Configuration management is much more than using version management tools like git or svn. This becomes clear when you look at IEC 62304 and the FDA guidance documents.

In this article, you will read about

- what configuration management encompasses,

- which regulatory requirements for configuration management you need to be aware of, and

- which typical configuration management mistakes you should avoid.

1. Configuration management: The fundamentals

a) What configuration management includes

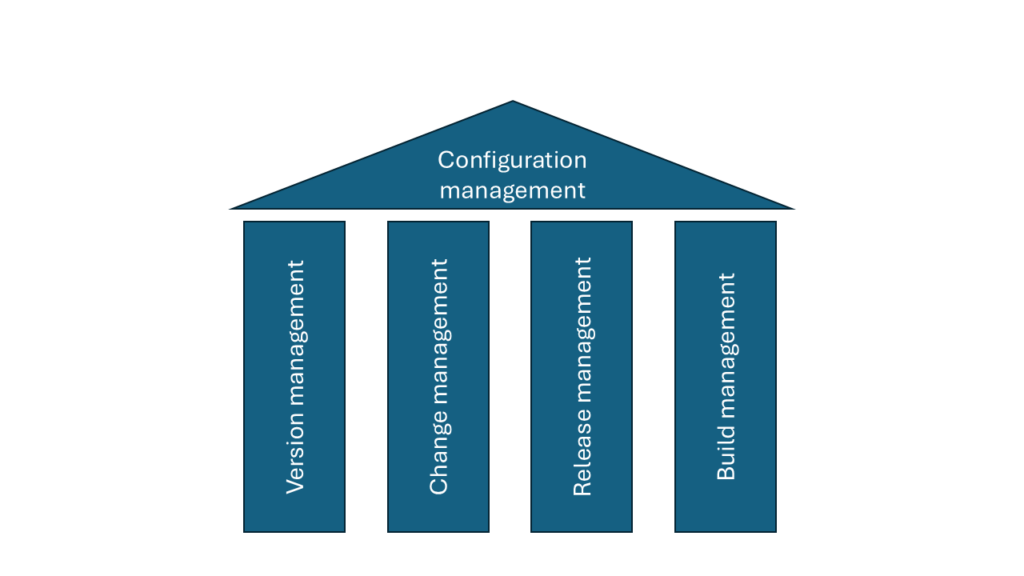

Configuration management goes beyond version management. It is based on four pillars:

- Version management

- Build management

- Change management

- Release management

b) Objectives of configuration management

The objectives of configuration management are:

Controlling, managing, and documenting changes in extensive, complex systems throughout their entire life cycle.

This requires that adjustments, corrections, and extensions be continuously controlled and monitored. The respective system and all its components should always be in a clearly defined state that can be traced back to its origins.

Configuration management is fundamental to a systematic product development process that can be traced anytime.

c) Objectives of configuration management in medical technology

The primary objective of medical device manufacturers is to develop safe products that provide the promised benefits, i.e. that actually fulfill their intended purpose.

These objectives are at risk if manufacturers (especially of software-based medical devices)

- deliver incorrect artifacts (e.g., their own software, third-party libraries),

- mix up artifacts, versions of those artifacts,

- deliver incomplete artifacts,

- have incorrectly assembled the software from the artifacts,

- have forgotten to test and approve a part of the software,

- have inadvertently reintroduced errors that had already been corrected,

- have incorrectly configured products (for a given environment or for a specific customer),

- have overlooked the influence of the development, build, test and production environment on the product, and have not been informed about changes (e.g., at the customer’s site)

- because one employee did something (changed code, requested changes, delivered software) that other employees were unaware of.

The objective of configuration management is to help control this complexity and avoid the above-mentioned errors.

2. Configuration management elements

a) Version management

The version management records and administers the changes to the so-called configuration items. This makes it possible to trace who changed what, when, and why.

Examples of configuration items

- custom source code

- third-party components (SOUP, OTS)

- platforms

- tools

- configuration settings (of products, tools, environments). This also includes build scripts and configuration files.

- media files (images, videos)

- instructions for use

- release notes

The version control system (version management) is the basis for knowing which artifact has become part of which version of the product.

Without a tool, you would have to manage these relationships by hand (for example, in tabular form):

| product version 1 | product version 1.1 | product version 2 | |

| file 1 | file version 3 | file version 3 | file version 3 |

| file 2 | file version 1 | file version 9 | file version 11 |

| file 3 | file version 12 | file version 13 | file version 13 |

Development documents such as requirement specifications, architectures and test reports must also be subject to version control. However, they are usually not part of the delivered product.

