When selecting an operating system, do medical device manufacturers have to ensure that the operating system is IEC 62304-compliant? What does the FDA say? This article…

- lists the regulatory requirements (e.g., IEC 62304, FDA) for operating systems

- provides tips for selecting operating systems

- examines whether there can or must be an IEC 62304 certification for operating systems.

1. Regulatory requirements for operating systems

1.1. General

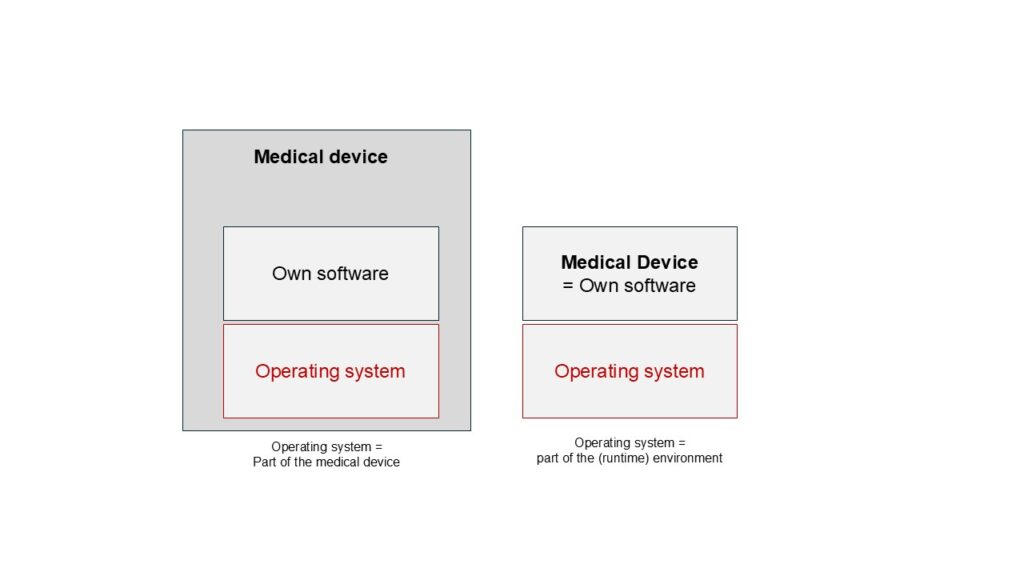

The regulatory requirements for an operating system depend on whether it is part of the product or the runtime environment.

1.2. Regulatory requirements in Europe

1.2.1. The operating system is part of the medical device

In the case of medical devices, all software (including its own software and operating system) is part of the device. Therefore, the complete software must be documented in accordance with the standard IEC 62304 (“medical device software—software life cycle processes”).

Here, two cases must be distinguished:

- The medical device manufacturer has developed the operating system itself: In this case, the complete software life cycle for the operating system must be documented. In particular, the manufacturer (depending on the safety class) must document the software requirements, architecture (including detailed design), software tests, and software approval and follow a development process.

- The medical device manufacturer uses a (commercially) available operating system (e.g., Windows, Linux): In this case, the manufacturer must treat the operating system as a SOUP and describe, for example, the requirements for the SOUP and the conditions for its use.

IEC 62304 would even allow a self-developed operating system to be declared as a SOUP, thus avoiding the documentation of the software architecture and software tests. However, this is not recommended.

The Medical Device University explains how to document your software, including your SOUPs, in accordance with IEC 62304.

1.2.2. The operating system is NOT part of the medical device.

For standalone software, the manufacturer requires hardware (e.g., PC) and an operating system runtime environment. The operating system is then not part of the medical device, i.e., there is no requirement that it has been developed in accordance with IEC 62304.

However, the manufacturer must specify and communicate these requirements to the operators/users. The choice of operating system directly affects the software requirements specification (according to IEC 62304, Chapter 5).

1.2.3. Risk management for operating systems

In both cases, the manufacturer must analyze and control risks associated with the operating system. For example, the manufacturer should investigate what happens if, for example,

- the operating system is defective,

- the intended operating system is not installed,

- the operating system has not been updated,

- Software installed in parallel (e.g., firewall, antivirus software) can interfere with the operating system’s normal function (e.g., access to resources such as the network or memory cannot be provided).

