IEC 62366-1 uses the concept of (hazard-related) use scenario.

The FDA uses the concept of critical (user) tasks. In development, one works with use cases and user stories.

This diversity of terms makes a common understanding difficult. However, this is necessary to create consistent and legally compliant usability files and to avoid regulatory problems. This article provides clarity.

1. Why you should deal with use scenarios and user tasks

a) Because it is required by law

Manufacturers must demonstrate the usability of their medical devices and their safe use. The FDA and laws in Europe and other markets require this.

Manufacturers should describe the use scenarios and user tasks for both the US and EU markets. Neither use cases nor user stories are required.

Overview

| regulations / concept to be described | FDA | MDR/IVDR | IEC 62366-1 |

| Use Scenario | yes | no | yes |

| Hazard-Related Use Scenario | no [1] | no | yes |

| User Task | yes | no | yes |

| Critical Task | yes | no | no |

| Use Case | no | no | no |

| User Story | no | no | no |

FDA requirements

In its guidance document Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Marketing Submissions, the FDA requires manufacturers to identify critical tasks and eliminate or at least reduce use-related hazards. The same requirement is found in the FDA’s HFE Guidance.

In the same document, the FDA also requires to describe use scenarios:

“The submitter should also describe each use scenario included in the human factors validation testing and list the critical and non-critical tasks that constitute each use scenario.”

FDA Draft Guidance: Content of Human Factors Information

in Medical Device Marketing Submissions

MDR and IVDR requirements

The EU MDR and IVDR regulations only require the risks arising from use errors to be eliminated or minimized. The terms “use scenario” and “critical task” are not used in the regulations.

IEC 62366-1 requirements

As with all general safety and performance requirements, manufacturers should use harmonized standards to demonstrate compliance with these requirements.

Regarding usability, EN IEC 62366-1 is the standard to be harmonized. It requires manufacturers to

- identify and describe the hazard-related use scenarios (his assumes that manufacturers have identified and described the use scenarios as a whole),

- describe the tasks and their sequence,

- select the hazard-related use scenarios that are to be part of the summative evaluation (usually usability tests),

- justify this selection,

- specify the UI based on the use scenarios, and

- plan and conduct the summative evaluation for each selected hazard-related use scenario.

b) Because this allows to develop better devices

Products are usable if they fulfill the tasks of the users as effectively, efficiently, and to their satisfaction as possible. In fact, this is the definition of usability (according to DIN EN ISO 9241-11:2018-11).

To do so, it is necessary to identify the tasks and consider how and in what order the users should interact with the device. These are the use scenarios (as expressed by the definition).

The legal requirements for medical devices are limited to errors of use that could affect the safety of patients, users, and third parties. Satisfaction of users is not required.

2. Definitions and delimitations

a) Use scenario and hazard-related use scenario

IEC 62366-1 defines the term “use scenario”:

“specific sequence of tasks performed by a specific user in a specific use environment and any resulting response of the medical device”

DIN EN 62366-1:2021-08, Chapter 3.22

The subset of hazard-related use scenarios is particularly relevant:

“use scenario that can lead to a hazardous situation or harm”

DIN EN 62366-1:2021-08, Chapter 3.8

The standard notes that hazard-related use scenarios are often associated with a use error. In fact, in practice, this should almost always be the case.

b) (User) tasks und critical task

Although IEC 62366-1 speaks of tasks, it does not recognize any concept of “critical tasks” in the normative part. In the informative part, it writes:

“A TASK in a HAZARD-RELATED USE SCENARIO in which a USE ERROR can lead to significant HARM, can be thought of as a “critical task.”

In contrast, FDA knows and defines the term “critical task”:

“A user task which, if performed incorrectly or not performed at all, would or could cause serious harm to the patient or user, where harm is defined to include compromised medical care”

FDA guidance documents

In the same document, it also defines the terms “task” and “serious harm”:

task

“One or more user interactions with a medical device to achieve a desired result“

serious harm

“Includes both serious injury and death”

FDA Draft Guidance: Content of Human Factors Information

in Medical Device Marketing Submissions

In defining the term “harm,” the FDA falls back on the definition in IEC 62366-1.

