risk management file consistently and in accordance with the requirements of ISO 14971.

Mistake 3: Stating harms that are not harms

The following entries are regularly found in the “harm” column of the risk table:

- defective product

- serious adverse event

- harm to patients

- expensive rectification

Do you recognize the problems? You will find a resolution at the end of the article.

Mistake 4: Overlooking harm

Identifying the harm is one task of hazard and risk analysis. This analysis must be methodical.

Read more about risk analysis and the used methods, such as FMEA, PHA, and FTA.

The harm that is often “overlooked” can arise from

- application errors

- foreseeable misuse

- other normal use (e.g., storage, transport, cleaning)

- production

- failure to achieve the intended purpose (e.g., delayed or incorrect display of laboratory values in an IVD or insufficient removal of substances requiring dialysis from the blood in a dialysis machine).

Please let us know if you would like assistance in determining the harm. Feel free to contact us using our contact form.

Mistake 5: Wrong assessment of the harms

To determine the risks, manufacturers must estimate the probability and severity of the harm occurring.

Read here how to precisely quantify and determine the severity of harm.

3. Conclusion

If you want a solid basis for a robust and ISO 14971-compliant risk management file, you must also use the term “harm” precisely. This requires knowing and avoiding the above mistakes. Competent risk management teams are best at this.

The Johner Institute’s risk management seminars and the Medical Device University help to ensure this competence.

Change history:

- 2024-10-01: Article completely rewritten. Content from the article on the severity of harm is also included.

- 2014-03-14: First version of the article published

Resolution:

| Entry in the column “harm” | Comment |

| Defective product | A defective product would theoretically be a case of property damage and, thus, harm as defined in ISO 14971. However, the description of “defective product” would first have to be described in more detail, and then it would have to be decided under which category it falls. Examples: – “Defective product” in the sense of malfunction or complete product failure (lack of availability of the product for urgent diagnostic or therapeutic use) – here, the defective product would be no harm but a hazard that can then lead to harm to the patient (e.g., hypoxia or death in the event of a defective respirator in operation) – “Defective product” in the sense of a sharp-edged housing due to a material fracture – here, the defective product would also be no harm but a hazard. The possible harm to the user, patient, or third party would be, for example, a cut – “Defective product” in the sense of economic damage to the product itself is not considered by risk management according to ISO 14971. |

| Serious adverse event | This harm is too unspecific. The “serious” corresponds to a severity. This is to be documented in another column. |

| Harm to patients | This harm is described in a way that is too unspecific. It is not enough to state who the harm affects. |

| Expensive rectification | See comment on “defective product.” It is ethically difficult to equate economic and health-related harm. Therefore, evaluating these “types of harm” in different risk acceptance matrices is better. |