1.3. FDA regulatory requirements

The FDA formulates requirements for operating systems for both the manufacturers and operators of medical devices and healthcare IT.

1.3.1. Requirements for operating systems as OTS

The FDA considers operating systems that are part of a medical device to be off-the-shelf software (OTS). It says that OTS operating systems do not have to be validated as separate programs:

„Off-the-shelf operating systems need not be validated as a separate program. However, system-level validation testing of the application software should address all the operating system services used, including maximum loading conditions, file operations, handling of system error conditions, and memory constraints that may be applicable to the intended use of the application program.“

(Source: Software Validation Guidance)

However, the FDA wants to see the data flow verified for drivers:

„[…] the validation process for the OTS driver software package should be part of the system interface validation process for higher levels of concern. This includes the verification of the data values in both directions for the data signals; various mode settings for the control signals in both directions (if applicable); and the input/output interrupt and timing functions of the driver with the CPU and operating system.“

(Source: OTS Guidance)

In general, manufacturers must comply with the requirements for using off-the-shelf software. For example, they must enclose “special documentation” if the OTS still has a significant level of concern after the risk-minimizing measures. This may involve an audit of the OTS manufacturer. It is rather unlikely that Microsoft (for example) would allow its cards to be so clearly seen.

1.3.2. Cybersecurity requirements

The manufacturer and operator of all software (regardless of whether it is an operating system) must comply with the cybersecurity requirements.

Read an article on the corresponding cybersecurity guidance document here.

The article OTS versus SOUP explains the differences between the two concepts. It points out that the OTS requirements do not apply to components of a medical device.

1.3.3. Other requirements for development

When selecting operating systems, manufacturers should consider the following points:

- The requirements for operating systems that are part of the medical device must be defined.

- The minimum requirements that software (standalone medical device) can assume as a runtime environment must be specified. These include the operating system. These requirements are often expressed in formulations such as: “Prerequisite is Windows XY with Service Patch YZ or higher.”

- The operating system must be included in the Software Requirements Specification (SRS) and the Software Design Specification (detailed software architecture).

- The integration tests must check the interaction of the software with the operating system.

- The system tests must also be carried out on the objective operating system.

1.3.4. Special case: Requirements for process software

The FDA requirements apply to (software) development and production if process software is used. This process software must be validated, even on the actual operating system.

2. Selection criteria for (real-time) operating systems

We have received the following question via our MicroConsulting service: “What should I look out for when negotiating with an RTOS manufacturer?”

2.1. Requirements of some manufacturers

Medical device manufacturers regularly inundate RTOS manufacturers with demands:

- The RTOS must be truly real-time (and then comes an absurd demand in µs).

- The RTOS must require only a minimal amount of memory (then follows an unrealistic demand in kB).

- The RTOS must run on as many processors as possible (including an impressively long list of processors).

- The RTOS must cost as little as possible (preferably nothing).

Such demands may be helpful in price negotiations, but they are less useful for product selection.

2.2. Targeted requirements

Manufacturers have had good experiences with defining what they need:

- How quickly does the system have to react? Do safety-critical functions depend on it? The answer follows from risk management.

- Which interfaces should the system operate? Which ones do you need as a manufacturer?

- Does the system get by with the actual hardware resources that you provide?

- Do you need access to the source code?

- What references are there? How many times has the system already been sold?

- Were there any problems? For example, did you have to report anything to the BfArM?

- Are there any verification documents? Do you need them at all?

- etc., etc.

Remember: the RTOS is a SOUP. IEC 62304 requires that you formulate the SOUP’s requirements and describe the environment in which it may be required.

2.3. Conclusion

Medical device manufacturers should not be making demands of RTOS manufacturers until it is clear what is needed in quantity and quality. Otherwise, asking which is the best RTOS is similar to asking whether Windows or Linux is better – both questions are equally futile.

3. Certification of operating systems according to IEC 62304?

An increasing number of operating system manufacturers claim that their products are IEC 62304-certified. For example, a company’s press release was headlined “<product name> real-time operating system for medical device development is IEC 62304 compliant.”