The definition of “serious injury” can be found elsewhere:

“An injury or illness that is life-threatening, results in permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure, or necessitates medical or surgical intervention to preclude permanent impairment of a body function or permanent damage to a body structure. Permanent means irreversible impairment or damage to a body structure or function, excluding trivial impairment or damage.”

FDA Draft Guidance: Content of Human Factors Information

in Medical Device Marketing Submissions

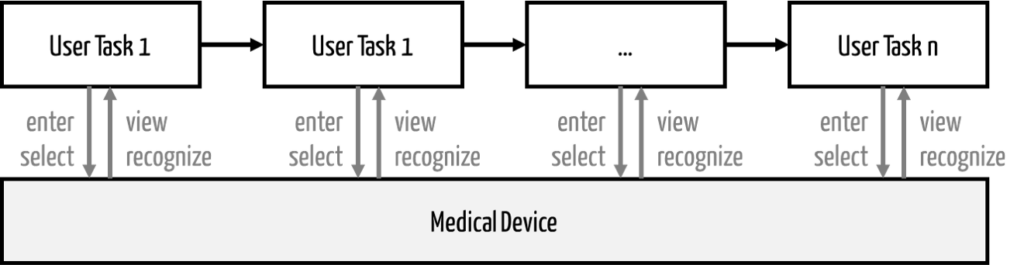

c) Delimitation of use scenario and user task

A use scenario consists of a sequence of user tasks on a system (device) (see Fig. 1).

If a user task is “critical,” i.e., there is a “critical task,” the use scenario containing this task must also be evaluated as “hazard-related.”

d) Delimitation of use scenario and use case

Definition of „use case“

Unfortunately, there is no uniform and authoritative definition of the term “use case”: For example, the following can be found:

- “A use case describes a sequence of actions a system performs that yields an observable result of value to a particular actor.” [Ivar Jacobson]

- “A use case is a sequence of actions or steps that typically define the interaction between a role (also called an actor in UML) and a system to achieve an objective.” [Source]

- “A use case specifies a sequence of actions that the system performs in interaction with the environment.”

Comparison of the definitions with use scenarios

These definitions are not congruent.

- According to Ivar Jacobson, it is only about the system. It is NOT about the actions of a user.

- The second definition talks about “actors.” Examples of these actors are not only users but also other systems.

- The third definition does speak of a sequence of actions. However, these are actions that the system performs with the environment, not actions that a user performs with the system.

This makes it clear that use cases (according to Ivar Jacobson’s definition) and use scenarios have nothing to do with each other directly:

| Use Scenarios | Use Cases |

|---|---|

| Use scenarios are used to specify the sequence of user actions and system reactions at the usage level in such a way that the user requirements are met. | Use cases translate the use scenarios into scenarios that now specify the performance of the system. From the point of view of usability, this already takes us to the solution level: What does the system have to do in order to fulfill the user requirements? |

This is exactly what makes use cases valuable: they allow you to translate the use scenarios into system performance without trying too hard, quite naturally! One consistently uses use cases after having specified user requirements and scenarios beforehand.

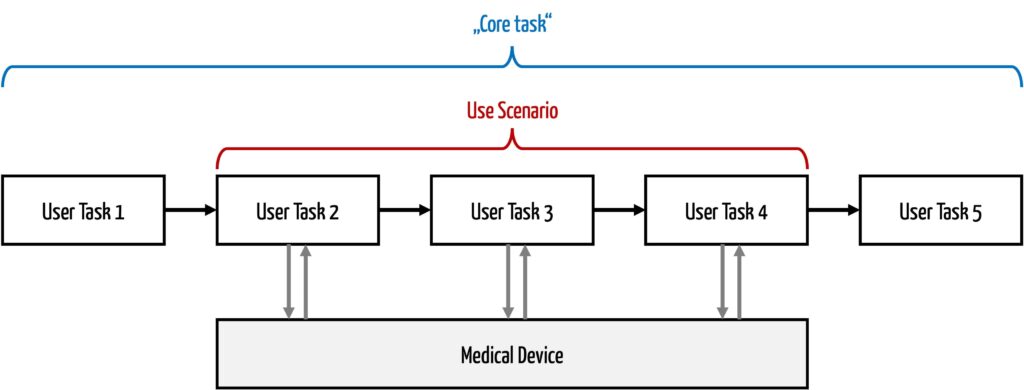

e) Delimitation of use scenario and core task

A use scenario does not correspond to a core task. A core task is a task that a person must perform in order to achieve an objective (typically in terms of intended use).