Software’s runtime environment and build scripts are also subject to document control but are not part of the product.

b) Build management

Version management alone is insufficient to ensure the product can be reproduced from source artifacts (e.g., source code). The order in which the artifacts are processed (e.g., dependencies resolved, compiled, generated, assembled) can play a role.

Build management aims to build / compile products in a reproducible, complete, and error-free manner.

When dealing with thousands of artifacts and complex “production processes”, companies have little choice but to automate these processes. Tools for build management (here is a list) and tools for continuous integration are state of the art.

The published configurations are the releases, sometimes referred to as versions.

c) Change management (focus: changes to products, not to organizations)

Often, it is environmental requirements that justify changes: bugs need to be fixed, the function is redefined, and a new technical environment requires adjustments. Change management includes documented (!) decisions on whether and how new versions are created in response to such challenges.

Change management’s objective is to control how new and changing system requirements are handled and requests for bug fixes.

Change management includes the process(es) for

- documenting change requests,

- evaluating change requests,

- deciding on measures (e.g., reporting to the authorities, product changes, inaction, training)

- approving changes, and

- monitoring the implementation of changes.

Some companies have established a change control board for evaluating and approving changes.

If this board decides whether or when a change may be implemented and released, it also has authority over release management.

d) Release management

Release management is the process by which software is made available. It determines which configuration changes are included in which version (release) of a product.

The decisions on this are influenced by

- the significance of the change for patient safety,

- laws, e.g., the MDR, which specifies concrete deadlines,

- the urgency of the change from the customer’s point of view,

- availability of persons who can implement the change,

- dependencies of configuration changes on each other.

e) Conclusion

Even though version control systems are the most important and most frequently used type of tool in configuration management, configuration management involves much more than just version management.

3. Regulatory requirements

a) IEC 62304

IEC 62304 (“Medical device software – Software life cycle processes”) explicitly requires configuration management. Its planning must already be part of the development plan. Manufacturers must define

- which artifacts or artifact types are to be subject to version control,

- which activities are necessary in this regard,

- who (in the company) bears the responsibility for this,

- when the artifacts are to be placed under configuration control (necessarily before verification) and

- how is all this to be done during software maintenance and problem-solving.

According to IEC 62304, the software configuration management process includes the aspects mentioned above configuration management:

- Evaluation of changes (→ change management)

- Decision on measures (→ change management)

- Approval of changes (→ change management)

- Configuration history (→ version management)

The standard also requires configuration control for SOUPs, along with verification that the planned changes have been successfully implemented.

b) ISO 13485

ISO 13485 (“Medical devices – Quality management systems – Requirements for regulatory purposes”) does not explicitly require configuration management. However, it does see it as a means of ensuring identifiability and traceability.

c) FDA

The FDA also requires a configuration management plan in the “Software Validation Guidance Document”:

„A configuration management plan should be developed […] Controls are necessary to ensure positive and correct correspondence among all approved versions of the specifications documents, source code, object code, and test suites that comprise a software system. The controls also should ensure accurate identification of, and access to, the currently approved versions.“

d) Further information

Mapping to IEEE 828:2012

A somewhat more comprehensive (and perhaps also more academic) definition of the sub-processes of configuration management is provided by IEEE 828:2012:

- Configuration Identification (CI) → One part is version management

- Configuration Change Control (CCC) → Change management

- Configuration Status Accounting (CSA) →e.g., release reports, DHF, etc.

- Configuration Auditing (CA) → Analytical quality assurance

- Configuration Release Management (CoRM) → This matches the above description 1:1

IEEE 828:2012 and build management

According to the standard, build management extends across CM disciplines. For example, the build scripts must be identified as CI. They are, of course, under CCC, and a record of the versions belonging to a release or currently valid (CSA) is kept.

Changes to build scripts must be checked (CA), and the build script to be used for a release must be available for that release (CoRM).

4. The most common configuration management mistakes

The following problems regularly come to light in audits:

- Not all artifacts are under version control.

- The development and test environment are not under version control.

- Test and product codes cannot be restored for specific points in time and versions.

- The manufacturer has not given any thought to the validation of the tools.

- There is a lack of justification for why requested changes are not implemented.

- There is no explicit change approval.

- Only the latest software version before the release is “checked in”.

- There is no proof that the implemented changes meet the requirements.

- The manufacturer has not tested the delivered version.

5. Conclusion and summary

Configuration management is a prerequisite for professional, state-of-the-art software development. Countless tools automate the steps and avoid errors regularly occurring during manual activities.

However, the tools do not replace a strategy for releasing software in line with market requirements and for quickly and effectively eliminating errors.

Change history:

- 2024-10-17: Headings numbered and added; order in chapters 1 and 4 changed; chapter 5 added

- 2016-08-03: First version of the article published