3.1. Why this certification is not possible/does not make sense

IEC 62304 requires risk management according to ISO 14971. This is impossible for an operating system without knowing the exact product and its intended purpose.

Without this knowledge, safety classification is also difficult. Therefore, everything would have to be classified as class C. This would significantly impact the scope of the requirements specification, the architecture document, the unit/component tests, etc.

The claim that the operating system is “IEC 62304-compliant” must be generally questioned. This is because there are currently no accredited bodies that issue this certificate. Especially since IEC 62304 is a process standard.

3.2. The benefits of having the operating system IEC 62304 certified

The claim that their operating system is certified at least shows an understanding that software quality assurance has a market value. May this be a good example for all medical device manufacturers.

If you were to receive test reports and architecture from the RTOS manufacturer, which I don’t think you would, you could make more accurate statements in risk management. However, these “self-certifications” are usually not helpful for the certification of medical devices:

Ultimately, you have no choice but to trust the manufacturer – or (perhaps more importantly) to let the statistics speak. In this respect, you should trust the frequently used operating systems rather than the supposedly certified ones because the more frequently an operating system is used, the more likely errors will be detected and can be reacted to.

In other words, ultimately, the deciding factor is the probability that an operating system has or does not have errors relevant to one’s own product. It must be proven that these probabilities differ by orders of magnitude between certified and frequently used products.

Conclusion: As long as you don’t have the complete documentation, including the OS code, the RTOS is and remains a SOUP.

4. Updates to operating systems: a dilemma

Some medical devices, such as a heart-lung machine used recently, make you shudder: they run on outdated operating systems that are no longer patched.

4.1. Dilemma for manufacturers?

For manufacturers, updating the operating system for products already on the market involves a great deal of effort:

- Revise software requirements

- Adapt software architecture and SOUP list

- Repeat software tests (in part) with the new operating system

- Define and validate the update process

- Update the SOUP list and SBOM

- Release software again

- Update accompanying information if necessary

- Adapt post-market activities (e.g., include new SOUP in follow-up)

- Carry out the update and check its success

Customers (e.g., hospitals) are rarely willing to pay for all of this.

However, there is no way around it. As part of post-market surveillance, manufacturers must continuously and proactively assess whether the benefit-risk ratio is still given and whether all risks are controlled. This also includes risks arising from unsafe operating systems.

4.2. Dilemma for operators

Operators are just as obliged as manufacturers to ensure IT safety. This requirement can be found, among other places, in the Medical Devices Operator Ordinance.

If an operator realizes that a medical device contains an outdated or insecure operating system, they have several options:

- Update the operating system (if they have access to it)

- This is often not intended by the manufacturer and, therefore, not part of everyday use. In this case, the operator cannot update the operating system without becoming the (own) manufacturer himself.

- Do not update the operating system

- If the operator uses non-secure products, he is infringing on legal requirements and possibly endangering patients. Therefore, this option is not applicable.

- Ask the manufacturer to update the operating system

- The operator’s only option is to oblige the manufacturer to update the operating system. This assumes that the manufacturer still exists and is willing to carry out this update at a reasonable cost.

- Decommission the product.

- If this is not the case, the operator may conclude that safe operation is no longer possible. In this case, the product must be taken out of service.

Operators are obliged to report safety issues to the authorities. Some operators use this obligation to motivate manufacturers to take action.

5. Conclusion and summary

In many cases, medical device manufacturers are well advised to use commercially available operating systems rather than develop their own.

However, physical medical devices do not have the choice of whether to declare the operating system as SOUP and thus part of the medical device or as part of the runtime environment. Operating systems obtained from third parties are always SOUP for these medical devices. The requirements for operating systems that are only part of the runtime environment are lower.

The focus should always be on specifying the requirements for the operating system very precisely and very specifically for the product and its intended purpose and on ensuring compliance with these requirements during the verification of the operating system. This applies regardless of whether the operating system is a SOUP or developed in-house.

Change History

- 2024-10-23: Article thoroughly revised, restructured, and updated.

- 2016-10-26: The first version of the article was published.