A core task does not have to relate specifically to the use of a device. For example, a core task could be “taking a pulse,” which could be done without a device. A use scenario, on the other hand, includes the technical solution, so it would describe the use of a heart rate monitor from the user’s perspective. A core task usually consists of several subtasks. Systems support some of these subtasks, sometimes all of them. The subtasks that users perform on the system form the use scenario.

f) Delimitation of use scenario and workflow

The term workflow has multiple meanings, which leads to difficulties not only in usability engineering.

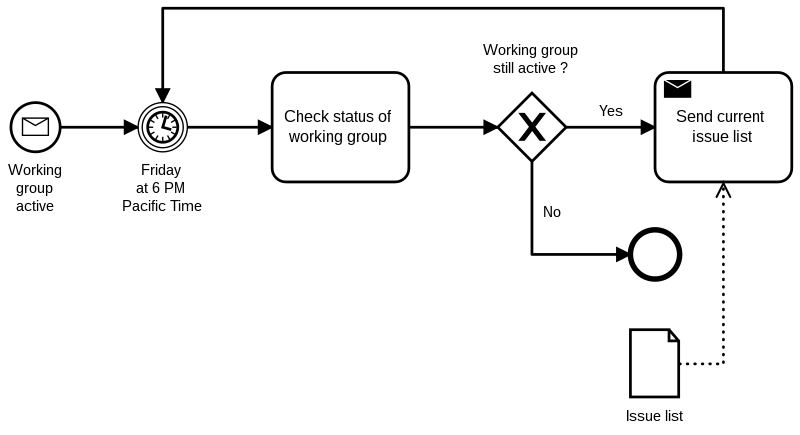

Workflows and processes

On the one hand, there are workflows in the sense of processes. They define how people work together across roles and organizational units.

For example, these workflows can be modeled and described using Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN).

Workflow in usability engineering: use scenarios and tasks

On the other hand, the term “workflow” is used as a synonym of “use scenario.” Then a workflow describes how (individual) people interact with systems in the context of a task.

g) Delimitation of use scenario and user story

Objective and formulation templates

Many manufacturers use user stories to formulate requirements – usually for software – in the language of the customer or user. To do this, they use “natural” formulations that correspond to everyday language but usually resort to sentence templates such as “As a <role> I can <activity> so that <business value>.”

An example of a user story is:

“As an EPAT (Extracorporeal Pulse Activation Technology) technician I can adjust the energy delivered in increments so as to deliver higher or lower energy pulses to the patient’s treatment area.“

Comparison with use scenarios

User stories do not determine sequences of activities. They are, therefore, not a substitute for use scenarios.

User stories from a regulatory perspective

There are no regulatory requirements that oblige or even suggest manufacturers to use user stories.

The Johner Institute even explicitly advises against it because user stories often lead to manufacturers not meeting regulatory requirements precisely. More on this in chapter 4 b).

3. How to document use scenarios and user tasks

a) What the regulatory documents say

Neither the FDA nor IEC 62366-1 set specific requirements for how manufacturers should document use scenarios and tasks. IEC 62366-2 only says that there are many possibilities:

USE SCENARIOS can be written in many different forms, ranging from story-like narratives to simple lists of USER TASKS or steps in a TASK.

IEC 62366-2:2016, Chapter 11.1

A task list is often not sufficient to meet the requirement of IEC 62366-1 to describe the use scenarios. For example, the outputs to be achieved or postconditions that can be used to review whether the user has successfully completed the task are missing.

b) What the Johner Institute recommends

This is another reason why we recommend describing each use scenario as follows:

Part 1: Cross-task aspects

First, there is a description of the following aspects:

- Intended user groups

This can be a reference to the roles specified in the intended use or “use specification.” - Intended use environment

Again, such a reference is recommended if the (extended) intended use describes this information with sufficient granularity. - Preconditions

This section should describe preconditions that must be met in the system or use environment, e.g.,- in the system: permissions have been granted, and data has been captured.

- in the use environment: information or additional tools are available.

- Postconditions

The type of postconditions is similar to the preconditions. An example of a postcondition is that certain information must be recorded in the system.

Part 2: Tabular description of the tasks

Then follows a table, which specifies the tasks with their attributes line by line:

| task, e.g., action of the user | reaction of the system (via UI) | possible use errors | possible root cause | hazardous situation | possible harm with level of severity | critical task (y/n) | risk control measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| enter new drug for selected patient | show new drug for the patient | drug entered for wrong patient | user was distracted or confused because of patients with similar names | patient takes wrong medication | serious | yes | plausibility inspection (medication and diagnoses); display of the patient photo |

4. Practical tips: What you should consider

a) Choose the right granularity for use scenarios

Manufacturers should choose the right granularity when describing the use scenarios:

- Too high a granularity means unnecessary effort and leads to the use scenario changing even for the smallest changes. This increases the effort for “re-validation.”

- Too low a granularity may not allow individual critical tasks to be identified, leading to the risk that these tasks have not been summatively selected and evaluated. As a result, potential use errors in their identification may be overlooked, and an unsafe device may be placed on the market.

Therefore, especially for software UIs, the following heuristics can help:

- A core task consists of seven +/- two subtasks, and core tasks should not be confused with use scenarios (see above).

- Individual mouse clicks do not represent a task.

- For screen-based devices, a screen often represents a subtask or task within the use scenario.

b) Be careful with user stories

User stories blend the various concepts that medical device manufacturers must describe:

| section of the formulation template | content | suitable documents |

|---|---|---|

| As a <role>… | characterization of the users | intended use or/and use specification |

| …I can <activity>… | description of what the user must be able to do on the system | user requirement (if it is already described how the user can do it, it is even the system specification) |

| … so that <business value>. | purpose of this action | intended use |

The regulations require “traceability” between intended use, stakeholder requirements, and system requirements or system specifications. This will not succeed if they are all mixed up in one sentence.

Working with user stories is no substitute for requirements engineering, especially for systematically deriving user requirements.

Therefore, do not use user stories. They cause more harm than benefit.

c) Use professional requirements engineering

Instead, proceed as follows:

- Formulate the intended use, and thus the medical purpose and specified users.

- Derive the requirements, the user requirements, and the core tasks using the context method.

- Based on this, specify the use scenarios and based on these, the interactive device.

- Validate this specification.

5. Summary and conclusion

a) Variety of terms

There is a large number of terms that sound similar but should not be confused with each other:

- use scenario and hazard-related use scenario

- user tasks and critical tasks

- core task

- use case

- user story

Manufacturers must not confuse these terms. Otherwise, there is a risk of regulatory difficulties.

b) View through the regulatory lens

From a regulatory point of view, only the first two points are relevant. Even if the FDA places somewhat more emphasis on the concept of tasks or “critical tasks” and IEC 62366-1 places more emphasis on the concept of “use scenarios,” it is essential in any case to identify use scenarios and their tasks in as much detail as possible and to describe potential hazards and the severity of any harm in great detail.

c) Procedure

The description of use scenarios does not replace requirements engineering, nor does it constitute the beginning of requirements engineering. Rather, use scenarios represent an intermediate step. This is because use scenarios are already part of the solution domain.

d) Meaning

Precisely identified use scenarios are critical for

- task analysis and risk analysis,

- safe medical devices,

- the summative evaluation of medical devices,

- a compliant usability file and hassle-free approvals,

- medical devices fit for use and sought after by customers.

Therefore, manufacturers are well positioned if they systematically identify and describe the use scenarios and evaluate them during usability tests.

The Johner Institute supports medical device manufacturers in

- identifying and describing use scenarios,

- selecting safety-related use scenarios, and

- formative and summative evaluations in the institute’s own usability labs (in Germany and the USA).

With this help, you will meet all the relevant usability requirements of the FDA, EU, and other markets.

If you want to learn more, feel free to get in touch, e.g., via the contact form.